Inside & Upside Down on “Wicked: For Good”: Production Designer Nathan Crowley on His Anti-Gravity Architecture

In order for production designer Nathan Crowley to be able to realize his vision for director Jon M. Chu’s Wicked films, he needed to assemble a crack team of artisans he has relied on for decades. Combining age-old skills and techniques with organic materials foraged from forests, seeing locations as sculptures that needed to evolve with the filmmaking and storytelling process.

Wicked: For Good focuses on the maelstrom surrounding Cynthia Erivo’s Elphaba, the so-called Wicked Witch of the West, and her evolving relationship with Ariana Grande’s Glinda, the Good Witch of the North. The Wizard (Jeff Goldblum) and Madame Morrible (Michelle Yeoh) see it as an opportunity to both exploit the demonization of Elphaba and use Glinda as a popular stooge for their dark agenda.

Here, Crowley, who won an Oscar for his work on Wicked and is also known for his groundbreaking work on Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy, as well as Nolan’s Dunkirk and Interstellar, breaks down designing a darker Oz and why the industry must act to protect vital trades.

What opportunities and challenges did the shift in tone and scale in Wicked: For Good offer you?

We spent a lot of Wicked getting the audience used to seeing Munchkinland and introducing people to the world. With the second film, we get to explore the whole of Oz. We travel between the Winkie and Kiamo Ko, the great forests and the Emerald City; we move through the landscapes and follow the Yellow Brick Road, thereby offering opportunities to view Oz as a place rather than individual elements. I enjoyed expanding the Emerald City because in the first film, we come in on the train, there is one short day, then we head straight into the palace through Wizomania. We didn’t spend much time getting to know Emerald City or the landscapes outside it. It’s a much more serious emotional film. It was pretty exciting to explain the characters and where they were, how Elphaba ended up being in Kiamo Ko, getting to explain what that is, and the architecture of this famous castle.

Why did you choose anti-gravity architecture to create Kiamo Ko?

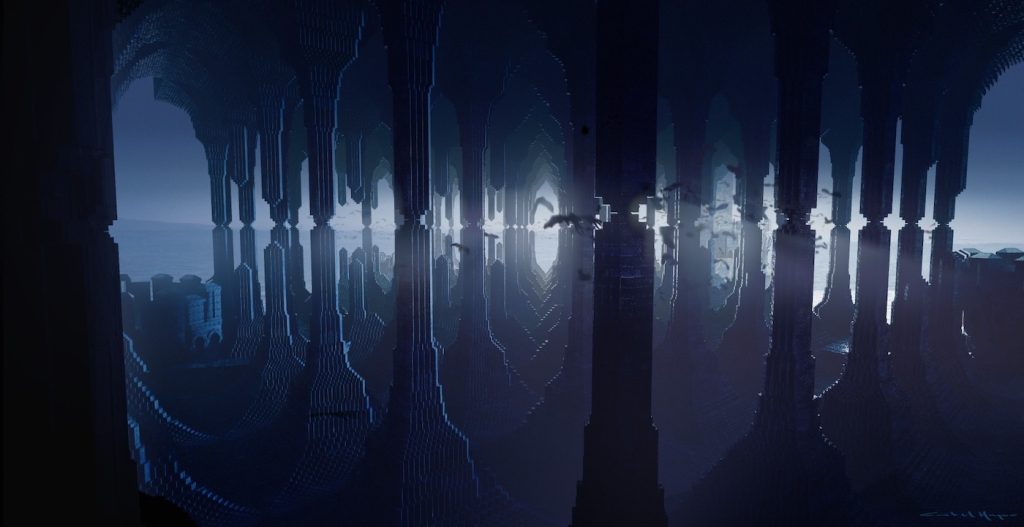

I knew we were at sunset, and I knew Kiamo Ko always appeared blue in the books and in The Wizard of Oz, so I knew I had to add some blue stone to it. However, the larger theory was that it was an old seat of Fiyero’s family, and I felt it belonged to the time of magic, when people could read the Grimmerie, so it was like, “We’re going to defy gravity.” My team suggested the columns not touch the floor but be floating, and that was the start. Now, what more can we do? Because we’re going to see this thing from the outside, we could float the battlements so it feels like it touches on the essence of the magic of Oz. Then there’s the realization that if you do arches, and upside-down arches, they become like opposing magnets, and you can get this sliver of light through the upper core of the profile of Kiamo Ko. It was a really a very subtle balance of architecture. I didn’t want it just to be granite because the architectural language of castles is big stone walls. I wanted to do it with a glazed brick, so it would make it more delicate and have more of a femininity to it.

