How Composer Alexandre Desplat Put a “Dada-istic” Spin on “The French Dispatch”

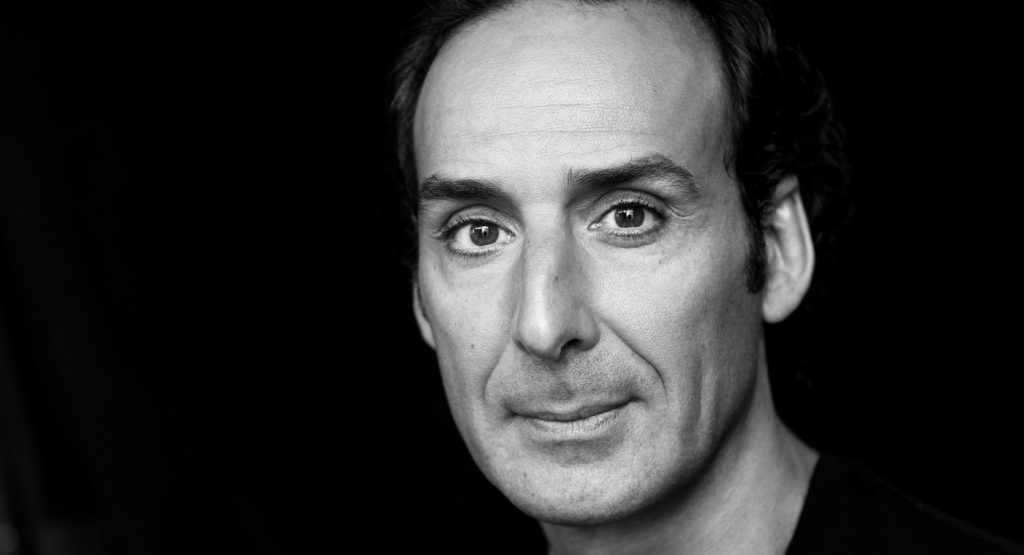

Wes Anderson’s dollhouse-perfect motion pictures radiate an unmistakable sensibility brought to life by a remarkably consistent team of below-the-line talent. His last four movies featured contributions from the same production designer (Adam Stockhausen), the same cinematographer (Robert Yeoman), the same music supervisor (Randall Poster), the same costume designer (Milena Canonero ), and, crucially, the same composer: Alexandre Desplat. An eleven-time Oscar nominee and winner of two Academy Awards, Desplat teamed with Anderson on Fantastic Mr. Fox, Moonrise Kingdom, The Grand Budapest Hotel, and Isle of Dogs before creating the pared-down score for his current release The French Dispatch.

Desplat’s quirky piano pieces complement the movie’s New Yorker-inspired vibe. Set in the fictitious village of Ennui-sur-Blasé, Dispatch casts Anderson regulars Bill Murray, Owen Wilson, Frances McDormand, and Tilda Swinton along with newcomers Benicio Del Toro, Timothée Chalamet, and Jeffrey Wright in three un-related stories bound together by Anderson’s eye and Desplat’s ear.

Freakishly prolific, Desplat scores up to 11 movies a year, customizing his musical palette to suit each project’s personality. Taking a rare day off in Los Angeles, Desplat explains why Wes Anderson never over-explains and how he found inspiration for The French Dispatch in Marcel Duchamp and Duke Ellington.

From one film to the next, each Wes Anderson movie requires very different music. For your Oscar-winning Grand Budapest Hotel music, you drew on the Central European folk song tradition; in Isle of Dogs, Japanese Taiko drums played a defining role. What was your key influence for The French Dispatch?

It started with the script. After I finished reading The French Dispatch, I told Wes it was the most dadaistic script he’s ever written.

As in Dadaism, the European avant-garde art movement?

Yes, artists like Marcel Duchamp from around 1915 to about 1925.

How so?

There’s no logic, no linear storyline. It’s provocative, fun, surprising so to me, the script was really Dada-influenced, even though Wes didn’t know that. I told him and suggested that the score should also be as strange and sparse.

You keep it sparse right from the start, using only solo piano to accompany the story about Benicio Del Toro’s criminally insane artist.

