“Marty Supreme” Composer Daniel Lopatin on Blending Synths & Orchestra for Timothée Chalamet’s Ultra Ambitious Striver

Oscar-shortlisted composer Daniel Lopatin earned a reputation amongst electronic music fans for his steady stream of experimental solo albums recorded under the name OneOhTrix Point Never. But it’s Lopatin’s pulsating score for Marty Supreme that will surely expose his synth-driven compositions to a broader audience.

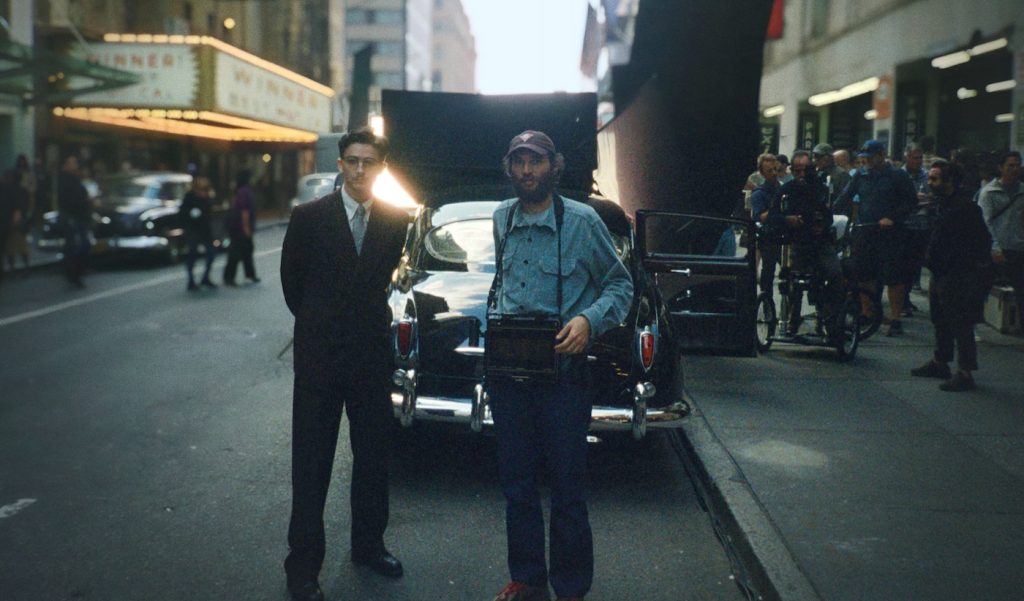

Filmed in New York City and set in 1952, writer-director Josh Safdie’s fact-based movie stars Timothée Chalamet as ping-pong hustler Marty Mauser, who’s hell-bent on achieving fame and fortune against all odds. Lopatin previously scored Uncut Gems and Good Times, both directed by Josh and his brother Benny. This time around, Lopatin sounds especially psyched about his collaboration with Josh Safdie. “As an artist, you’re signing up for this weird thing, which is ‘What’s your point of view?’ You need to spend a lot of time refining it. To then fuse your point of view with somebody else’s, that could be a recipe for disaster. Or, the way it turned out with Josh and me, it turned out pretty incredible, seeing him reach the zenith with Marty Supreme.”

Speaking from his home somewhere in the New York-New Jersey-Connecticut Tri-State Area, Lopatin breaks down his pulsating blend of electronic and acoustic sounds, explains how he cranked up the intensity for the film’s European recording sessions, and describes the “adversarial” challenges of brainstorming music ideas with Safdie in a windowless Manhattan cubicle nicknamed The Fishbowl.

One of the exciting things about your Marty Supreme score is the way you blend synthesizer elements with acoustic instruments and human voices. Can you talk about the musical language you put together for this film that takes place mainly in 1952?

I see Marty Mauser as a hot knife slicing through the old world, and he’s the new world. He’s the future. Marty is the Fairlight [synthesizer] and the world is the orchestra and the choir. They’re like this labyrinth of rules and regulations and stodgy people telling you that you’re not gonna amount to sh**, stay in your lane, you’d be a perfectly great shoe salesman, and all that kind of stuff. It’s the young versus the old, which is why we have those organic textures in place. It’s interesting how many people pick up on the anachronistic aspects of the ’80s-era soundtrack, but not as many people realize that they’re heavily in play with these organic aspects. I appreciate you bringing that up.

At one point, this mournful trumpet solo enters the mix – very analog.

And we’ve got sax, we have tons of flute, we have zither, and percussion played by [New Age multi-instrumentalist] Laraaji. We have a children’s choir. We have an adult choir, we have strings, we have harpsichords, organs, fretless bass, all kinds of mallet-based [instruments] digitally sampled, pulsing away, so, yeah, there’s a whole bunch of stuff.

