Industrial Light & Magic Senior Creature Artist Dane Larocque on Constructing Unforgettable Creatures

Dane Larocque hails from rural British Columbia and Alberta and grew up in what he calls a “hardcore western rodeo family.” A career in visual effects, at arguably the most prestigious VFX company on the planet, wasn’t something he grew up imagining as an option. Yet Larocque had an enduring passion for film and was the type of kid who’d pore over the special features of a DVD to see how a particular film was actually made. “I think it was when I was about 14 or 15, I was like, ‘wait, people do this as a job!?”

Cut to today, with Larocque working as a senior creature artist at Industrial Light & Magic, the VFX shop created by a little-known filmmaker named George Lucas. ILM was founded in May of 1975 when Lucas began work on Star Wars—40 years later, Larocque would be working on Star Wars: The Force Awakens after stints working in the oil, construction, and car restoration industry, to name a few.

We spoke with Larocque about his career, learning from the best at ILM, and using what he’s learned to make his own creature feature. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What was your childhood like?

I grew up in rural BC and Alberta. Jumped back and forth a bit. I come from a really hardcore, western rodeo family. We raise horses, train ‘em, break ‘em and compete with them. But I always had this really hardcore passion for film. I remember when I got Twin Towers on DVD and I watched the special features endlessly and I think when I was about 14 or 15 I clued in and I was like, ‘Wait…people do this as a job!?’ I was always fascinated with Star Wars and especially Jurassic Park. I was always a dinosaur nut, drawing monsters and creatures and stuff like that all the time.

Yet you didn’t go to film school, right?

After a while, I dropped out of high school in grade 10, went to work in the oil patch, did a whole bunch of jobs like that. I did stucco, molder mediation, construction, machinery, car restoration and I just got tired of that kind of instability. I got sick of it and took the risk, said ‘screw it,’ and packed up my truck. I moved out to Vancouver and lucked out with one of the colleges out here. They put me in the right program and because I was really into drawing, I studied 3D modeling for games and animation and it was kind of the perfect program for me to get started with because it was so art-heavy. I just fell in love with it.

How did you find your way to ILM?

After a couple of years of trying and a friend who got in, they ended up bringing me into ILM as a junior – back in the Warcraft and Star Wars: Force Awakens days. I just worked my butt off trying to make sure that they wouldn’t let me go. And now it’s about six years later.

When did it hit you that you were working at the place that George Lucas built?

I was working on The Force Awakens and I was talking with a lead and we were going through our assets and the [lead] will critique and tweak your work. And I remember this lead was like, (whispered) ‘Hey, that guy over there built the original death star!’ I was like, ‘Whaaaat?’ It blows your mind sometimes. You’re working with people who have been in the industry that long – especially for such a young industry. I mean, VFX hasn’t been around that long, so it’s cool that ILM has that lineage.

What was it like to go from being the kid who pores over DVD special features to working on a Star Wars film?

When I was working on The Force Awakens, I really didn’t want any spoilers to happen, so I purposefully tried to hide from anything happening in the film because I didn’t want to see it. And I remember going to one of our internal reviews and the first shot they showed was the moment with Han getting zilched! So I was just like, “Welp. Alright! I guess I know the film now!” That’s a very vivid memory. But it was still very cool to be a part of it.

What about your experience working on Marvel’s Thor: Ragnarok?

I was someone who grew up as a hardcore Marvel fan. My older brother was crazy about Spider-Man, and he would always make me recite facts all the time. It was such a career highlight to be able to help bring Hulk to life in Thor: Ragnarok.

You also not only had a hand in Disney’s recent live-action Aladdin, but you’ve got a hilarious personal connection to the film, too.

Another career highlight. In my family, my nickname has been Abu since I was about 5 years old. My nieces and nephews know me as Uncle Abu. My brother, all my siblings and their friends know me as Abu. And it was crazy when we got Aladdin. I tapped my supervisor on the shoulder, and I was just like, ‘Can I make the monkey?’ And he was like, ‘Yeah, you can do Abu.’ I got to do a good chunk of the modeling, which is sculpting the asset’s body, and a lot of the facial stuff to try and make Abu a believable monkey. And that was just a big career highlight for me. And it was super cool that they actually let me have that.

