Tom Cruise and Christopher McQuarrie’s Final Dive: “The Final Reckoning” Writer/Director Takes Us Inside the Submarine Stunt That Caps a Franchise

Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning closes out a behemoth chapter of writer/director Christopher McQuarrie’s career. For over a decade, he’s crafted missions for Ethan Hunt (Tom Cruise) to accept, starting with an uncredited rewrite on Ghost Protocol. He stepped behind the camera for his first film in the franchise as director, the muscular Rogue Nation, which included Cruise holding onto the side of an Airbus A400M as it took off and rose to 5,000 feet, that led to the best bathroom brawl in history in Fallout (oh, and Cruise learning how to fly a helicopter for the film’s insane climatic final battle), the motorcycle launch heard round the world in Dead Reckoning, and now, the gangbusters franchise capper (for now, at least), Final Reckoning.

In this most impossible mission to date, McQuarrie ties the series together in a near-three-hour finale that functions as a proper send-off for the world’s most indefatigable super spy (all respect to James Bond and Jason Bourne) that ties together all of Hunt’s previous missions. It’s a towering, globetrotting experience, but at its core, a simple story: following the events of Dead Reckoning, Hunt and his team must stop a rogue AI, known as The Entity, from unleashing nuclear destruction. In order to save the world one last time, terrible sacrifices will have to be made, and every skeleton in Ethan’s closet will be brought marching out.

As Ethan, Benji (Simon Pegg), Grace (Hayley Atwell), and Paris (Pom Klementieff) journey from one far-off location to the next, the mission becomes as much about saving the world as it is about protecting the people Hunt holds dear. Final Reckoning entertains with character as much as it does with a bravura submarine set piece and dueling airplanes.

McQuarrie spoke with The Credits about honoring the big-screen experience, the evolution of the franchise, and two of the film’s most breathtaking sequences.

You’ve said that if only a hundred people are going to hear your message, it’s not quite worth sharing. What message really drove you on Final Reckoning?

What Tom and I are focused on doing, first and foremost, is getting people to come back to the theater and enjoy that experience and reconnect emotionally with it. Why you and I go to see movies in a movie theater, more than anything, why we keep doing it, and why we look at it as something that deserves to be preserved, is that we have an emotional connection to the act of going to the movies. When I was growing up, that was the only way you saw movies. They didn’t come out on home video for much, much longer. In fact, when I was much younger, there wasn’t even a home video. Sometimes you’d have to wait years before you would see a movie on television again. Now the release window is so small, and a younger generation doesn’t care where they get the movie from.

And it’s certainly not because people no longer enjoy going to the movies…

It’s not that they don’t like movies – they just don’t need to go to the theater to see them. They don’t feel that same emotional connection to it. It’s very understandable given the fact that theaters are maintained the way that they are, and people behave the way that they do in movie theaters. You have to overcome all of that. You have to make a movie that’s so much bigger than that, that people are willing to brave it to come. That’s what Tom and I are reaching for and looking to preserve, and you have to make it an emotional experience, and you have to make it an experience that is specific to the big screen.

It’s hard not to look at almost 30 years of this franchise and think, what does Final Reckoning say? What does this entry, which is about defeating AI and protecting your crew, say about Tom Cruise?

That’s an inevitable part of making a Mission: Impossible. I recently came across a quote that suggests every movie is a documentary about itself. The making of Mission: Impossible is not too dissimilar to watching a Mission: Impossible. The story in the movie becomes the story on set, and vice versa. It’s not like I’m making an overt statement about those things. It just becomes self-evident in the making of it. I mean, look, Tom Cruise as an actor is somebody that people have been looking at for 40 years, and people have been making a great deal of assumptions about. And in just the same way I’m using what I sense to be an emotional moment in the zeitgeist, I’m also using people’s suppositions about Tom and playing against them.

How so?

I knew that when people came to Top Gun: Maverick, they would naturally assume that the story we were telling about this character would have similarities to Tom. People would draw those parallels and think that that’s what we were saying the movie was about. No one’s ever guessed what I was really after. Nobody’s ever put their finger on it, and it doesn’t matter to me that they do. It matters that everybody came to the movie.

