Oscar-Nominated “Hamnet” Co-Screenwriter Maggie O’Farrell on Adapting Her Novel with Chloé Zhao

With eight Oscar nominations and a string of trophies thus far, writer-director Chloé Zhao’s historical fiction Hamnet anchors the story of what inspired one of the greatest works ever written, William Shakespeare’s (Paul Mescal) deathless play “Hamlet,” not in the bard’s brilliance, but in the story of his luminous wife, Agnes (a devastatingly raw performance by Jessie Buckley), an herbalist. The story takes off when their son, Hamnet (Jacobi Jupe), dies, and the couple spirals down a vortex of grief and depression just as William’s playwright career blossoms in London. Newly minted Oscar nominee, co-screenwriter Maggie O’Farrell, was thrilled when she was offered the opportunity to adapt her 2020 novel with Zhao. “When I heard that Chloé wanted to write the screenplay with me, I wasn’t going to say ‘Yes’ at first.” But Zhao ended up changing her mind: “I remember her holding up the book saying, ‘I want to make a film of the book.’ I thought, ‘Why the hell not?’ And who would say no to Chloé Zhao? So, I thought I’ll give it a go. I’ve learned an awful lot. By the end of our first conversation, I agreed to write the first pass and sent it to her in two months.”

O’Farrell spoke to The Credits about her screenwriting debut, what drove her to write the historical fiction novel in the first place, and why art is crucial to understanding humanity and ourselves.

What were some of the elements that brought you and Chloé together on this project?

We both really love Terence Malick films — she talked about Terence as an influence for this film. We also love the films of Wong Kar-Wai; Chungking Express is one of our favorite films. Chloe and I have very different skills that are quite complementary, which was a strength in our collaboration. She loves voice notes – I live in Scotland, and she was mostly in California — so this screenplay was forged by voice notes. I often woke up to 12 or 13 voice notes, each a couple of minutes long. One of the longest that I recall was 58 minutes. She talks through her thought process, whereas I always have to work things out by writing them down.

Since Hamnet was your first screen adaptation, how did you find the process?

It was really fascinating. The first job was to somehow reduce the 350-page book down to a 90-odd page screenplay. There’s a lot of just distilling and distilling, but I learned a lot about cinematic language from Chloé. The things that work on the page don’t really work on the screen.

What are some of the material changes in the movie?

Probably the biggest change is the chronology. The book begins on the day the twins get ill and moves back and forth – it goes back to the time when William and Agnes meet. That works fine on the page, but can be a bit jarring to a cinema audience. So, we had to disassemble the story and put it back together chronologically. There’s a bit more about Agnes and Will’s parents in the book; quite a lot of it was filmed, but it didn’t make it.

In the opening scene, Agnes lies down in a fetal position embracing the tree, which cements her deep connection to nature. Why was it important to start with that scene in the film?

Novels are interior; the reader is a party to the innermost thoughts and emotions of the characters. But obviously, you can’t do that for cinema, so you have to find another way of communicating it. In the novel, when Agnes goes to see “Hamlet,” she goes into the theater on her own, and her brother stays outside. But in the screenplay, we brought him in so that she could talk about what she was feeling. Another way Chloé does it is by sublimating. If you have a character who is feeling a lot but doesn’t express it, you can sublimate it into the environment. In that scene, you see Agnes’ contentment and turmoil. The sound in the film is so good that with the shots of the forest, you can see what she’s feeling without really realizing that you’re seeing it.