Tell me about your own project you’re working on.

I’ve always wanted to try and make my own stuff but I honestly just didn’t have the confidence. I thought, [filmmakers] are way more intelligent, I’m just some bum from the country, I can’t tell those types of stories. I’ll just stick with my drawings and my creatures. But ILM enabled me to think that maybe I can create something.

How so?

I sculpt creatures for work, for crazy amounts of hours during the day and I’ll still come home and sculpt my own stuff. I’ve learned so much from ILM, I’ve seen how everything gets built, from pre-visualization (before they’ve shot anything) all the way through to the end of a project, just before we deliver it to theatres. It lets me fathom that this is a process that can be done and it’s given me the confidence to create my own stuff with all of these things that I’ve learned from ILM, and this industry, and the amazing people that I’ve worked with.

Tell me about your project.

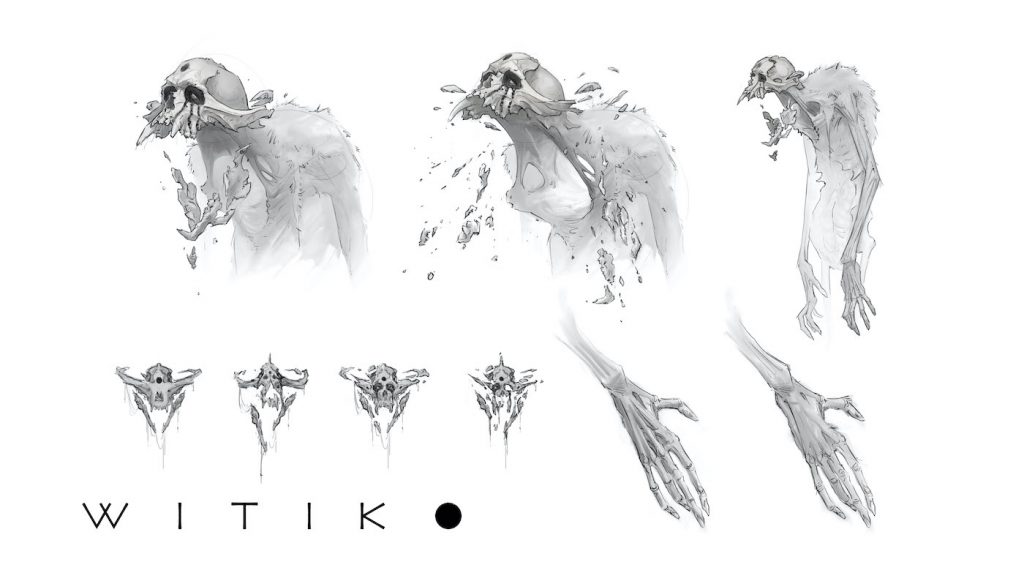

My personal project is called Witiko and it’s Indigenous influenced. I’m trying to stay authentic to Native American culture, because I have Cree and Sioux and a few others in me and my dad is status Chippewa. I feel like there are a lot of stories I can tell that also help empower communities to tell their story. Coming from the background I come from, I feel like a lot of the rural communities aren’t really known about, or authentically portrayed. There’s a lot of incentive for me to try and create stories that build around those experiences of growing up in those areas. To tie connections between western communities and my Indigenous heritage. A lot of those things I really want to help influence my future art and future projects.

I imagine you’ve got a great creature in Witiko?

The Witiko creature is an embodiment of this darkness or even mental illness. It’s super important to me to talk about these things through storytelling and I think it actually brings a lot of authenticity to things that don’t get represented that well. Thinking back to Alien, or anything Guillermo Del Toro touches, it’s magic. Those types of stories where the creature influences the themes and ideas of the film. With my project, I really wanted to just dabble in these ideas of trauma and emotional apathy, when you close yourself off and put yourself in that dark place. Everyone can understand disconnect from community, feeling emotionally drained or apathetic, or just being in a bad place. These things can be widely understood by everybody. So, playing with these ideas and setting them into a really authentic, traditional, well-represented setting is really important.