“Winning Time” Cinematographer Todd Banhazl on Capturing the Flow State

Winning Time: The Rise of the Lakers Dynasty sounded, on paper, like a no-brainer for HBO. Based on Jeff Pearlman’s book “Showtime: Magic, Kareem, Riley, and Los Angeles Lakers Dynasty of the 1980s,” the source material had every ingredient you’d want for a prestige series. It had larger-than-life figures in Magic Johnson and Kareem Abdul Jabbar (as well as their foils and foes around the NBA), it’s set largely in Los Angeles in the late 70s and early 80s (gaudy, glitzy, debaucherous—catnip for TV), and, it had a genuinely compelling story to tell about not only these iconic individuals but about the remaking of the NBA.

It’s when you start to unpack what Winning Time‘s cast and crew were undertaking do you begin to appreciate the challenges. Obviously difficult things, like recreating seminal moments that are a part of NBA history (like Magic’s epic game 6 against the Philadelphia 76ers in the 1980 Finals), would require technical expertise. But then there were smaller but no less daunting challenges, from reconciling the height differences between the actors and the NBA legends they’re portraying (and their fellow co-stars), working in a variety of formats to mimic the look and feel of the era, and re-creating iconic locations like the LA Forum, Boston Garden, and Philadelphia Spectrum. And all of this is arguably secondary to the main task of capturing moving performances—including a phenomenal Quincy Isaiah as Magic and Solomon Hughes as Kareem— that could withstand the inherent scrutiny of watching people portray icons who are not only alive and well, but still very much a part of the public conversation and consciousness.

Stepping up to this challenge was cinematographer Todd Banhazl, who spoke to us about taking on a project that was as joyous as it was difficult, and what it took to bring it all together (hint: a camera operator on rollerblades).

Walk me through the process of capturing some of the iconic moments on the court, including Magic’s incredible game 6 performance in the NBA finals against the 76ers.

The idea behind Game 6 was to see Magic thrive in every position. We wanted the camera to match the balletic superhuman flow state that Magic entered in that game. We used many tools such as cranes, a camera rigged to a broom-type device, Steadicam, and the Ikegami vintage TV cameras of course; but, our most effective tool turned out to be our Rollerblade Operator John Lyke. We gave John a small 16mm camera and a backpack rig, and we rehearsed him into the plays. He became another player on the court, in essence. Finally, we were able to keep up with the pace of Showtime Era basketball while keeping the camera physically close to the players and inhabiting their emotional state.

There are more varied looks on this show, some of them mimicking the camera technology from back then—how did you achieve that?

From the beginning conversations between Adam Mckay and myself, we both knew the show needed to be shot on real film, and we were both excited by the idea of mixing formats. The scripts have a kaleidoscopic quality and we wanted that reflected in the images. After a lot of testing we landed on an aged Ektachrome 35mm look being our main format, and mixing into that documentary style 8mm and vintage video tube cameras from 1980. The idea was to create a collage of American cultural memory.

If we did our job right the audience should lose track of what we shot and was actual archival from the period. It felt like using the actual formats that were used in the 60s, 70s, and 80s, was the most joyful and effective way to achieve this. When we had to use more modern film stocks, we did various photochemical and digital techniques to age and destroy the film so that it would feel like an old film print found in a dusty box labeled “Lakers 1980 footage.” For example, we asked the film lab to leave all the dust and hairs on the negative. Things that are normally cleaned up we fought to make sure stayed in the image. Those beautiful imperfections are what excited us the most.

The series breaks the fourth wall with characters, especially John C. Reilly’s Jerry Buss, talking directly to the camera. How did you approach filming those confessional moments?

I always thought of those fourth wall moments as something like Wayne’s World or Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, or, like The Brady Bunch, but with cursing. All of those moments are in the script. We found that monologues worked best when you designed a special shot for the character, but all the quick asides felt best when you did not create a special moment for them, instead, we asked the actors to steal each other’s shots. Someone could look over their own shoulder and steal someone else’s medium shot, to throw in a quick fourth wall break.

