“Winning Time” Showrunner Max Borenstein on Crafting an American Epic

Before Winning Time: The Rise of the Lakers Dynasty showrunner Max Borenstein sat down to write the show’s pilot episode, executive producer Adam McKay gave him one simple note: “Have fun with it.” Crammed with boisterous performances, Winning Time (its season finale aired this past Sunday, May 8, and is now renewed by HBO for a second season) does offer fun to spare but the series also brims with drama as it chronicles the betrayals, rivalries, romances, traumatic childhoods, family infighting, and near-death traffic accidents leading to the Los Angeles Lakers’ 1980 world championship.

Borenstein previously wrote four Godzilla movies and Worth, about the real-life lawyer who ran the 9/11 Victim Compensation Fund. He’d also worked on a couple of projects for HBO that never saw the light of day. When McKay and producing partner Kevin Messick approached the network with their idea to adapt Jeff Pearlman’s book “Showtime: Magic, Kareem, Riley, and the Los Angeles Lakers Dynasty of the 1980s,” HBO executives introduced the Oscar-nominated director (Don’t Look Up, The Big Short) to Borenstein and they clicked.

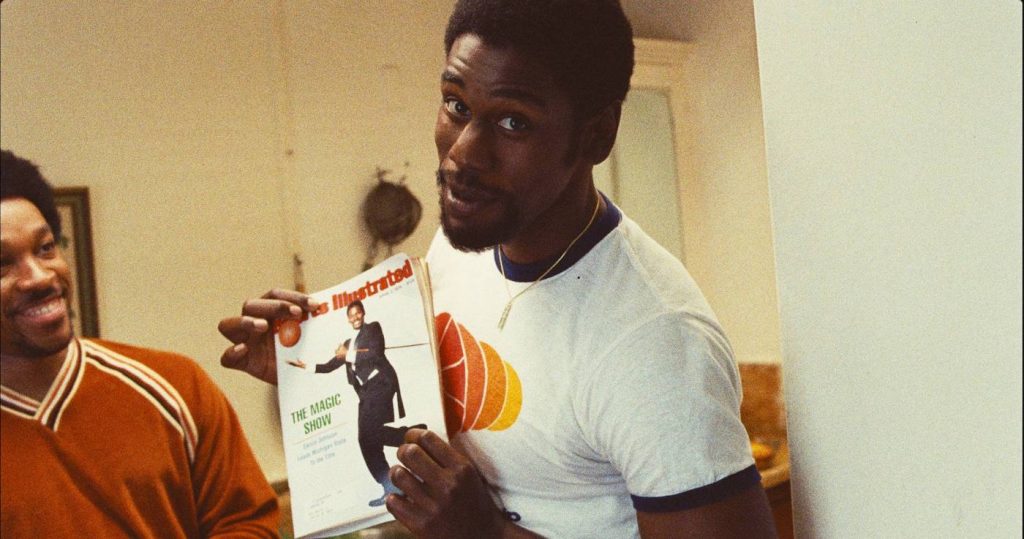

Borenstein and his writers’ room crafted an intricately detailed narrative that attracted Oscar winners Adrian Brody and Sally Fields along with Pulitzer Prize-winning actor Tracy Letts, Jason Clarke as hot-tempered coach Jerry West and John C. Reilly in the lead role of team owner Jerry Buss. The show also showcases uncannily effective star turns from newcomers Solomon Hughes as somber Kareem Abdul Jabar and Quincy Isaiah as the joyous Magic Johnson.

Backed by a couple of basketballs perched on the bookshelf of his Los Angeles office, Borenstein spoke to The Credits about combovers, skyhooks, obsolete cameras, former Jerry West’s criticism of the show, athletes as artists, and basketball as a vehicle for addressing race relations, capitalism and gender roles.

What drew you to this story?

