“Super/Natural” Producer Tom Hugh-Jones on How His New Nature Doc Will Blow Your Mind

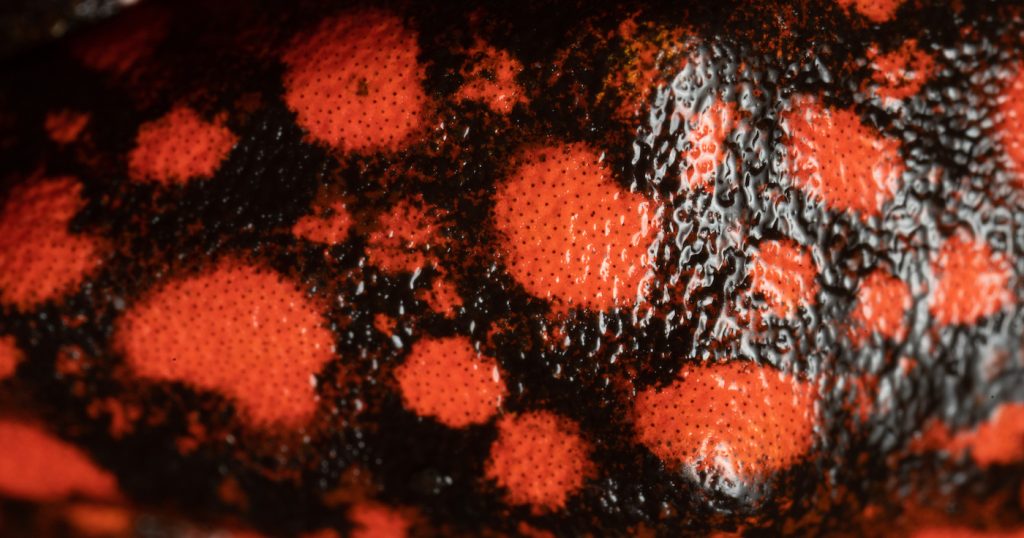

They call him Sarcastic Fringehead, and the gargoyle-like fish with its glow-in-the-dark inflatable mouth must be seen to be believed. A resident of the Pacific Ocean, Sarcastic Fringehead is just one of 40 or so naturally gifted characters filmed in their native habitats for National Geographic’s Super/Natural show. Executive produced by James Cameron with voice-over narration from Benedict Cumberbatch, the eight-episode series (which debuted on Wednesday, Sept. 21) features creatures great (elephants) and small (Mexican fireflies) as they engage in stranger-than-fiction survival skills. Captured with low-light cameras, hyper-sensitive microphones, and other advanced gear, the subjects of Super/Natural demonstrate ingenious communication skills incorporating everything from phosphorescent light to rarely recorded vocalizations.

Executive producer Tom Hugh-Jones, whose previous nature documentaries include the Emmy-winning Planet Earth II, says, “In making Super/Natural, we wanted to bring the latest research together with the latest technology to showcase things that are beyond human perception. I think our show will keep you on the edge of your seat because we’re trying to blow your mind all the time.”

Speaking from his home in Bristol, England, Hugh-Jones talked about technology, collaboration, and the wonders of the Little Devil Tree Frog.

James Cameron has Avatar: The Way of Water coming out in December but of course he’s been fascinated with cutting-edge camera technology for a long time. What did he bring to the table as an executive producer of Super/Natural?

Nat Geo suggested we partner with James because he’d worked on their series Secrets of the Whales. It was a great match. James and his team were constantly pushing us to be more adventurous with the visuals and the music and the narration and storytelling. He understands how to tell a story that engages people so they can relate to some strange beast like the jumping vampire spider.

You and your team do a great job of portraying tiny creatures. In Ecuador, for example, you film a frog the size of a thumb.

The Little Devil Tree Frog.

But you go a step further and photograph the tadpole baby on the Little Devil Tree Frog’s back. How do you film such small critters?

In the industry, we call that macro photography. There’s this whole community of people here in Bristol where it’s a little like Honey I Shrunk the Kids. They get a bit obsessed with tiny dollies and techniques for pulling focus remotely and moving the camera without touching it because if you touch the camera. You’ll send huge vibrations into the shot. There’s a real art to it.