So much planning went into this series that most people wouldn’t even think of, including having to mimic the height of the players, like the seven-foot-tall Kareem and the 6’9” Magic—how did you create angles and environments that made the actors appear that tall?

This was one of our biggest challenges. I remember our showrunner Max [Borenstein] said to us, “They made Gandoff 10 feet tall, we have to do the same here for our characters.” It was never one technique, it was a combination of all the tools that sold the illusion. Smaller pieces of furniture or lower door frames were built into the sets. Apple box highways, forced perspective, and lower angles. Putting our cast near shorter extras. Body doubles. Height shoes. Every trick in the book. It becomes even more complicated when the actor’s heights need to look accurate in comparison to each other. I’ve never had more difficulty shooting a simple wide shot!

How did you approach lighting the very disparate environments in the show, from sunny Los Angeles to Lansing, Michigan, where Magic is from, from iconic places like the Garden in Boston and the Spectrum in Philly?

The general idea was that LA would feel sunny and like the future. That bling would at first be intoxicating and then over time feel more like a drug, something our characters are addicted to. Lansing would feel colder, snowier, but have a softer more family feeling, more like “back home.” It might not be as glamorous as LA, but there is comfort in family and in a world that isn’t obsessed with fame and money.

Each Arena had its own color and light design. The LA forum was the most spotlit, like a rock-and-roll show. The Philly Spectrum had a cooler, more east coast metal halide stadium look, and the Boston Garden was what we called ‘piss yellow’ and was left intentionally very warm, ugly, uncorrected, and gross. It was a lot of fun creating the different looks.

What kind of conversations did you have with Adam McKay, Max Borenstein, and Jim Hecht about the overall look they were going for?

We knew the show wanted to have a visual bravado and maximalist approach. Loud. Everything and the kitchen sink. It seemed like the best way to match the bravado and pizazz of the showtime-era Lakers. We also wanted to be able to experience our characters as mythic, larger-than-life cultural icons, and at the same time be able to see them as vulnerable flawed human beings. The mixing of formats allowed the visual style to play a thematic role in this, along with the writing and the performances.

Was there a particular sequence or location you found most challenging?

Everything about this show was ambitious, larger-than-life, and difficult. But that was the joy of it. If I had to pick something, I would say chasing the famous heights of the basketball players was a massive undertaking.

With season 2 confirmed, what lessons did you learn that you’ll carry with you, and what, if anything, might you do differently going forward?

I’m excited to push the style even further, and dig into even deeper emotional territory with our cast and scripts. It’s really fun to have such wild paintbrushes to choose from when shooting a show. It’s also really exciting to quiet down and just photograph those brilliant actors doing their finest work when the time is right.

For more on Winning Time: The Rise of the Lakers Dynasty, check out these stories:

“Winning Time” Co-Creator Jim Hecht on His Love Letter to the Lakers

“Winning Time” Costume Designer Emma Potter on Making Magic With the Lakers

“Winning Time” Writer Rodney Barnes on Scripting HBO’s Fast-Breaking Lakers Series

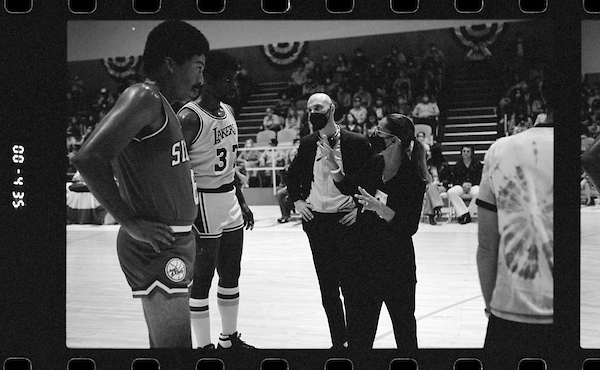

Featured image: Solomon Hughes & DP Todd Banhazl on the set of “Winning Time.” BTS. (Warrick Page/HBO)