I grew up in L.A. and the Lakers are the first team I knew as a child, but I wouldn’t have wanted to make a show that was just for basketball fans. What really attracted me about the Lakers’ story is that we could dive deep into the specificity of this world of basketball and use that as a prism to reflect central themes of what America was becoming in this seventies-to-eighties moment that created the “Me Generation,” which I think is now, for better the worse, the foundational core of where we are today.

The show personifies all these big themes through an array of wildly ambitious characters who carry around some bittersweet backstories.

The moment I stopped looking at the characters as athletes and started to see them as artists, that’s when I started to connect. There’s something driving these people to fill some kind of hole that might never get filled. That’s where the fire, the drive comes from. There’s some kind of wound, and I feel like there’s a beautiful pathos in that.

Winning Time seems like a beast of a show to put together: ten episodes, period piece, huge cast, fact-based. HBO greenlit the series in April 2019. Where did you go from there?

We were about to shoot the series when the Pandemic hit so my collaborators and I just kept re-working the scripts for a year [during lockdown]. This pause allowed us to find aspects of the story where normally we would have had the big train [of production] on our asses. Now we had a year to do more research and find and identify the different ways they coach and their personalities.

Speaking of coaches, Winning Time prompted intense criticism from Jerry West and Kareem Abdul Jabar over the way Coach West was portrayed. Were you surprised by their reactions?

I can’t imagine how strange it would be to have my own life adapted and dramatized as a television series so I would never judge anyone’s reaction. What I can say is that the show was made with a great deal of affection and appreciation and respect for all of these people. It’s also been made with a great deal of research. We read every book we could get our hands on. We watched every interview, and read every article from every daily newspaper using the Lexus Nexus [database]. And also, one great benefit of telling a story about people who live their lives in the public eye is that they themselves have told their own stories in their own words, which is what Jerry West did in his wonderful book “West by West: My Charmed and Tormented Life.”

Wait a minute, Jerry West’s memoir has “Tormented” right there in the title?

Yeah. It’s a magnificent book and a big source for us, as were many other books.

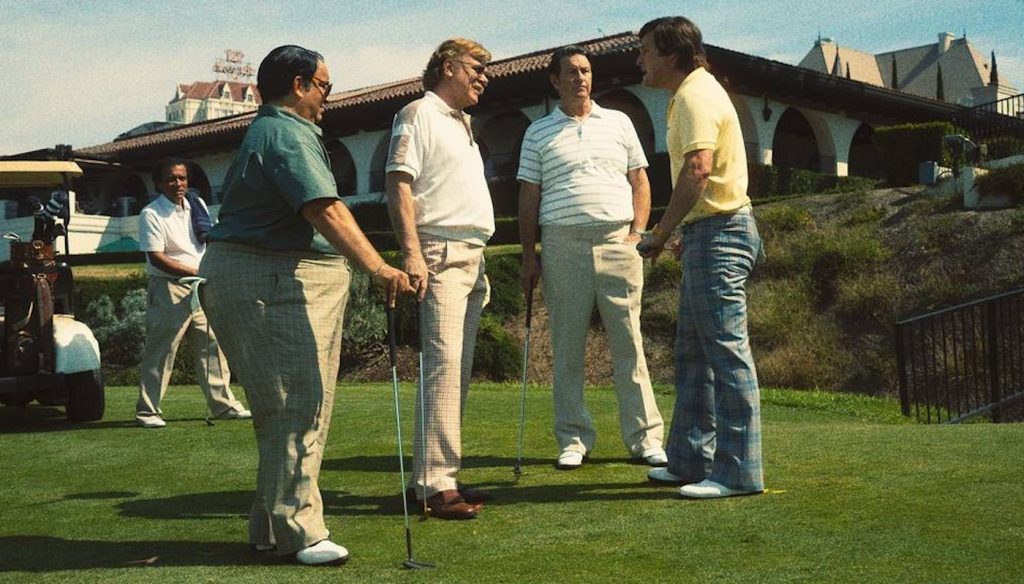

I haven’t read the book, but it’s startling to see Jerry West breaking a golf club over his knee in the first episode, throwing his MVP trophy through the glass window of his office, and later, curled up in his underwear on the floor of his home.

