From “Moana” to “Lupin”: How the Tool “VoiceQ” Does Dubbing Right

It’s all about “lip flap” when it comes to quality voice dubbing for movies and TV. Voice actors make their living by synchronizing dialogue to the micro-movements that happen when on-screen characters open and close their mouths, AKA lip flap. Imprecise voice work results in cheesy-sounding foreign language adaptations. But voice dubbing, done right, has helped propel series like the Korean language Squid Game, Spanish-language Money Heist, and French-language Lupin to hit status in the United States.

According to dubbing mogul Steven Renata, foreign language entertainment surged during the pandemic when Netflix and other streamers started importing more content from overseas to appease viewers who’d burned through existing English-language inventory and wanted something new to watch. Meanwhile, animation fans in Europe and Asia sustained their appetite for foreign language versions of Moana, The Lego Movie 2, and other features. All these exports and imports helped situate New Zealand-based software app VoiceQ as a key player in the burgeoning world of dub.

VoiceQ, when paired with a desktop audio workshop like Pro Tools, enables voice actors to record dialogue from their home studios as video content unspools across their computer screen. “It’s like Karaoke for voice actors,” says Renata, managing director for VoiceQ. Speaking to The Credits from his Auckland office, Renata defines “Rythmoband,” praises cloud-based collaboration, and describes why technically perfect translations always need to be tweaked.

In voice dubbing, timing is everything. How does VoiceQ make it easier for actors to match their dialogue with characters speaking in a foreign language, taking Korean-language Squid Game as an example?

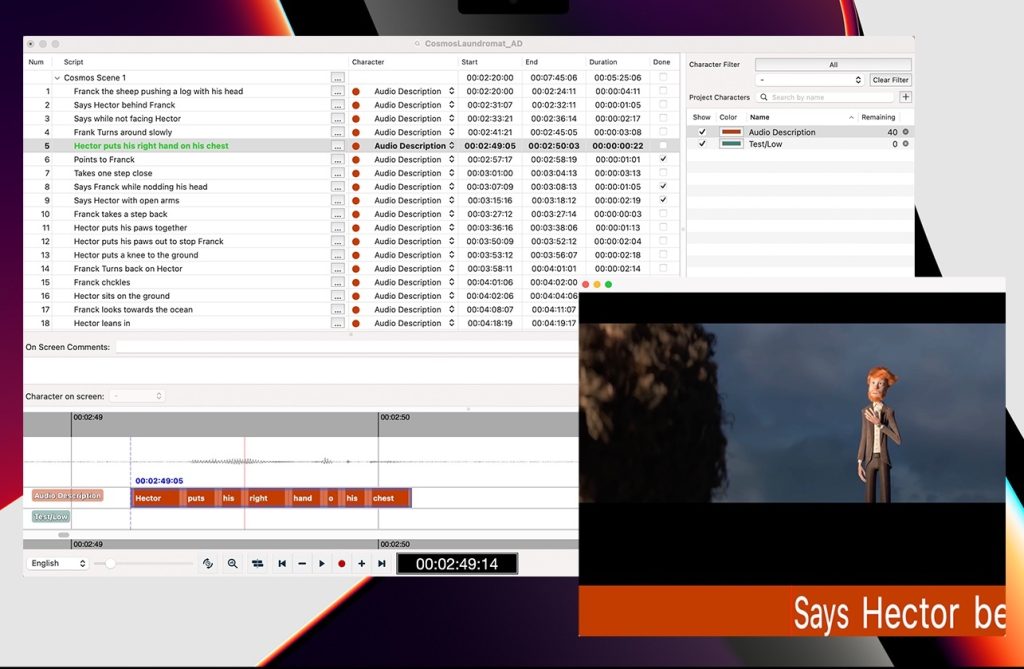

The workflow begins when the original Korean language script gets translated verbatim into English. It’s imported into VoiceQ. However, each line is almost always going to be slightly longer or slightly shorter in English so if you recited the strict translation, you’d have to say it a little bit slower or faster and the lip flap wouldn’t fit. Therefore we need to adapt the translation to make the lips match, and that’s where the artistry comes in. If you’re the adaptor, in the top right-hand corner of your screen there’s the video of a Squid Game episode. To the left of that is the translated script line by line and next to that is the adapted script. Let’s say line two is a little bit off. As the script adaptor, you might put in a word, add a pause, or take away something. You can quickly make a change, check it against the video that’s playing on the screen and if it’s okay, you move on to the next line. Adapters are under a lot of pressure to get the project out the door, and our VoiceQ software makes the process faster.