Tell me about the “Fishbowl.”

It’s a studio cubicle in Midtown [Manhattan] with all of these weird little editing suites. We called it the Fishbowl because it had sliding doors so you could see into everybody’s sh**. We were surrounded by people making podcasts about weed and stuff while we were trying to do this serious thing.

How’d you wind up there?

We needed to be close to Josh’s office and home because his wife, Sarah [Rossein], one of the producers on the film, was pregnant with their second child. I live outside the city in the sticks. I would have loved to have worked on the score here.

“The sticks” being upstate New York?

I’m in the Tri-State Area.

Okay.

So I say, “Josh, come up here and work with me, get away from it all. And he was like, “I just can’t. Sarah’s pregnant, so let’s find somewhere close to the office.” But there’s nothing near the office, unless we were rich beyond compare. And Josh says, “No, let’s go the other way. Let’s just find some destitute hole in the wall.” And I’m like, “You want to bring us back ten years in the past to how we started?” Because we used to work across from a matzah factory in Bushwick, with rats running up and down the hallway. Literally. So now we’re one slight level above that. It was kind of adversarial in the same way that Josh is pitting Marty against the world. I guess he didn’t mind, in his mischievous way, doing that to the music department as well.

Less than ideal.

But after a while, it’s kind of like Stockholm Syndrome – it’s home! We plastered the walls with these gigantic black and white prints of the real people who inspired the characters in the film, so there are all these strangers on the wall, like a parallel universe.

In the Fishbowl, you’d go through the roughcut with Josh, figuring out what each scene needed in terms of music?

Yeah. I’d write parts, and then Josh and I would sit there and discuss various things—whether it’s a decrescendo or “How do we connect these two parts?” or “This thing is chock full of harmony; there’s no more harmony left to add, so what do we do here?” “How do we break up this chord into different sections of the choir?” I work with all the parts of the buffalo, but it’s my buffalo. I’ve never worked on a film where you make your little part of it, and then it goes on the factory conveyor belt over to some other place and comes back sounding prim and proper. I’d feel borderline suicidal if I heard my music demonstrated that way.

You develop your themes on the keyboard, then expand them into full-blown arrangements. How did that come about?

My score producer is also a conductor, Joshua Eustis. He conducted the orchestra and the choir in Vienna and Prague, respectively.

Classy!

The cool thing is, Joshua really gets my writing, so it wasn’t about “Let’s slap a big Hollywood score on top of this thing, like a f****** casserole.” No! Everything has to come from the heart, made to measure.

Before the sessions in Europe, I imagine you’d made demos, but what was it like when you actually got to hear your melodies being sung by a live choir?

Not good.

Oh, really?

Well, here’s the thing. I’m in Joshua’s earpiece while he’s conducting the choir. He’s my surrogate, and I’m Josh Safdie’s surrogate, so if the choir is just going through the motions or doing a polite thing, that’s never gonna cut it. It’s a Josh Safdie picture! I had to get in there and coax a little bit of a feral thing from the choir.

Not prim and proper.

And funnily enough, I was not present for the children’s choir because I was working on the final cues, but Josh went there with Joshua Eustis and did the exact same thing. It was too tight, so he loosens the air in the room, shakes things up, makes the kids laugh a little bit—he can be a goofball so he’s able to get people to be on his frequency.

Josh Safdie’s films are always packed with tension. What’s he like to collaborate with?

He’s like Marty Mauser, in a way—really driven. Nothing casual. Every inch of the movie is mapped out in his head.

How do you connect with such a specific vision?

Josh is open to negotiating but you have to beat his idea, and you have to beat his idea to a pulp. Largely, he’s not open [to suggestions]. He’s got his thing, and we, meaning his collaborators, appreciate that because it creates a kind of unity to the work.

Before you started scoring movies, you released several solo albums under the name OneOhTrix Point Never. How did you adjust to the task of making music that served the picture instead of your own muse?

The biggest adjustment is somebody else saying, “This is what I want.” You’re not the only cook in the kitchen anymore. For someone [like me] who’s a lone wolf-y kind of guy, that takes a little bit of adjustment. But I think my heart was really longing for it.

That’s interesting, given that you once said, maybe half joking, that you were too much of a megalomaniac to play in a band. Now you’ve become very adept at collaborating.

You just kind of get your reps in and then suddenly, you’ve arrived. And that’s cool. It’s really cool.

Marty Supreme is in theaters now.

Featured image: Timothée Chalamet. Credit: Courtesy of A24