Our guiding star throughout the process was making sure that our characterizations and the big facts were true to form. That said, of course, it’s a dramatization. We’re getting into closed rooms and behind doors that we have no access to. We can only do our best to piece together and dramatize what may have been said, what plausibly could have been said, based on our understanding [of the facts]. That’s part of the art of it, the challenge and the joy of doing a dramatization. It’s all about making choices.

Casting Winning Time must have been a gargantuan task. First of all, it’s a huge ensemble. Second, many of your cast members not only have to act; they also have to be really tall. Quincy Isaiah does a remarkable job in channeling the Magic Johnson mystique. How did you find him?

Quincy had just arrived in L.A. He’d been a center for his football team in Kalamazoo but wanted to be an actor. He sent a tape to our genius casting director Francine Maisler just as McKay and I were starting to get nervous. We’d looked at dozens of people, but no one brought the kind of charisma we needed. Then Francine said, “Look at this tape. We watched it in McKay’s office. There was something about Isaiah’s smile, his charm. We brought Isaiah in, gave him a couple of scenes to read and he blew us away. Then we asked, can you play basketball? Of course, he said yes – – he’s an actor! And Quincy actually could play, a little. So we had our friend Rick Fox put Quincy through the wringer. Rick came into the gym determined to make Quincy puke, and Quincy was determined not to give in. He just gutted it out. Every time he did a scene with one of the greats, whether it be Jason Clarke or John C. Reilly or whomever, Quincy took it as a challenge to bring it. He’s been a joy to watch.

Winning Time breaks the fourth wall in ways made famous by Adam McKay in The Big Short. You’ve got direct address bits where John C. Reilly as Jerry Buss speaks straight into the camera, and you’ve got giant on-screen text describing a freeze-frame of Jason Clarke’s Jerry West, for example, as “NEVER BEEN HAPPY.” Did you take naturally to this irreverent style?

I wrote the pilot knowing Adam’s style, which I think of as less a style as it is a freedom. When he directed the pilot, it kind of unshackled everyone to explore and experiment and take risks. There’s a flexibility to pull out whatever tool you feel will help tell the story best. Hank Corwin, who edited the pilot, has an incredibly free-wheeling style, intercutting different footage that aesthetically short circuits the wall you put up when you’re watching something you know is fictionalized.

The grainy video look goes a long way toward evoking this early eighties era. How did you create that vintage effect?

That came from our boy wonder genius director of photography Todd Banhazl. He found this defunct format Ikegami camera that hadn’t been used in forty years when it was replaced by Beta[max]. So he dug up these old Ikegami cameras, refurbished them, and initially used them to replicate game footage or news footage. But it quickly became clear to us that whenever we saw a scene shot by the Ikegami on the monitor, it felt like a time machine. What I continued to find throughout the season is that the Ikegami [footage] feels like someone’s taking a home movie of the scene. Rather than putting you at a distance, it pulls you into the emotion in a kind of shocking way.

