Editor’s note: Spoiler alert! This story discusses plot lines of A Thousand Blows Season 1.

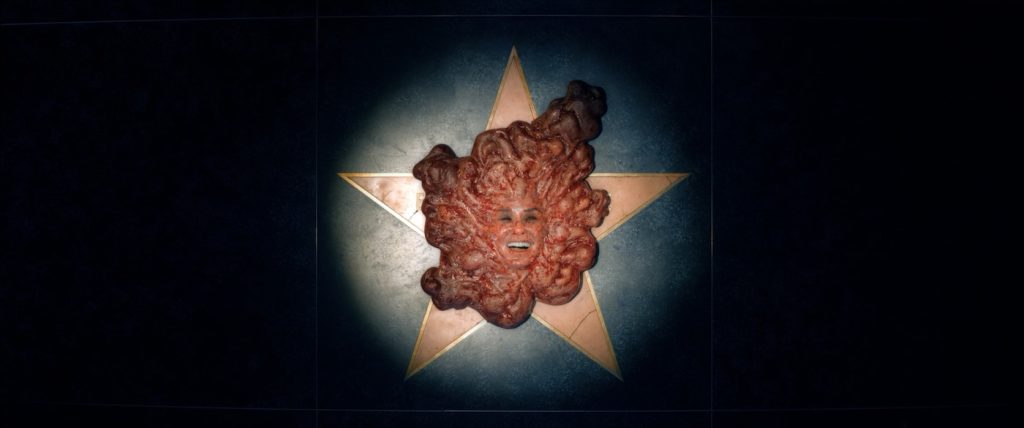

The subtle storytelling of Maja Meschede’s costume designs is hiding in plain sight if you’re able to look away from the simmering drama of A Thousand Blows, a six-part series from Peaky Blinders scribe Steven Knight that follows Hezekiah Moscow (Malachi Kirby) and his brother Alec (Francis Lovehall), two Jamaicans immigrating to London during the late 1800s. Hezekiah has dreams of being a lion tamer but is hoodwinked by a circus conman, and with only a few pence in their pockets, the brothers resort to bare-knuckle boxing to scrape by. A chance encounter with the Forty Elephants, a gang of thieving women corralled by the droll wit of Mary Carr (Erin Doherty), further spirals uncertainty in their lives.

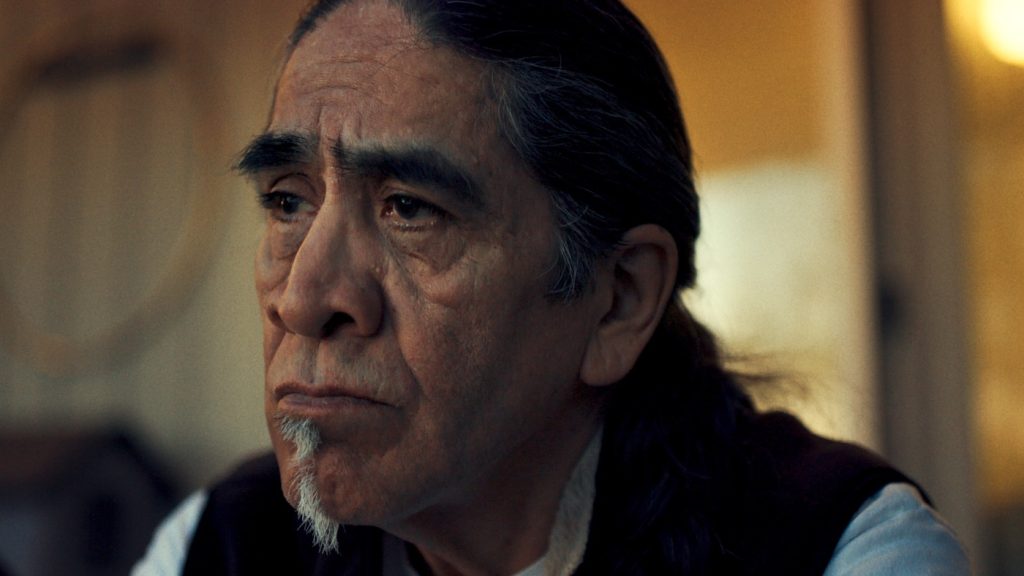

Knight gives viewers plenty to sink their teeth into (sorry, Mike Tyson), pairing a pulsing narrative that weaves the social class of London with complex characters whose names are torn from history books – Hezekiah, Alec, and the Forty Elephants among them, along with bare-knuckle boxer Sugar Goodson, brilliantly portrayed by Stephen Graham (who also serves as executive producer). Immersing the magnetic performances are moody textures, period wardrobe, and stylized regencycore hair and makeup. Meschede tells The Credits she had plenty of “design freedom” to express each character through costume.

