Editor Kirk Baxter on Syncing Three POVs Down to the Second in “A House of Dynamite” — Part 2

In the first part of our conversation with A House of Dynamite editor Kirk Baxter, the two-time Oscar winner (The Social Network, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo) talked about editing Kathryn Bigelow’s nerve-wracking nuclear thriller “A House of Dynamite.” Shot on three sound stages simultaneously to capture real-time reactions across multiple government locations, the film follows officials with only 20 minutes to stop a missile headed for a major U.S. city. Baxter revealed how he edited the film in story order for the first time in his career, maintained nail-biting tension without overwhelming viewers, and wove together three POVs down to the second.

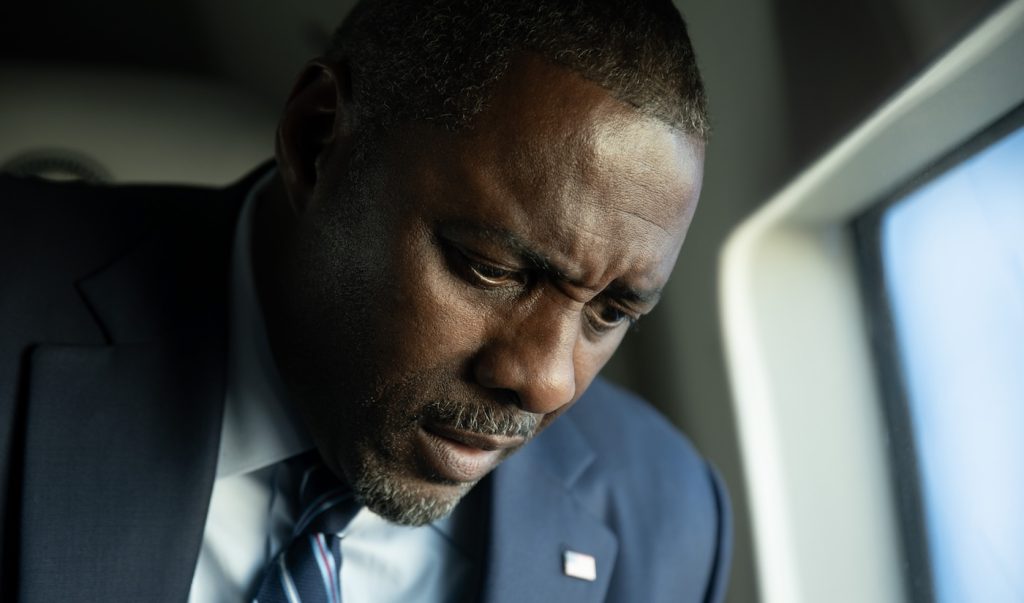

Filmed primarily in New Jersey thanks to approximately $30 million in production incentives, Bigelow’s thriller A House of Dynamite is a raw and nerve-shredding commentary on the unthinkable threat of nuclear conflict. Major sets in the film include: the 49th Missile Defense Battalion in Fort Greely, Alaska, tasked with detecting and neutralizing incoming nuclear threats; US STRATCOM (Strategic Command) led by General Brady (Tracy Letts); the 24/7 intelligence center in the White House Situation Room; and the PEOC (Presidential Emergency Operations Center), a secured communications center underneath the White House in the event of catastrophic emergencies.

Here is the conclusion of our conversation with Baxer.

In any given interaction among these characters, did you have the option to show their reactions on the display screens rather than their actual performance in the room?

Yeah, the scene travels as we bounce back and forth. A good example is when General Brady (Tracy Letts) at STRATCOM is talking to the Deputy National Security Advisor (Gabriel Basso) as he was going through security to enter the White House. I paid attention to where Gabriel was moving inside the White House rooms, where he crossed from one side of the screen to the other and changed his screen direction with his body movements. I had coverage of Tracy Letts from the left and right, as well as wide shots. So, I was always dancing around with how I was showing Tracy compared to Gabriel because it was a conversation without facing each other. I packaged it, moving really quickly but also neatly in a traditional filmmaking sense, so that the audience can consume it really quickly. When you cut different locations together, they landed with intention, as if it was designed to be exactly that.

What about layering in sound from the other perspectives to match every frame on the screen?

The delivery of a line and the musicality of a voice, of how something is said, really lodges in your memory. So, I didn’t want to hear the same lines delivered differently in different acts, say, when we see a character on the display screens from a different take than when you’re with that person in the flesh later in the story. So, I changed out what was recorded live when they were acting with these live screens because I wanted everything to be from the same piece of audio.

What were some of the elements that you had to navigate due to the shooting style?

You also have to consider how long it takes to physically do things compared to just being talked about. A good example is when Jared Harris’ character (Secretary of Defense) jumps off the roof. The first time I put that scene together was in chapter two, where you only hear it happening. The amount of time for that to happen and then for General Brady to respond to it, where he tells everyone, “No, no, keep your seats. Keep your seats”—didn’t require the same length of time as it did to physically walk across the roof, leap off, and have everybody rush to the edge, going “Holy sh*t!” So, once I built that, it taught me to go back into chapter two and expand the silence and pauses to make sure we hear all of that “Holy shit!” coming through his (Brady’s) phone feed. The push and pull to use the exact data and timing affected how the information flowed between chapters. Sometimes I needed to shorten things to make them match, but other times I had to expand them; it was a constant push-and-pull. Kathryn’s fast rule was whatever is emotionally the best is the correct choice. I would rather be wrong about continuity and right about how the viewer would experience the moment.

Even though the same event unfolds three times over the course of the film, it never feels repetitive. How did you manage that?

I always referenced the countdown because it’s a repetition of the same piece of information sliced up three different ways. In the first act, there are many faces that we can cut to between Greeley and the White House Situation Room, and we play it without any music. Just listening to the countdown is super effective — it sucks all the oxygen out of the room, you feel that pressure, there’s a pace and massive tension to it without any music. Then, the second time around, we have that exact same audio as a metronome. You’ve now got everyone in the PEOC and STRATCOM to work with. We put score under that to give it an evolution of experiencing the same storyline again, but now, we’re building on it with new bits of dialog that we carry into the third chapter. So, the President and Secretary Baker are hearing twice as much audio data. But now I’ve only got two faces to work with. So instead of moving quickly between everybody, I’m mostly sitting on Jared for really long stretches of time, and his death stare as he’s focused on the loss of his child, who is in the city targeted by the inbound missile. So, it’s bringing that same level of tension but without all the editing. I loved dishing up three different ways to deliver the same information.

The way that Kathryn ended it is the epitome of “less is more”—we don’t see how it ends.

Yeah, it throws it back to the audience. This is a procedural based on reality to expose the insanity of having 20 minutes to make a decision that affects humankind and the insanity of these characters who find themselves in a situation where they’re just not going to be informed.

What do you make of the ambiguous ending? What do you want to leave the audience with?

When we were making the film, it was kind of terrifying — all the articles that Kathryn sent to educate me on what we were working on were really frightening. By design, the movie doesn’t show a baddie. The point isn’t about who sent the missile or what the President’s response is. The point is about nuclear war. I know some people want bloodlust for the ending, but if we had a baddie, that would become the focus, or if we had this president in charge, they would have done this or that. My takeaway is: nuclear war is bad, no matter which way you slice it. It doesn’t matter how this thing ends, because there’s no good ending.

A House of Dynamite is streaming on Netflix.