Caged Dynamics: How DP Ula Pontikos Frames Willem Dafoe & Corey Hawkins in “The Man in My Basement”

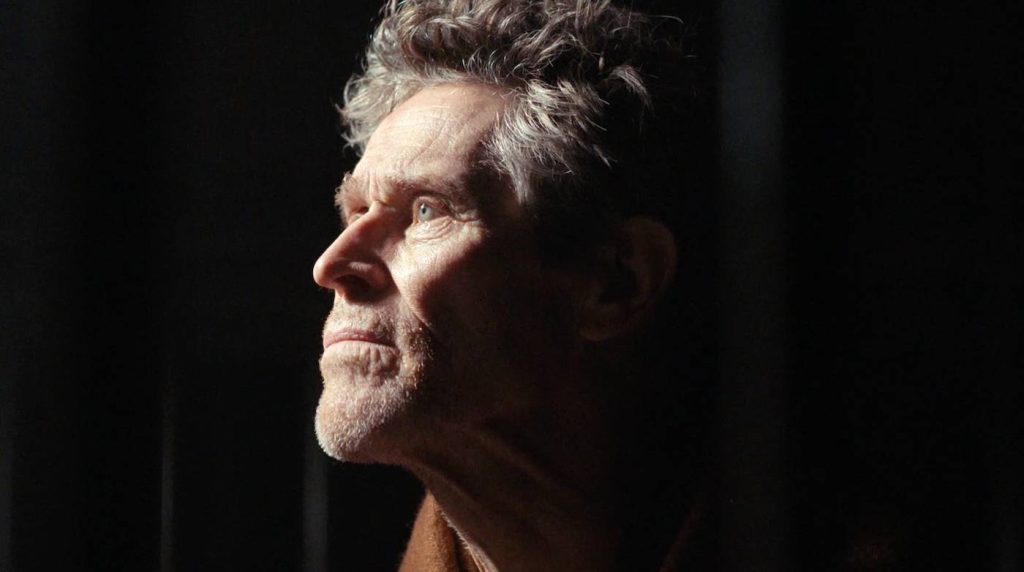

The Man in My Basement marks Nadia Latif’s feature directing debut, and it’s a doozy. Latif adapted author Walter Mosely’s acclaimed 2004 novel of the same name, from a script she co-wrote with Mosely. The film is set in the quiet village of Sag Harbor, New York, where Charles Blakely (Corey Hawkins) is a man adrift until he gets a strange offer from an even stranger businessman, Anniston Bennet (Willem Dafoe), to rent out his basement. What seems like a saving grace quickly turns south when Charles finds his new house guest has locked himself in a metal cage. Kinky? Hardly. What plays out is a psychological thriller steeped in weighty themes – race, colonization, preservation, power, self-reproach – as the two try to understand each other better, the situation, and, for Charles, why the hell this is all happening to him.

For Polish cinematographer Ula Pontikos (Russian Doll), it meant creating a striking visual language that supported the simmering animosity of the characters through light and shadow, camera angle, and shifting eye lines to guide the audience through changing power dynamics. In designing the movement, Pontikos tells The Credits, “Most of our discussions kept coming back to one thing: What’s the intention behind each frame? What feeling are we going for in each moment? Who does the audience need to be with at any given time? Are we seeing this through Charles’s eyes, or are we observing him? That intention was everything. And most importantly, when do we get inside the cage and observe Charles from within? Every shot was a storytelling decision.”

Did you reference any material to create the dynamics between Charles and Anniston?

Nadia’s a huge fan of Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep, and that definitely shaped how we approached our character, Charles—that raw, intimate feel with gentle coverage. We even shot a scene with a girl in a dog mask as a direct homage to Burnett’s film. We were also watching the film Chameleon Street by Wendell B. Harris Jr, and films from Ousmane Sembène, Djibril Diop Mambéty, and Med Hondo. There’s a parable-like quality to all those men’s films, which Nadia used as a reference and a big introduction for me to West African Cinema.

How about defining any visual themes to support the story?

