Oscar-Nominee Brendan Fraser on his Deep Dive into “The Whale”

Filmmaker Darren Aronofsky often pursues the road less taken in movies like The Wrestler, Black Swan and Requiem for a Dream. He’s done it again in The Whale, which stars Oscar-nominated Brendan Fraser as Charlie, a 600-pound English teacher who conducts classes over Zoom with his screen image hidden so students can’t see his true size. The entire film (now available on demand on Prime Video, Apple TV and elsewhere) takes place inside Charlie’s apartment, where he argues with his caretaker (Oscar-nominated Hong Chau) and tries to reconcile with his estranged daughter (Stranger Things star Sadie Sink) while suffering from a heart condition. Fraser’s transformation into an enormous man makes for riveting spectacle, but, the actor insists, “This not a film about an obese man. It’s about a man in search of redemption and the breathless [suspense] that comes with whether or not he will achieve it.”

Fraser starred in his first blockbuster The Mummy in 1999. Since then, he’s made dozens of comedies, biopics, action pictures and dramas, including Gods and Monsters opposite Ian McKellen. But until last month, Fraser had never been nominated for an Oscar. His children woke him with the news, armed with ice cream, cake and balloons. Fraser says. “To share that moment with my kids, it’s among the top five happiest days of my life.”

Fraser, who lives in upstate New York with his family, spoke by phone during a recent visit to Los Angeles, detailing the nuances of his Whale hero and offering some hard-earned advice for young actors.

You imbue Charlie with so much heart and soul. How did you go about understanding the psyche of this troubled man?

On one hand, he’s the victim of having fallen in love with the wrong person so there’s the fallout from that cataclysmic event. And then knowing that a child got lost in the mix, whether it’s because of a court action, his former wife’s drinking, maybe his economic status — we don’t really know the reason, but what it means is that his little girl got compromised. When we meet Charlie, he’s dealing with the ramifications of this life he’s lived, the regrets, the failures. He has possibly five days left [to live] so he makes this Hail Mary to reach out to his daughter and apologize. I just had intense empathy for this character, and somehow the love I have for my own kids — that fueled me.

You shot The Whale during Covid. How did the pandemic impact the vibe of this film?

We were frightened, living under existential threat: Will there be a tomorrow? I’m not trying to be dramatic, but it wasn’t lost on all of us that this could be the last time we ever get to make a movie! But it was important to get up off of the couch, like Charlie must do, and go back to work. The pandemic made us all realize how much we cared about what we were doing.

The prosthetics in this movie are sensationally seamless. Had you ever done extensive prosthetics before The Whale?

In Bedazzled, directed by Harold Ramis, I played a guy who goes through five different incarnations in this Faustian bargain he makes with the devil, Elizabeth Hurley. There were a lot of transformative prosthetics, but it was the traditional process: you get a life cast done, they put goop on your face, straw through your nose, a mold is made, it’s compounded into sculpting for an appliance — nose, cheek, whatever — and then applied to your face. There are seams, but the audience buys into it because there’s a suspension of disbelief.

