The Vietnam War Sound Designer on Enhancing Emotional Memories of the War

The Vietnam War was a harrowing conflict with ramifications that spread far from the fighting. It was the most divisive war of the 20th century that haunted veterans and civilians alike for decades. Cameras captured the brutal battles with unprecedented access. Piecing together hundreds of hours of archival footage and interviews with survivors, celebrated documentarians Ken Burns and Lynn Novick assembled an intimate portrait of the horror and humanity of the war. The Vietnam War created an illusion of immersion that demanded reconstruction of scenes with no or low-quality sound and gripping witness accounts. Sound designer Jacob Ribicoff reconstructed the ambiance of the raw recollections and video remnants from the time.

Of the ten-episode series, Ribicoff served as music editor as he has on several Ken Burns projects since 2000’s Jazz and helmed roughly a third of the sound design. His work on The Vietnam War included weaving together a variety of sources of footage in a consistent style. Ribicoff’s task was to paint with a library of sound that illustrated first-hand accounts from the era.

“If you have a grainy piece of footage like the footage that came from the North Vietnamese side, it was like WWI footage,” Ribicoff described. “It’s black and white. It’s really degraded. The footage that comes from the American side is really amazing. Putting all of those sounds and smudging them out, doing things with the sounds or just playing them very quietly or mixing them at a low level. Those are all kind of techniques that we’ve all learned over the years so we were able to put to good use for Vietnam.”

A misconception of casual observers is the idea that documentaries are self-contained. Well told, a documentary will reach beyond found footage and is able to provide new layers and details previously unexplored. In reality, it takes more than live footage of an event to tell the story. In the case of The Vietnam War that includes crafting an audio tapestry to recreate events from decades ago.

“The breakdown would be that rarely did any of the archival footage have sound that was usable,” Ribicoff said. “A lot of it is recreation. Obviously, that is where the foley and the footsteps and the movement of walking through the jungle and then setting the atmosphere with the night insects, the air, the birds during the day on the rice paddies. Then there’s that whole category of the helicopters, all of the weaponry, the guns, the bullets. Then the voices in terms of the Vietnamese voices, but there were obviously also American troops.”

The filmmakers called on dozens of veterans, journalists, and civilians to provide witness accounts, but many voices are lost to history. Thousands of lives that were affected by the tragic fallout of the war were represented in new recordings.

“Unlike so many documentaries, we were working with foley and we went out and did recordings of voices,” Ribicoff explained. “We had a two to three-day recording session of Vietnamese voices that we did here in New York City. That was so valuable to us to have those voices – male, female, all different ages. We played different sections from something as intimate as whispers in the jungle to something as huge and massive as the fall of Saigon and getting crowd and hysteria and things like that.”

The spoken words in the series were so moving, but the sound design had an emotional resonance where words end. Visuals could help orient the viewer and reveal harrowing moments, but sound goes even farther in the ability to transfer an emotion. What we hear can be a great signal of distress, fear, or grief.

“Just adding another dimension that we hadn’t really done in previous documentaries, which is to go to this more emotional abstract sonic realm of trying to create a representation for emotional things,” Ribicoff described of the value of intermixing foley into documentary sound design. “For very subjective feelings and trying to use the sonic language to convey both the veterans’ memories of their experiences and to convey the physical, mental, emotional distortion, the PTSD, the actual feeling of being in battle or being a POW. We had that great opportunity to go into that sonic realm.”

The finished product as an audience member is nearly seamless. The sound is a helpful guide that feels so natural. However, Ribicoff experiences the footage without sound and has to make decisions on how to enhance the scene. He observes what is missing on screen that he can add to complete the story and finds ways to fill the gaps.

“You’re certainly getting clues visually from what you see in front of you,” Ribicoff explained. “The first layer would be what are we literally seeing in front of us? Let’s try to duplicate that. A lot of the footage is so dynamic and unintentionally abstract. There are night shots and all these flares going through the sky at night. There’s almost a poetry to that footage. Or handheld cameras where there’s chaos and you have someone who is with a battalion holding a camera and a bomb lands and that person is suddenly scrambling for safety and the camera stays on. You have this wild emotion and blurring and all of that stuff. Suddenly that gives us license to do equivalent things with sound. That’s what made the project so much fun. We had that license to use echo, tones, and try to push ourselves to find sounds and make sounds.”