For Nadia and me, this is fundamentally a story told through a multitude of two-shots. The entire film is woven together with these pairings – sometimes romantic, sometimes antagonistic, and sometimes moments of raw connection. Each two-shot was carefully considered: how we framed it, what the lighting conveyed, what color subtly signaled about the characters’ relationship in that moment. Even the use of split diopters became a deliberate device to visually articulate the shifting power dynamic between Charles and Anniston, keeping them both in focus but emotionally worlds apart.

Most interactions between Charles and Anniston take place in Charles’s basement. How did you treat the evolving camera language?

Visually, it was interesting to explore artists like Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, whose work both Nadia and I bonded over. The way she not only paints from imagination but also paints the figures against these dark, muted backgrounds. But our biggest reference point was The Silence of the Lambs. We had long talks about how to frame the dynamic between two people when one is almost completely stationary. A lot of it came down to how we reveal the cage — we were super conscious about holding back just enough to make it feel powerful when you finally see it.

We also looked at the controlled chaos in Zulawski’s Possession for inspiration on visualizing a total psychological breakdown, especially the way the camera moves, almost like its own character with intention. The steadicam in that film doesn’t just follow the action—it reveals story points on its own terms.

How did you want to reveal Charles seeing Anniston in the cage for the first time?

So, in that first shot where Charles comes down into the basement, we stay with him – really sit with his expression – and only then do we reveal that Anniston is already in the cage. That said, it was never about recreating a specific shot directly. Our focus remained on what each scene fundamentally needed to feel true. While Nadia shared a list of about twenty films that inspired the overall tone and mood of the project, our on-set conversations were less about replicating those references and more about uncovering the emotional authenticity of Charles’s journey. Those films were a compass, not a map.

You mentioned using the split diopter, which brings two subjects at different distances into focus. Films like Jaws, Pulp Fiction, and Mission Impossible have famously used it. What was the thought process behind this use?

These shots weren’t just stylistic choices; they were emotional statements to us. We used two split diopter shots in the film, and I believe they were to make an important power dynamic point. Like so much of our approach, it comes back to how you convey a story through two-shot frames. In a single frame, the split diopter visually articulates the power dynamic between Anniston and Charles: Charles appears small and vulnerable, almost receding into the background, while Anniston feels overwhelmingly present and oppressive, whilst keeping them both in focus, giving equal importance to them. Throughout the making of the film, we were asking ourselves: What feeling are we trying to evoke between these two characters? How does framing affect perception of power?

There’s a moment where Charles turns off the lights on Anniston. “Tonight you’re the prisoner and I am the motherfucking warden,” he says. It’s followed by several sequences of them questioning each other, where there’s a tonal shift in lighting. What went into that language?

That scene marks the dramatic lighting shift in the film. Charles is struggling to reclaim control, while Anniston is desperately begging him to stop. My initial approach for the basement was straightforward – a simple, diffused tungsten bulb to maintain a raw feel. But for this pivotal moment, when Anniston begs him to leave the light on, I swapped the bulb for a harsh, underused photo flood bulb. Its aggressive, powerful glare is intentionally uncomfortable. It strips away any warmth or subtlety, visually amplifying his panic and helplessness. The light itself becomes a manifestation of his state of mind: exposed, merciless, and utterly hopeless.

Later, Anniston has a breaking point, telling Charles, “I don’t want to play anymore.” The dramatic scene starts, only lit by a flashlight. How was that pulled off?

The color, intensity, and quality of the light were very important. We tested numerous torches to find just the right hue and brightness. To augment the single-source setup, I positioned a polyboard just off-camera to bounce enough light back onto Charles’s face. Sometimes, you’d find me or Willem himself holding that board to keep the exposure back on Charles’s face to get a return of the single source light. But a little extra came when Willem suggested moving the torch itself during the moment Anniston grabs Charles. That subtle motion – the light shaking, flickering, becoming nervous – didn’t just illuminate the scene; it added great tension to the scene.

The Man in My Basement is in select theaters now before arriving on Disney+ and Hulu September 26.

Featured image: Willem Dafoe and Corey Hawkins in “The Man in My Basement.” Courtesy Hulu.