Can I ask, what were you after?

You can certainly ask.

And would you answer?

That would take away the movie’s mystique. If anybody should ever guess it, I would tell them. However, right after Maverick, and before the film was released, I knew we had a successful movie, as it had been on the shelf for quite a long time during the pandemic. Tom and I always talk about how one of the hardest things to do in this business is to repeat a successful action. People tend to attribute success to luck and take those successes for granted, rather than analyzing why they work. Everything you’re looking at in these movies is what we have learned from the previous movie, and applying it.

For example?

There were things we tried in Dead Reckoning that worked, things we tried in Dead Reckoning that didn’t. We applied those lessons to Final Reckoning, but we also didn’t play it safe. We continued to push. I know there are decisions in this movie that not everybody necessarily agrees with, and I just urge anybody who didn’t fully take it in the first time to go and see it again. Everybody I’ve talked to who has seen it a second time has a completely different reaction to it.

It’s a lot of movie.

It’s a lot of movie, and it’s a lot of setup, which, for a lot of people, they’re looking to get to what they come to believe Mission is about. Tom and I have very different impressions about what Mission is about. The things that you come to expect are what you come to expect, but to Tom and me, that’s not what Mission is about. And so, for me, I find the setup, the character drama, and all that interaction to be quite compelling. Not everybody does.

Each Mission has its own flavor, which is why the franchise is so entertaining. How’d you want your installments to continue to evolve stylistically?

And it has to. I appreciate the love that fans of the franchise have for all the other movies. Sometimes you feel people who have their favorite Mission and they want that Mission again, but that’s entirely not the point of Mission. As someone who’s directed four of these movies, there are three rules of Mission: Rule number one is you’ve got to have the theme. Rule number two is you have to have a mask gag. And rule number three is he’s got to get a mission: “Good evening, Mr…” Those are the only things Tom Cruise really poses in the movie. That’s the formula of Mission: Impossible.

The other thing that I took to heart: I listened very intently to people’s dialogue about the movie. They want a different director every time. And so, I endeavor to do that with each one, even these last two, which were presented as two parts of the same story. I’m a very different director on Final Reckoning than I was on Dead Reckoning, and a very different director on Fallout, and on Rogue Nation. That was to keep that feeling alive, that feeling of evolution and variety in all of these movies. And you look no further than the example of Simon Pegg.

How does Benji represent the franchise’s evolution?

On Ghost Protocol, when I came in and kind of blew up the script, Simon felt a lot of the stuff he had signed on for was disappearing. They were things that would never have made it to the final film, and I understood what would and what could. And so, when Simon was upset because he was losing a mask gag, I asked, “Why do you like the Mask gag?” He said, “Because I don’t want to just be the guy behind the computer. I want to get my hands dirty and do some spy stuff.” And I said, “If I can give you something other than the mask gag, as good or better, as long as it’s team-oriented, would you be fine with that?” Simon said, “Yeah, I don’t really care what it is, just something not by the computer.”

I ultimately engineered the story so that Simon was the guy who saves Brandt’s (Jeremy Renner) life and kills the second villain in the movie, all of which are things that would never have happened in the movie they were engineering. It was just not Benji’s destiny. It took some doing, some salesmanship on my part, to get it there.

And that began an agreement between Simon Pegg and me that Benji would always evolve. He had to stay Benji. He is the beating heart of the team, and he’s a fun character, but we wanted Benji to grow and to evolve. In each installment, we push it further. And in the editorial, we pull back a bit, exploring and giving ourselves those options. You feel Benji evolve chapter over chapter, until this one, where he’s ascended to a completely different level. And I see the franchise in much the same way. For me, it had to evolve. If I were going to continue to be the director of these movies, it had to evolve.

Two of this chapter’s defining traits – fear and silence – may be best exemplified by the submarine sequence. How did you and your crew nail the pace of that exciting dread?