The entire series is filled with gripping untold stories and personal accounts. One subject, John Musgrave, is particularly striking and Ribicoff was exacting in honoring his story. Musgrave’s account is tense and detailed and the sound design immediately transports us into his mind.

“He is funny and very emotional,” Ribicoff said. “He is basically telling a story of being on a listening post in the middle of the night in Con Thien. He is just a man sitting telling a story. That was a section that I got to do the sound design on and it gave me an opportunity to really make that story. It’s already really evocative just in his telling, but he pauses and then the picture editors begin to cut footage in as he’s telling the story of the things he’s talking about. Taking helicopter blades and mixing that with a heartbeat sound and doing something to both sounds and then taking that sound and having it fluctuate and accelerate and then slow down and speed up as he’s moving toward the climax of his story. Those were ways of enhancing or adding more dimension to the story.”

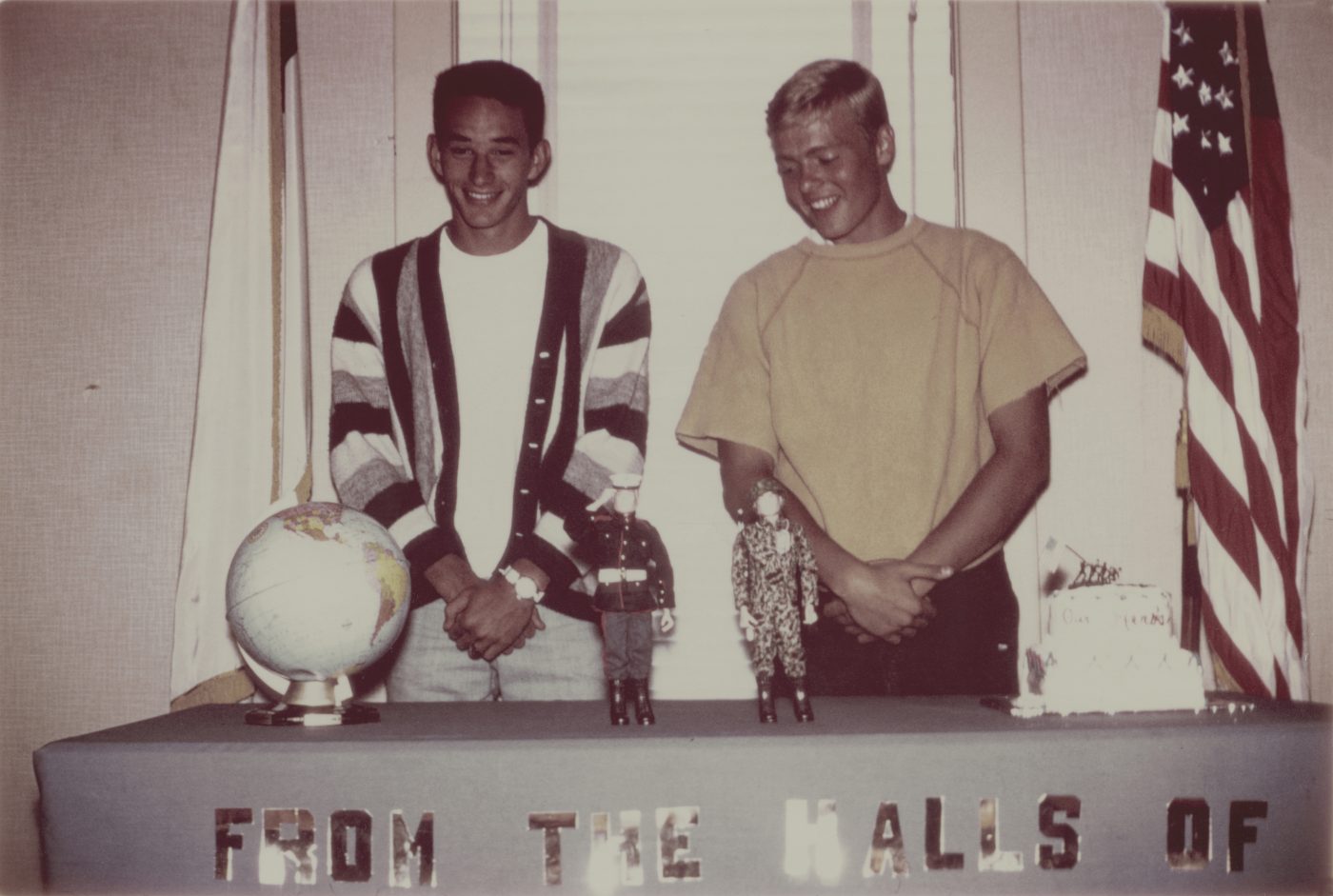

Musgrave (striped sweater) and Jay VanVelzen at the MYF surprise going-away, before they left for Marines August 30th. Courtesy: John Musgraves

Ribicoff has worked on a variety of documentaries and narratives, but he says that there’s a universal guide to crafting the sound on any film. Utilize whatever sound best serves the story.

“Documentaries are storytelling,” Ribicoff said. “The approach ultimately is about storytelling and what are we going to do with sound that is going to deepen the viewer’s experience and convey things that go beyond the visual and beyond what you see. In the end, it’s about storytelling.”

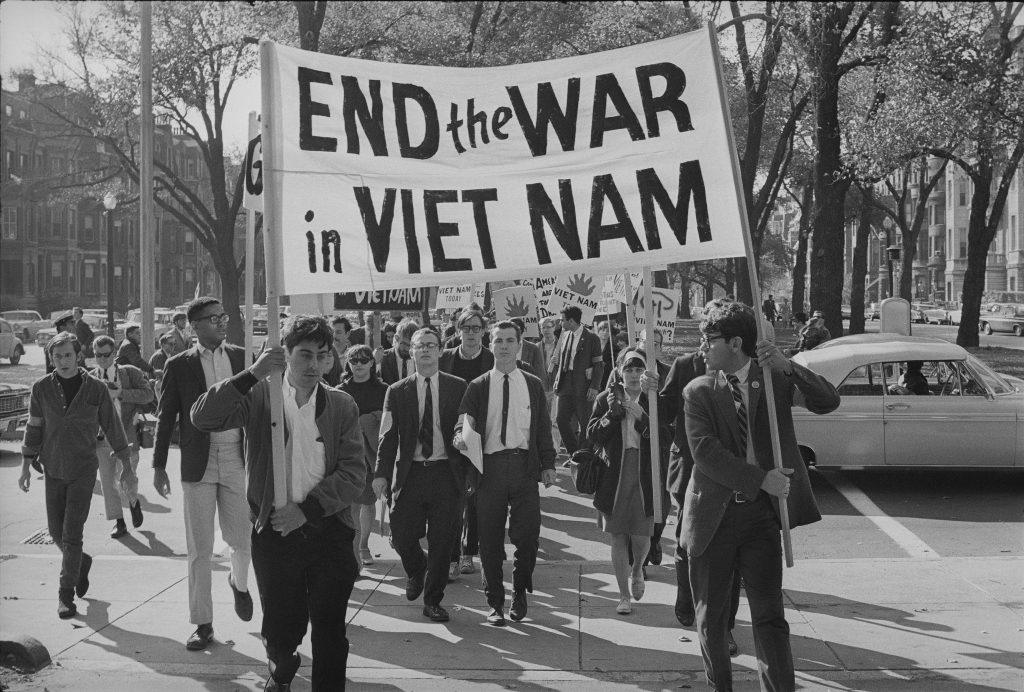

Featured Image: College students march against the war in Boston. October 16, 1965. Courtesy of AP/Frank C. Curtin