The series documents incredibly inventive communications that take place within and even between species. For example, you show a squirrel mimicking the alarm cry of a chickadee to warn its neighbors about an incoming hawk. How did you record these sounds of survival?

Our sound men and sound women use contact mikes and high-level gun mikes to pick up the sounds. In some situations, we’ll make the sounds louder or slow them down in post. When you hear birds making these strange, high-pitched sounds, it’s so interesting to learn what it is that they’re communicating.

In this case, the squirrels and little birds are basically yelling at each other: “Here comes a predator!”

Run!

How did you capture that hawk footage?

We trained a Northern Goshawk from the time it was a chick to fly with a cable cam system called Mabel. Our cable run was about 300 feet long with high-speed Phantom Veo [cameras] onboard. Shots were achieved flying at 40 miles an hour one foot off the forest floor at 450 frames per second.

In your capacity as producer, do you travel to these wildlife locations yourself, or do you stay in Bristol?

On this one, I didn’t go on many of the shoots. A lot of this series was made during coronavirus, so we often had to operate remotely, collaborating with amazing camera people from around the world.

I read somewhere that you went with your parents to the Amazon when you were five years old.

Yeah.

How did that experience impact your view of nature?

I had a kind of wild upbringing anyway, and I was young enough to be quite accepting: “I have a pet monkey and a blowpipe, and I hang out with the tribal kids.” In fact, I had more of a culture shock when I got back to England: “Why is everybody wearing clothes, and why can’t I make a fire in the middle of the living room?”

Benedict Cumberbatch narrates the series, and he’s very engaging. How did he get involved in the show?

The credit has to go to the head of wildlife [programming] at Nat Geo, Janet Han Vissering. She’s very fond of Benedict and suggested him. We’d been going through a variety of names, but when we listened to Benedict’s voice, we realized he’s able to put drama and emotion into [the voiceover] without overplaying it. Of course, we also liked the connection to Doctor Strange. Super/Natural is almost psychedelic in how it brings out these amazing colors and strange experiences of the natural world so that connection seemed very apt.

Each of your previous documentaries had a specific theme. What’s the concept behind Super/Natural?

Human Planet was about tribal people. Hostile Planet looked at how the changing climate affects animals. On this one, we wanted to visualize things you can’t capture with normal cameras. We used thermal cameras to show how hot bees get when they’re trying to kill a hornet. We use ultra-high-speed cameras to reveal the mating displays of birds you can’t see with the naked eye. We use low-light cameras with the fireflies in Mexico during their nighttime mating ritual. Pretty much every sequence has elements in there that you couldn’t have captured 10 or 15 years ago.

Most of the segments feel character driven in the sense that you focus on one individual creature as it moves through a survival story with a clear-cut beginning, middle and end. That structure was deliberate?

Yes. We’re trying to bring this aesthetic from feature movies, where every shot tells a story and comes from someone’s point of view. That can be hard in natural history because animals don’t read scripts or behave on cue, but if you’re determined and clever about how you shoot, it can be done. On top of that layer, the mission of James Cameron and his team was to impart information in a fun way to people who aren’t necessarily fascinated by science. I’m proud of the way we swept all this information into the scripts and made sure there’d be revelations in every sequence.

Your knowledge of wildlife must be encyclopedic. Did you learn anything new while making Super/Natural that you didn’t know before?

I’m a big fan of lizards I used to keep geckos when I was young, my son keeps lizards, and I thought I knew everything about them. But then one of our researchers found an incredible story about the scuba lizard, who hides from predators underwater by trapping air bubbles under its scales and channeling them to make this kind of scuba bubble on top of its head. The scuba lizard can breathe from this bubble for about 20 minutes until the danger’s passed. I thought I’d seen it all, but I’d never seen that.

For more stories on what’s streaming or coming to Disney+, check these out:

“Andor” Creator Tony Gilroy’s Intriguing Advice For His Team About Their “Star Wars” Series

“The Mandalorian” Reveals First Images From Season 3

“The Mandalorian” Season 3 Trailer Reveals Mando & Grogu’s Return to Mandalore

Featured image: An African fish eagle catches a fish. (National Geographic for Disney+/Joe Hope)