When Hezekiah and Alec arrive in London, the customers dress them in outfits inspired by their native country. “When we first see them in the Victorian East End crowd I wanted them to really stick out. And as the color choice of Hezekiah’s first costume, I wanted it to subconsciously remind us of being in Jamaica, looking at the sea, the sand, and the light,” she notes. A straw hat added to the fish out of water feeling. “Nobody would wear such a straw hat in London because you don’t need that shelter from the sun,” she says. “I wanted Hezekiah’s costume to have this lightness. To feel like he just landed there and he has these hopes and dreams and no one will stop him.”

As Hezekiah becomes successful at boxing, his wardrobe evolves with him. “When he first arrives, he’s wearing linen and cotton. And then he manages to dress himself with his first winnings in a nice suit,” says Meschede. “I wanted him to conform at first because I think there’s an insecurity when you’re a stranger, a foreigner. But then later on, he expresses himself with more confidence.”

The costume designer admits there was plenty of work and research that went into the boxing matches featured in later episodes where the competitors fought with gloves. “I spoke to historians who specialize in Victorian boxing, and it’s hard to find anything original. We had so many fittings and had a special leather maker who made so many gloves for us. They had to look right; the weight, the thickness of the leather, the breakdown. The proportion of the gloves to make them work on a TV screen. They’re filled with horse hair, so we did quite a lot of tests,” Meschede explains. “And it’s really hard to make these gloves comfortable because of the way the thumb is cut, but the cast was totally on board supporting the costume and wearing them.”

Further thought went into detailing the four women of the Forty Elephants gang, played by Doherty, Hannah Walters, Darci Shaw, and Morgan Hilaire. “The characters are based on real women, and they’ve gone through a lot in their childhood and as teenagers. I’m sure life was extremely tough, but nevertheless, they found a way to survive. They found this group of women who became amazing thieves and very skilled. I wanted them to stand out,” Meschede notes. Period fashion provided the influence. “I looked at Victorian silhouettes, which I think are very powerful for recognition value and feeling like you’re in that time. Then, to express the rebelliousness of the characters, I used strong silhouettes and worked with brightly colored fabrics and patterns. I wanted them sometimes to really clash, to express this vibrancy, their power, and how they’re being really bold and confident.”

Another consideration for the Forty Elephants was the class divide between the East End and uppity West End. “Women of the East End at that time could have never afforded any silk, any lace, or anything handmade or custom made. So they really look almost out of place marching through the streets of the East End. I made sure the clothes looked used. They’re not perfect or brand new from a tailor, so they can melt into the background.” Garments were sourced from local UK vendors, handmade, or by altering existing period attire.

We’re introduced to the quartet early on in episode one in a scene where Mary screams in pain, clutching a baby bump among a crowd of concerned Londoners. However, it’s all a ruse, allowing the posse to pickpocket them – a scheme Hezekiah figures out from the jump. “When Mary pretends to give birth, they are kind of in cloaks and hiding away,” Meschede says. “I chose more subtle colors, but what we did was buy fabrics that were really bright, and then we dipped them. So you have vibrancy in the fabric, but it’s far more subtle. At the same time, we chose fabrics with really bold patterns that clash because I think that creates a wonderful energy that really stands out, but they can still blend into the rowd.”

As the story reaches its climax in episode six, Hezekiah and Mary find themselves in a position to forever change their lives. Hezekiah is to fight boxing champion Buster Williams (Nathan Hubble), and the Forty Elephants use the crowded venue as their biggest score yet.

Meschede dressed the characters to reflect their character arc, with Mary wearing a show-stopping red gown. “There’s an evolution for each character. Some women become stronger and some women not,” she says. “And I don’t want to give too much away, but whoever didn’t feel like that, I faded the colors.” For Hezekiah, he reverts to his Jamaican roots, dressing in attire he wore when first arriving in London. The subtle touch brings the character full circle.

A Thousand Blows is streaming on Disney+ and Hulu, and Season 2 is already in the works.

Featured image: A THOUSAND BLOWS – “Episode 2” – After their brutal fight, Hezekiah finds himself firmly in Sugar’s sights. Mary steps up the plans for her heist and recruits the help of both Hezekiah and Lao. The Forty Elephants carry out a raid on Harrods, whilst Alec makes a new acquaintance. (Disney/Robert Viglasky)

STEPHEN GRAHAM, MALACHI KIRBY