Another iconic location where color is key is the Yellow Brick Road. How many shades did you go through to get the right one?

I have the scenic paint department, the general paint department, and the plaster shop, which produces the Yellow Brick Road panels; it was more than just the shade of yellow. It was also about the size of brick, the grout size, and even the depth of the grout. We had to do a ton of testing. The yellows were hard because you have to be this golden yellow, but at the same time, you need it bright enough that it’s the most powerful thing in the image. You have matte glazes and gloss glazes. On a stage, you can kick the roof lights, but you have to soften it outside. There, you have a one-directional light from the sun, and that will turn it white in reflection. At dusk, it would need to be a more powerful, deeper yellow, so we would change it depending on where we were. We must have repainted the Yellow Brick Road about four times. We don’t stop a visual design idea and hand it to visual effects. You get to build the whole set in a way that you can change it as you go. It’s like a piece of sculpture.

You used organic materials in the design of Elphaba’s nest. Is it true you had people going out into the forest to find wood?

Yeah. We had this terrific greens department. For example, a farmer grew all the tulips, but we still had to grow an extra 600,000 in greenhouses for the Munchkinland set on top of that. With Elphaba’s nest, it’s supposed to be the canopies of the great forest of Oz, and the trees are circular, so we decided they would weave together. I was inspired by the work of British sculptor Andy Goldsworthy. I roughly knew the size we needed, and we marked it out with Jon so we knew where we needed the movement, got the view out to the landscape, where they enter, and we locked that first. Then the green department went foraging, got huge amounts of this flexible wood from their different sources, and dumped it all on stage. We needed people who could sculpturally blend and weave the wood together. When we hit problems with joins, because we couldn’t weave into the ground, we turned the wood upside down and came back up, like a rolling wave. We needed a tree to support the ceiling, so we sculpted it from foam, hard-coated it, painted it, and the greens department added the real wood branches. We joined them together with plaster. We needed to get some top light in there, too, but I didn’t want to see the grid. My plasterer said we would cast stuff in clear silicone, so they made some giant leaves in that and laid them on the canopy. It developed organically rather than as a plan of action.

Both films were shot in your native UK. Are there people that you always call in to pull off projects like this?

I have worked with the same people for 20 years. My scenic artist, David Packard, is the same person I’ve been using since Batman Begins. I carry all kinds of different people, and it’s not just from England. We have an art director from Iceland and one from Estonia, because we worked in these places, and you find people who are great at what they do. It’s about finding the people who are like, I’m going to try this, because you want it. You can’t do it alone. I need a construction crew that’s reliable and can take on challenges. They need to be optimistic about the challenge ahead because it is sometimes stuff we’ve never done before. I’ve never done spinning wheels for a bookshelf. We had to build a 106-foot-long clockwork train engine. Also, when it comes to miniature building, such as the model of Oz, I need people who know traditional crafts. I began at the old MGM Studios on films such as Hook. Hollywood was full of this. You just went down to the workshops and walked the street where they all were. That went away, but England kept up the training. When I’m doing something as big as Wicked, I don’t need one of the best construction people; I need 20.

Could more be done to protect those crafts?

It has been maintained in the UK because of the tax bill, so people have kept on making big films there, and the crafts have kept up. Here, they need to pass the training on. There are lots of great scenics. Ed Strang, who was on Dunkirk with me, is a great example. His grandfather used to hand-paint the posters outside Warner Brothers studios in the 1930s. That training needs to be passed down. There are very few miniature builders now. There’s plenty of CGI in Wicked, but the thing is the balance, so the audience doesn’t question it. The old Hollywood system was great, but that system can’t work in the modern era; somehow, these crafts have to get passed on, or they get lost. No one believes the amount of practical stuff we do. I guess we never told anyone about all the practical stuff in the Nolan films. In Dunkirk, it wasn’t CG planes; they were all flying miniatures. The fact that no one knows means it was successful.

Wicked: For Good is in theaters now.