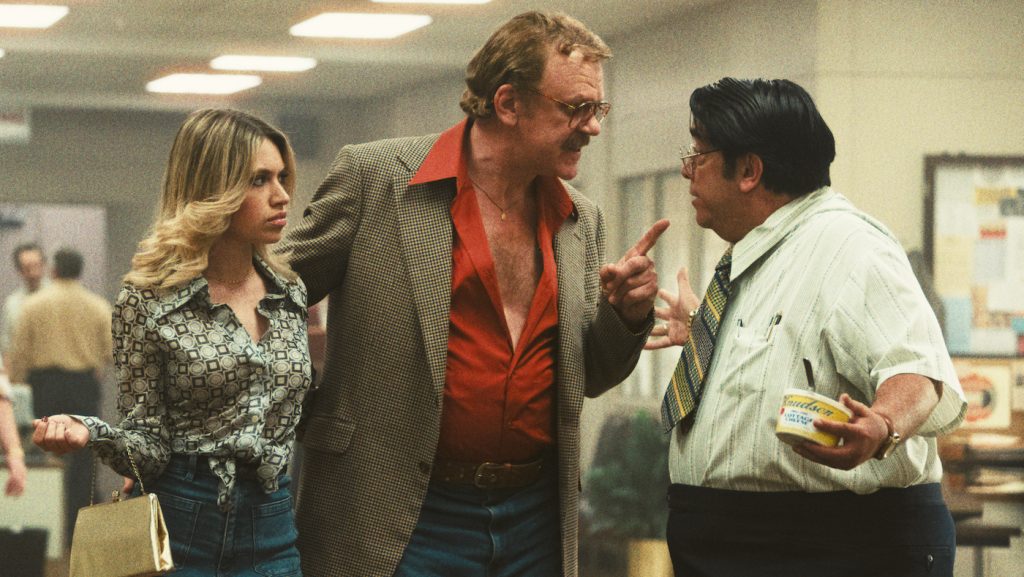

Also kind of shocking is John C. Reilly’s portrayal of Jerry Buss, the brash real estate hedonist whose vision of basketball as entertainment helped revitalize the NBA. Watching Reilly as Buss in his combover, shirt unbuttoned to his waist, the aviator glasses, the mustache, the drinking, the cocaine, the smoking, the Playboy Club: He’s a real piece of work.

That scene where we see Jerry doing the combover is the perfect metaphor for this Gatsby-like American character that John embodies so well. He’s irrepressible. You can’t keep him down. If you say, “Well you’re bald,” Jerry says, “No I can overcome that too!”

Casting John C. Reilly in this juicy role produced its fair share of controversy, fair to say?

Everyone knows the ins and outs that have been reported [about Adam McKay alienating his one-time best friend Will Ferrell by not picking him to portray Jerry Buss]. A week or so before production, John’s name came up and it was obvious that he would be genius in the role. We went over to his house and saw him with the combover and the mustache. John had already started to vibe that character in ways that made the hairs on the back of my neck stand up. The moment you see him as Jerry Buss, you say “How could it have been anybody but John C. Reilly?”

There’s so much drama happening off the court in Winning Time but it’s the basketball games that provide the throughline for this story about the Laker’s 1980 championship season. How did you go about re-creating these games?

Getting the basketball right was a huge challenge. People can watch real games on YouTube, so our goal was to get inside the emotional world of the men playing the game. To do this, we studied game footage, not always with an eye to a perfect reproduction of exact moments, but with the intent of capturing the style of these particular players. Magic had to have his dribbles and passes right. Wilkes had to shoot like Wilkes. Kareem had to have his skyhook down pat. Our basketball coordinator Idan Ravin, who works as a shooting coach with a number of high-level pros, was instrumental in training the actors and bringing this vintage style of the game to life.

Did you have access to the actual arenas from this era?

Because of Covid, we couldn’t shoot in real arenas so we built our own professional basketball court and stands on a sound stage. Combined with incredible VFX work, it created the illusion of all these bygone arenas.

Anything else you’d like to add about the making of Winning Time?

We think of it as an American epic that presents this cross-section of Americans, wealthy, poor, Black, white. We’re dealing with capitalism, racism, race relations, and gender roles while still maintaining a certain lightness of touch. It’s fun and there’s a weight to it.

For more on Winning Time, check out these stories:

“Winning Time” Co-Creator Jim Hecht on His Love Letter to the Lakers

“Winning Time” Costume Designer Emma Potter on Making Magic With the Lakers

“Winning Time” Writer Rodney Barnes on Scripting HBO’s Fast-Breaking Lakers Series

Featured image: Solomon Hughes, Quincy Isaiah. Photograph by Warrick Page/HBO