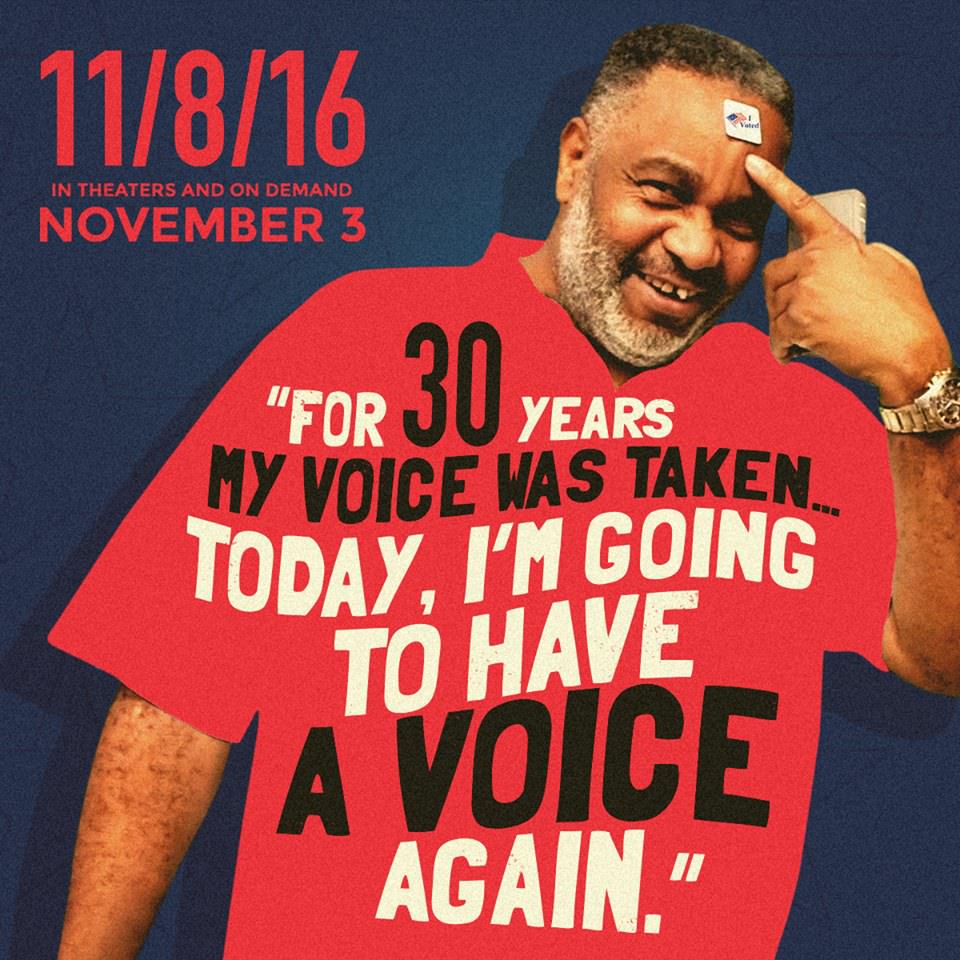

Jeff Deutchman Thinks Everyone (Especially Liberals) Should Watch his Election Doc 11/8/16

In the fall of 2008, documentary producer Jeff Deutchman had a last-minute idea: an omnibus movie that would capture election day. He sent requests to his filmmaker friends, all of whom were Obama supporters, and ended up with an account that had a relatively narrow focus. Eight years later, he started planning sooner, and threw his net wider. The result is 11/8/16, which The Orchard will premiere in theaters and on iTunes and Amazon Video today, as well as VOD platforms. Here’s where to find it.

The documentary interweaves 16 narratives, filmed from Massachusetts to Hawaii and directed by 14 solo filmmakers and two duos. Included are Donald Trump supporters, Hillary Clinton partisans, an Evan McMullin campaigner, and one guy who didn’t vote. The candidates and their inner circles appear only in the distance, but there are two sets of media observers, one at the Los Angeles Times and the other at WHYY, the NPR affiliate in Philadelphia.

Deutchman, who describes himself as a New Yorker who lives in L.A., talked to The Credits while visiting Washington the week before the movie’s release. The interview, which has been edited for length and clarity, began with the suggestion that some people may not want to relive the events of Nov. 11, 2016.