He’s a silent man who paints abstract paintings of a naked model [Léa Seydoux] who turns out to be a prison guard in this huge empty space. It seemed very Dada to have these sparse piano notes resonating in a huge venue. The piano became the core of the score, which lends the film continuity. As the story goes along, we have different instruments joining [the piano]. Harpsichord, tuba, bassoon, mandolin, banjo. But piano – – that’s how we started.

Your most prominent theme recurs throughout the film’s climactic story about the kidnapping of a police chief’s son. For “Police Cooking,” you used a grand total of three notes played in the piano’s bass register with the left hand.

You’re probably thinking of this. [Desplat plays the piano riff].

Yeah, it’s kind of hypnotic! Why did you come up with such a simple melody?

There’s so much to watch and pay attention to with the visuals. On top of that, actors are delivering pages of lines, so if I had written a crazy full-speed bombastic score, there’d be no way you would be able to digest what’s going on. Therefore the music needed to be obsessively repetitive. It reminds me of what I did on [2004 Nicole Kidman movie] Birth. I used four flutes for the opening and repeated that, with some variations but always at this high register. That allowed me to do anything with the rest of the orchestra – – French horns, tubas, strings, bassoons. Here it’s the same concept except it’s just a few instruments.

It feels like the music leaves room for the performances to breathe?

If I’d tried to do more, it would have killed the actors, making it impossible to listen to them, follow them, be attracted to them. The music would have just taken over. That’s why I needed the music to be sparse, and uh… inexorable.

The music cues do an uncannily effective job of complementing the eccentric characters who get caught up in this zany scheme.

It shows that you don’t always have to be bombastic Sometimes you can be minimal and still be musical and efficient. That’s one of the things I learned from doing so many European movies as a young composer. Before I became a Hollywood composer.

Well, you write to the movie. If you’re scoring a Godzilla. . .

Of course. If there are buildings falling down and planes exploding, yes you have to be bigger.

In French Dispatch, the fictional singer “Tip Top” sounds like an homage to real sixties French pop star Christophe. Did French musical traditions influence your score for this film?

Aside from the [Dadaism-era composer-pianist] Eric Satie reference, no. When I saw the first edit of the film I came up with this jaunty, bouncy [singing] “doo doo doo doo doo doo doo.” There’s something almost jazzy about it, from the twenties, like very early Duke Ellington around 1928, coming from ragtime with the left hand. I gave a concert yesterday at the Wallace Annenberg theater here [in L.A.] and realized the music for this movie is actually more American than French.

That’s right. The opening number features a tuba that would sound right at home in New Orleans.

And then harpsichord. It’s a strange cocktail.

So Wes Anderson shows you a rough cut of the film, you score to picture and then, did he give you a lot of notes about what he likes, what he wants, what works, what doesn’t work?

I would say that directors who talk less are always more efficient with me. I know how to read between the lines. It gives me more freedom – – even though it’s fake freedom because there’s no freedom when you’re a film composer. But you feel as if you can express yourself much better rather than having a director explaining every shot in detail. A Wes Anderson, or a Roman Polanski, or a Stephen Frears – – they don’t talk much. They’ll give you just little hints of what you should try, and that actually allows you to fly, quicker.

Sounds like you’re already on the same wavelength.

I wrote ten or twelve pieces, maybe more, but we chose the ones that are in the film. Then Wes goes into the editing room, interweaves the music into the picture very intimately, then I go back and add another layer of instrumentation or orchestration. It goes very fast because we understand each other very well.

When you saw the French Dispatch final cut for the first time with your music, how did you react?

What really stunned me was not the music really but the virtuosity that Wes has achieved with his directing. Whew! He’s so strong. I mean, I’m not sure people understand how incredible his technique is. For what you call below the line – – cinematography, furniture, sets, costumes – – it’s mad, it’s crazy – – the hair, the makeup, and it’s all one man, all Wes, all coming from his mind. That’s very rare.

You’re in Los Angeles at the moment. Are you working on a new movie out here?

I just finished one for Stephen Frears [The Lost King] and I’m about to start a Moliere play.

Setting aside for a minute the high quality of your film scores, the sheer amount of work you produce makes most composers look like slackers by comparison. How do you create so much music?

Well, I’m given good films. If you’re given good films with good people and you work eighteen hours a day, then you’re covered.

Featured image: (From L-R): Lyna Khoudri, Frances McDormand and Timothée Chalamet in the film THE FRENCH DISPATCH. Photo Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures. © 2020 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved