How Director Kevin Macdonald Uncovered Bombshell Allegations in his Whitney Houston Doc

Before he shot Whitney, Scottish documentarian Kevin Macdonald did not consider himself a particularly avid Whitney Houston fan. The Oscar-winning director (One Day in September) preferred The Clash back in the day when Houston dominated pop music with her unmatched vocal power. “I was not into that kind of mainstream poppiness,” he says. “At the time you couldn’t avoid her music, but it was kind of unhip to like Whitney Houston.” So when Houston’s family asked Macdonald to make a film about the troubled diva a few years after her drug-related death at age 48, Macdonald gravitated to the mystery more than the music. He recalls, “Whitney’s agent Nicole David loved Whitney, but never understood why she ended her life the way she did. Nicole wanted me to find out why.”

Macdonald faced a formidable challenge: Houston generally kept her private feelings to herself. “Whitney didn’t give many interviews and the ones she did do were not very revealing,” says Macdonald, who profiled Bob Marley in 2012 documentary Marley, and steered Forest Whitaker to an Academy Award in fact-based drama The King of Scotland. “She didn’t keep any diaries. She didn’t write songs. You’ve got very little to go on but at the same time, I was fascinated by that void. I wanted to dive into it and figure her out.”

Archive producer Sam Dwyer spent 18 months organizing material from the Houston estate supplemented with previously unseen home movies shot by members of her entourage. But the key insights in Whitney came directly from members of Houston’s family. During early on-camera interviews, relatives described Houston’s childhood as “idyllic.” Macdonald persisted with numerous follow-up sessions and Houston’s brother Gary finally opened up. “The first time I met Gary, I didn’t like him at all because he seemed quite aggressive,” Macdonald recalls. “By the fourth interview, I’d come to sympathize with him. As we talked about his struggle with addiction, Gary said he’d been abused by a female relative when he was a child. That was a complete shock to me. By the end, people in the family told me this [filmmaking process] is the therapy they should have been doing years ago.”

Only about half of the 70 people interviewed by Macdonald made the final cut, and several of those subjects deflected his questions. “I wanted the audience to experience the flavor of what I went through in making the movie, which included confronting various people who were not necessarily telling the truth all the time,” he says. “I was also frustrated by people like [Houston’s ex-husband] Bobby Brown, who wouldn’t talk to me about anything of substance.”

In between his expeditions to the U.S., Macdonald immersed himself in footage of Houston, on stage and off. He says, “I got this feeling about the way she carried herself that she’s not at ease in her body, not sexually at ease, even though she’s so beautiful.’ It felt to me like I was looking at somebody who may have suffered trauma in childhood and reacted by closing herself off. I recognized that [body language] from people I’ve met in life who have suffered similar things.”

Another clue presented itself in the form of a puzzling radio interview conducted by a British radio journalist. “He asked Whitney what made her angry and she answered ‘Child abuse makes me angry.’ I thought, ‘That’s so weird, of all the things she could say, why would she say that?”

Whitney from The Credits on Vimeo.

Two weeks before Macdonald finished cutting Whitney, he re-interviewed Houston’s close friend Mary Jones. “She knew Whitney probably better than anyone and Mary wanted to talk about this elephant in the room. At the very last minute, this interview with Mary really changed my understanding of Whitney. Making documentaries, you never know where you’re going to find that valuable little piece of the jigsaw puzzle. This was a classic example of getting something you weren’t expecting.”

The documentary’s bombshell allegations reveal dark Houston family secrets, but in the course of making Whitney, Macdonald also came to appreciate her brilliance as an artist. “I think Whitney’s inability to express all these things that were troubling in her childhood is probably why she was such a great singer,” Macdonald says. “At her best, she affects you like a shot of adrenalin into the heart. She expresses all these complex feelings in what might seem like a fairly simple song. That was Whitney Houston’s genius.”

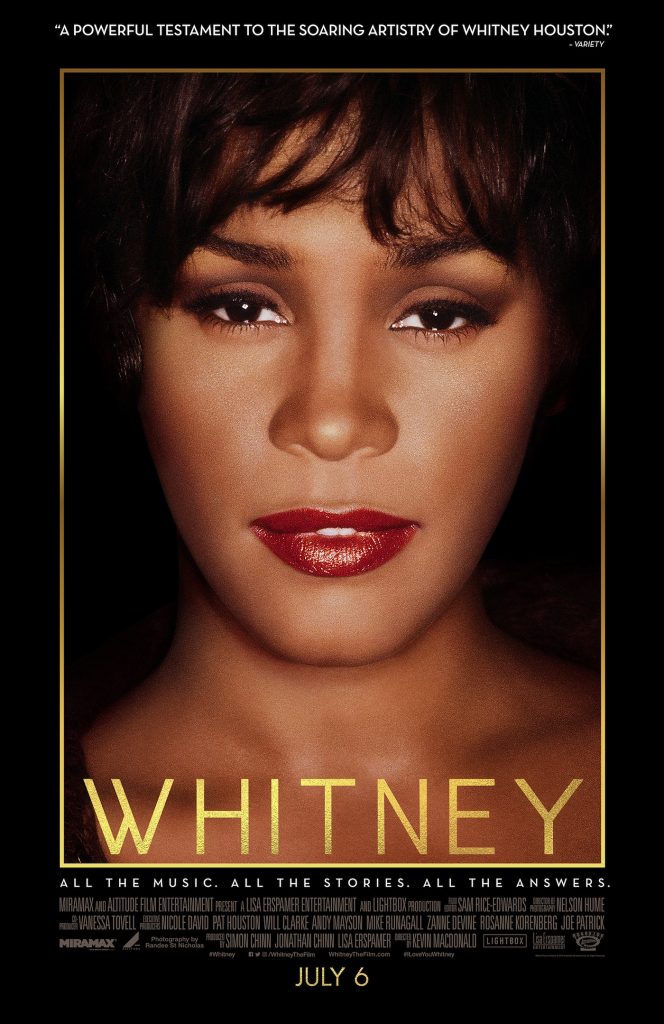

Featured image: “Whitney.” Courtesy Roadside Attractions