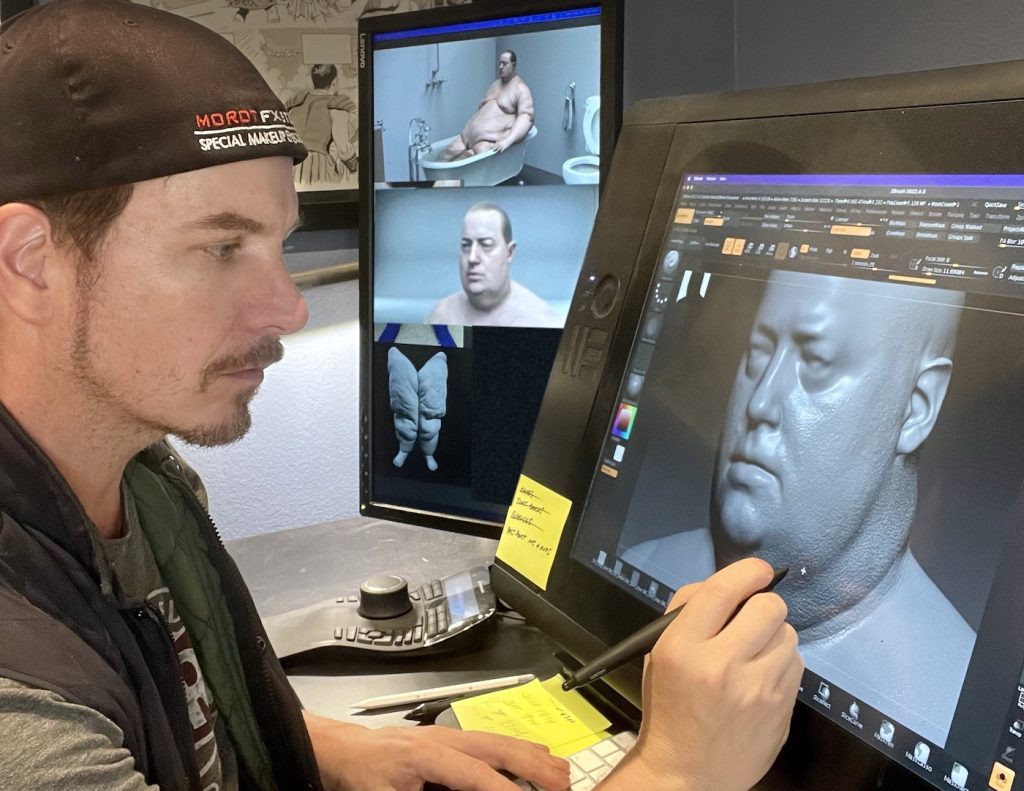

The Whale sets a new standard in photo-realistic prosthetics, with Adrien Morot earning an Oscar nomination in the makeup and hairstyling category. How did you get fitted for the “Charlie” fat suit?

I couldn’t sit for a mold because of the virus so the producer had this iPad and did a digital scan of my body in my driveway in freezing January. From that body scan, data was sent to Arden Morot in Montreal. He imported the data to create a virtual Charlie body, with absolute dominion over the placement of pores, skin anomalies, everything. He imported textures so [the body] became like a giant texture map. From that data, molds were 3-D printed, appliances were made to fit my face perfectly, and you never see the construction line.

From the outside in, “Charlie” represents a marvel of technology, but you had to animate his physicality from the inside out. What kind of research did you do in preparation?

I watched documentary and reality television footage with the volume turned down because I wanted to study bodies and their centers of gravity. I wanted to understand the mobility issues and disabilities and challenges faced by those who live in larger bodies. I also took inspiration from the great creatures of nature. Watching a great white [whale] crest and break the water and come down? To my eye, it’s reminiscent of the silhouette we see [at the end of the movie] when Charlie takes to his feet.

Movies rarely feature characters like Charlie in the lead role. Was it important for you to shine a light on the ways society as a whole views people who are heavy?

Yes! I worked with an advocacy group called the Obesity Action Coalition. Their mission statement is to end the bias that we as a society uphold as an accepted norm. The Coalition wants to make corrections wherein we don’t refer to people who live with obesity with the prevalent terminology. It’s not fair and we can do better. It’s the Coalition’s belief, and I concur, that this character Charlie can save lives by changing someone’s heart.

Audiences have responded deeply to your performance, famously giving you a six-minute standing ovation after The Whale screened at Cannes. What do you make of that?

When Charlie chooses to get up on his feet under his own power, which he could not do before, and goes to the light? I think that’s why audiences are having this collective – I don’t know if you call it catharsis or what — but there’s this undeniable emotional response from people in the audience taking part in this ritual that is cinema, sitting in a dark room with strangers, hopefully, checking their biases at the door.

Darren Aronofsky is such a distinctive filmmaker, always bringing a very specific vision to his projects. Who are some of the other directors you’d like to work with?

I’d like to work with Martin Scorsese again. Here’s the drill when you work with a masterful filmmaker like him: Everybody’s at the top of their game, all departments, and they’re all standing by like sentries. I’m serious! I gladly waited for a month to be called in for five or six days on Killers of the Flower Moon. There were a couple of scenes that Martin decides he wants to put in: “Call Brendan, can he get here now?” “Yes, I can!” I jump in the car and go. We’re all duty-bound to give Martin Scorsese what he needs to make the piece the best that it can be because we’re in service of something higher than our own interests. That’s the way I felt.

You’ve been acting professionally since you were about 22 years old. Back in 1992, when your first big movie Encino Man came out, did you ever picture yourself being nominated for a Best Actor Academy Award?

Are you kidding me?! No. Way. If I had allowed myself the fantasy, it would have been the category I’ve always admired: supporting actor. I’ve always wanted to be the bass player who backs somebody up and is really good at it. That’s how I felt when I worked with Ian McKellen [in Gods and Monsters]. He’s the lead guitarist.

In your field, career longevity can be a rare thing, yet you’re still going strong after three decades in show business. What advice do you have for actors who are in it for the long haul?

Have courage. Acting is about wanting and wanting and wanting again. There’s always going to be something in the way. An obstacle. And the actor’s job is to get around the obstacle and achieve the objective. And how you do that all comes down to tactics, really. Whether it’s a film, a play, or just the business itself, you need to want and want and want again. And to do that, you need courage. And to have courage is to acknowledge that something is scary. You can’t have courage until you acknowledge that. Thirty years ago, as a young actor myself, I would have done well to have somebody telling me to have courage. It’s something I learned by not achieving the goal, by being stopped by the obstacle. Living in this city is an obstacle: You’ve got to take Fountain because if you take Sunset, you’re going to get stuck in traffic. Finding an agent? That’s an obstacle. Staying in the game, staying relevant? That’s an obstacle. So that’s my epistle for the day. A hero is not just some guy running around in a helmet with a sword and a round shield. It’s a guy like Charlie. He’s a hero.

For more on The Whale, check out this story:

“The Whale” Oscar-Nominated Prosthetics Artist Adrien Morot Breaks the Mold

“The Whale” Screenwriter Samuel D. Hunter on Hard-Won Hope

Featured image: Brendan Fraser. Courtesy of A24