Next, this adapted script, which should be lip-flap perfect, goes to the voice actor?

Yes. Markers give you a sense of when to inhale, exhale when to lift your or drop your voice because there are so many nuances in the rhythmoband as we call it.

What’s a rhythmoband?

It’s a really old process where the [translated] dialogue used to be hand-written onto a film strip that ran with the original film. VoiceQ provides this high-tech modernized version of that process.

So the voice actor sees the words on the computer screen flowing from left to right …

Or right to left if it’s Arabic, or top to bottom if it’s Japanese.

Can the actors customize the program to get, for example, a three-second prompt ahead of where they come in?

Yeah. Some actors like a lot of pre-roll, others are like, “Just give me two words prior and I’m good.” You can adapt VoiceQ to suit the actor’s preferences to be in character quicker so you can do voice acting as opposed to voice over.

That’s an important distinction because there’s nothing worse than watching and listening to a badly dubbed show with stiff dialogue that feels disconnected from the characters.

There are a lot of nuances that are required for good dubbing, and our interface allows that.

In 2016, you joined VoiceQ as managing director. How has the dubbing marketplace changed since then?

About three years ago Netflix did research and found that people will watch a series with quality dubbing all the way through, whereas if the show is subtitled, people tend to check out. That’s a massive insight. Once you’ve got the public saying “If you dub it the right way with the right voices, we will watch all this foreign content,” that’s when companies shifted their views about this slightly more expensive, slightly more complex thing. Dubbing exploded and then, just to put a bit more fire under it, along comes Covid.

How did Covid impact the marketplace?

At some point, streamers had no original content left because nobody could go anywhere to film [new projects]. When the global pandemic burned up the original libraries. There’s only one way out: dub [foreign language shows].

Did this upturn in interest inspire you to upgrade the product?

Over the course of eight months, we went to all of our clients, 50 around the world. We did webinars, we did focus groups, and we took feedback from anybody and everybody. In the space of 400 days, we made 100 product enhancements. That’s one upgrade every four days. People couldn’t believe that one, we actually listened and two, we produced what they asked for.

Do you see VoiceQ tapping into this trend of remote working, where people no longer travel to physical facilities to get their work done?

Studios spent millions on brick and mortar spaces. When Covid started to ease off, they want to go back to the physical studios but, having gone through the pandemic, when they couldn’t get voice talent into the studios, they realized there is a place for cloud technology in certain cases. For example, maybe there’s a really good voice actor down in New Zealand they only need for seven or eight lines, so let’s just do it remotely. Bang!

Same with Automatic Replacement Dialogue for a live-action movie?

Absolutely. Maybe there are 20 lines in a movie the studio needs to do pick-ups for, but the actor has flown off to China to work on his next project. They can use our cloud-based technology and have the person do the ADR as a remote. We license cloud applications as well as native [desktop] applications, which allows directors, actors, writers, and editors to work on the same version of the project. If one person on the team drops the bat, you get a sh*t result. We really want to honor the original content and the authenticity of voices, so all those people need to be looked after.

In New Zealand, the majority English-speaking population exists alongside this vibrant indigenous Māori culture which has its own language. Did your Maori heritage inform the way you connected with this tech platform that helps dismantle language barriers?

I have Māori ancestry through my father — my mother’s ancestors are from Scotland and Ireland — so I have a very real appreciation for First Nation languages. And having traveled a lot, I realize how much people appreciate hearing content in their own language. In the television and film world, you can now do this localization of content much faster without having to worry about the lip flap. That’s what created this boom in dubbing, and we happened to be in the right place at the right time.

Featured image: Omay Sy is ‘Lupin.’ Courtesy Netflix.