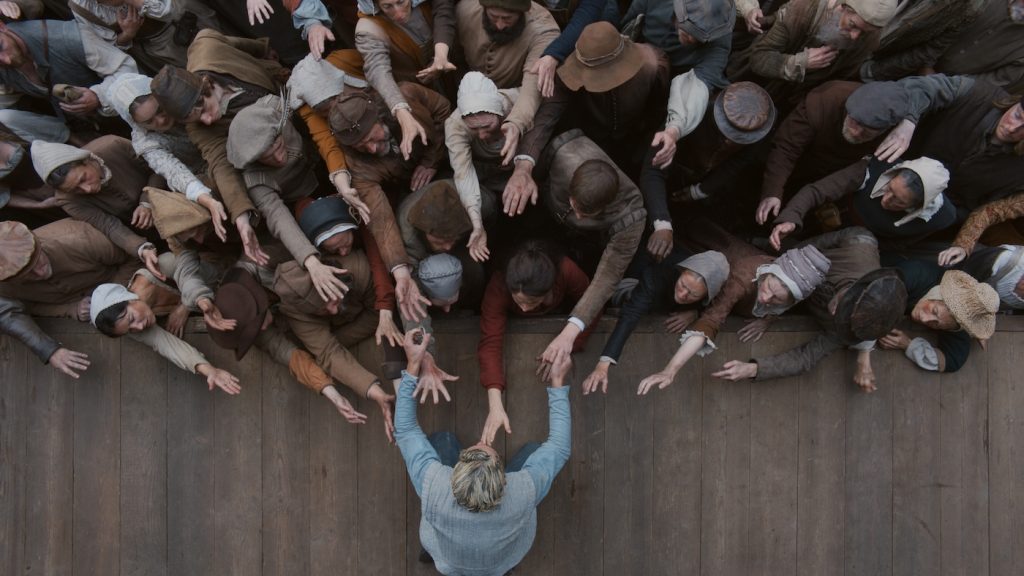

In the final sequence of Will’s stage play, the reaction shots were quite raw as he stood in the wings, watching Agnes react onstage. Is that from the book?

Yes, but in the book, it’s very telescoped, mostly because you can’t have a massive speech and expect your readers to stay with that. So it’s much shorter, but basically the same scene, just a bit more fleshed out in the film. That’s one of the joys of the film for me: that scene is expanded so you see a lot more of the play—you get that physical proximity to the players [stage actors] that the audience had in those days. And then you see that glance between the two of them. It’s contracted in the novel and leaps forward to them leaving the theater together before coming back to the final line in the book, “Remember me” from the ghost speech. Cinema enabled us to make that a lot longer, which is a real joy. If I had a time machine, I would absolutely go back to The Globe to watch that first performance of “Hamlet.” And in a way, now I have!

Did anything surprise you in terms of how that climactic sequence turned out compared to how it unfurled in the book?

I think it’s beautifully done in the film. We did a lot of rehearsals with the players. There was a day when we brought Jessie and Joe [Alwyn, who plays Agnes’ brother, Bartholomew] to the audience with the players on stage, and that was incredibly exciting. It almost felt as it would have a long time ago, that you create this thing and suddenly there’s an audience who didn’t know the story of Hamlet. They had no idea there would be a swordfight and that someone would die at the end, as we now know. But it would have been deeply shocking when the ghost appears, or when Hamlet dies at the end.

What prompted you to write a story about Shakespeare that centers on his relationship with Agnes?

One of the reasons I wrote the book was that I’ve always felt that Agnes, or Anne Hathaway as she’s more commonly known, has been treated badly by history. People for years have wanted to give them a retrospective divorce: they’ve said terrible things about her, none of which have any basis in fact or evidence. They claimed she was illiterate and stupid, that he hated her and trapped him into marriage. People have been trying to denigrate her for 500 years. With the book, I wanted to encourage people to forget everything they think they know about them and their marriage, and open themselves up to a new interpretation. Maybe they really loved each other and were very much a couple right to the end of their life. When he retired from the stage and left London, he could’ve lived anywhere in the world, but he went back to Stratford to live with his wife for the final years of his life, which I think is hugely significant. There’s not a lot known about her — there’s no record even of her birth. We know they got married, she had three children, one of them died, and they moved houses. She also ran a malting business at one point from the back of the house. People in those days didn’t drink water because it wasn’t safe, so they used to drink ale.

Credit: Agata Grzybowska / © 2025 FOCUS FEATURES LLC

Did that come up in your research for the book?

Yes. There’s no shortage of books about Shakespeare, so I read as many as I could, but there was also a lot of research. I went to Stratford, where you can see the house they lived in; it’s extraordinary that it’s still there. You can walk through the house where Shakespeare once lived, stand in the room where he was born, and in the dining table where he used to dine. The Hathaway farm is still there. I also learned how to fly a hawk and planted my own Elizabethan medicinal garden, which I still have at the back of my house. Since the women’s lives in the book are not well documented, getting my hands dirty was the only way to gain a better understanding. I learned how to make medicines and made bread from a Tudor recipe!

How did the bread turn out?

My children ate it all up!

What would you like the audience to take away from the film?

The book is about where art comes from and why we need it. I’ve always felt that there’s a very significant link between “Hamlet” the play and his son Hamnet. If you look at the play through the lens of Hamnet’s death, you can briefly see Shakespeare becoming visible as a human being, as a grieving father, and the play is a message from a father in one realm to his son in another. That’s why we need art, to be able to understand these things and to see ourselves in it.

Hamnet is playing in theaters now.

Featured image: Director Chloé Zhao with actors Paul Mescal and Jessie Buckley with on the set of their film HAMNET, a Focus Features release.

Credit: Agata Grzybowska / © 2025 FOCUS FEATURES LLC