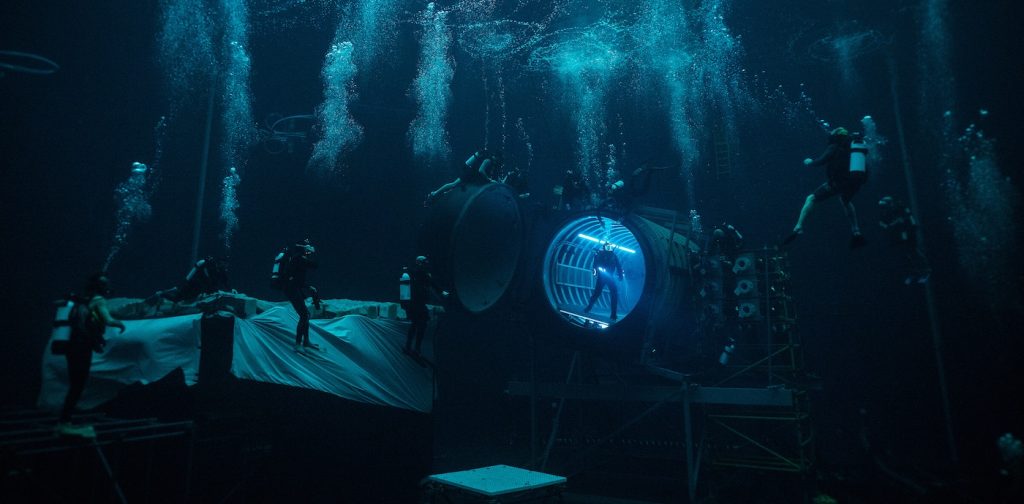

The pace is dictated by the gimbal. To understand what the gimbal was – imagine a cylinder, a 60-foot-diameter steel latticework cylinder that weighed a thousand tons. Into that, you could load the set – the submarine set. They were interchangeable, so every room that you see Tom move through is a room that had to be loaded and unloaded from this gimbal, which rotates 360 degrees, tilts 45 degrees in both directions, and is fully submersible in an 8.5-million-liter tank – all of which was scratch-built.

How much experimentation was involved in operating the gimbal?

We didn’t really know what this thing was going to do until we turned it on. We knew how fast it could turn. And so, we did a bunch of animatics with the submarine rotating and did a great deal of experimentation in terms of putting in the hypothetical camera placements and seeing what happened if it was half-filled with water, all full of water, only 20% full of water – to see what those cameras could see. And it became pretty clear, even before the gimbal was finished, that the gimbal’s slow rotation was not a bug – it was a feature. The scene just has a certain torturous, unrelenting, inevitable sense that he’s trapped in a giant gear.

How did the mobility and weight of the dive suit, as well, influence the pace of that stunt?

A Mark VII dive suit, when it’s wet and he’s not submerged, weighs close to 125 pounds. He’s carrying close to his full body weight while he’s climbing around inside that submarine, which we knew would be slow and agonizing. Well, let’s just lean into that. Let’s not fight it. Let’s make this environment just glue, and it just won’t let him go. And that’s what I think you’re feeling when you’re watching that scene.

As Anthony Hopkins says in Mission: Impossible II, “This is not mission difficult, it’s mission impossible.” How do you approach escalation and write the impossible within an action sequence?

The essence of action is suspense, and the essence of suspense is not creating a scenario that can’t possibly end well. That’s not the challenge. The audience knows how a scene is going to turn out. They know how a movie is going to turn out from the first 10 minutes of the movie. The first 10 minutes are a contract between the filmmaker and the audience that says, “This is the kind of movie you’re getting.”

So I don’t try to create a scenario where the audience can’t imagine the outcome, because I know they’re always imagining the outcome, whether they’re right or not. What I’m trying to do is create a situation where the audience believes it will end well. They need it to end well for the movie to continue, but what they can’t see is how it possibly could end well. You’re just constantly creating scenarios where you’re saying, “There’s no believable way out of this,” and then finding your way out.

Erik [Jendresen, screenwriter] and I started with the ending. We knew how it was going to end. We just had to engineer our way backward from that. And we also knew you, having seen the sequence, know how it ultimately ends. We’re telling you the whole time, “This is what’s going to happen,” and the audience is thinking, “No, that won’t happen.” And, well, it does.

Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning is in theaters now.

Featured image: Tom Cruise and Director Christopher McQuarrie on the set of Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning from Paramount Pictures and Skydance.