Sure. I’ve heard that. My view is, I don’t think it’s healthy for us to bury our heads in the sand. That comment would commonly come from the liberal side. so I’ll address it from the liberal side. I don’t think it’s too soon to try to understand the country that we live in, and to try to do a postmortem on how this happened. I think it’s too late. We should have been thinking about these things earlier. So I understand if there’s reluctance, but I think it’s really vital that we confront these things head-on.

11/8/16 is your project, yet you’re listed as curator and producer, not director.

This is an unusual kind of film. It consists of segments that were directed by different people, yet I oversaw the entire process. People have argued that I should be listed as the director. I decided not to do it that way. It’s semantics, in my view. My role was to oversee the entire project from pre-production to post-production. But at the same time I wasn’t filming, and I wanted to pay tribute to the work that all of those directors did.

Fifty stories were shot. So one of your jobs must have been eliminating whole storylines.

Yup.

Did you do that based on the appeal of the individual segments, or on the way the pieces fit together?

Both. The filming strategy was to stack the deck with as many possible stories as we could, so that we had a lot to choose from. And it worked. It was a good problem to have, but we had to make some really painful decisions. Some of it had to do with, obviously, who’s compelling. Some of it had to do with not wanting redundancies, even superficial ones. Having two people from the same state who look similar. But also substantive redundancies — what their story was, what their arc was. And really wanting to make sure the subjects in the film are complementary, and that each represents something distinct about America.

Did you identify some of the subjects, or was it all the individual directors?

It was a mix, but I would say most of the ideas for subjects came from the individual filmmakers. I had to approve it, ultimately, and sometimes there was back-and-forth. They might have several ideas, and I would choose one. In the case of the L.A. Times, that was actually something I set up, and then brought on Daniel Junge to direct it.

Most documentary filmmakers have a reservoir of potential subjects they’re interested in. In some cases, these were subjects who filmmakers had worked with in the past or wanted to work with in the future. Or just sort of had in the back of their head. Those preexisting relationships came in handy, because when you’re making a documentary, you want the filmmaker-subject relationship to be one of trust, and that takes time. We only had one day, so I really leaned on some of these preexisting relationships.

When you’re asking the filmmakers for only one day, does that make it an easier pitch?

Yeah. It would have been harder, availability-wise, and also more expensive, to get people to devote themselves for longer than a day.

Could some of the footage that’s not in the film be released in some other form?

Yeah, it could. The Orchard owns all of that footage, and we’ve been talking about trying to make use of some of it. There really is a lot of great material that didn’t make it into the film.

Did you have strong guidelines as to what each segment would be?

Very little. We knew who the subjects were going to be, and as part of that process, we asked most of the subjects to give us a sense of what their day would look like. Beyond that, nothing else. The guidelines I gave the filmmakers were: Shoot your subjects from the beginning to the end of the day. Always skew verite when possible. It wasn’t strict verite; I wanted them to be comfortable asking questions when appropriate. But whenever it was possible to capture something completely candid, that was always preferred.

We had no way of knowing what the outcome of the election would be, and how that would dictate the course of the day for a lot of the subjects.

You must have some assumptions.

I did. I assumed Hillary Clinton was going to win, as a lot of people did. People don’t believe me when I say this, but as it relates to the movie, I didn’t dwell a lot on the outcome. Because I knew that regardless of who won, the movie could have been a million different things.

If Clinton had won, I still would have had to figure out what the movie was, based on the footage. It wouldn’t simply have been the celebration of the first female president. That would have been part of it. But there would have been … something else, that I would have had to figure out. There’s always an element of not knowing what these movies will be, so I just don’t dwell a whole lot on the outcome. I do as a citizen, but not so much as a filmmaker.

How much footage did you have of each of the subjects?

It ranged from everything from four hours to 12 hours. Some people never stopped filming; some people did. In total, it was probably 300 hours.

You didn’t watch it all?

I watched, basically, all of it.

So you were part of the editing process.

Yes. I wasn’t one of the hands-on editors, but I was overseeing the process. I was watching all that footage and making the judgments about which stories made it into the film.

How long is the average segment?

The movie’s 104 minutes. Divide that by 16. I think it’s probably eight or nine minutes.

So that’s a lot of cutting.

Yes. There were points in the process when I didn’t think it was going to be possible to make a film less than three hours. Or two-and-a-half. And it kept getting lower and lower until at one point, I realized, OK, we can make this digestible, feature-length.

Was that a result of pulling out whole threads, or just from boiling down the ones you were committed to?

A little of both. There was only one subject who was originally in the film that we cut out. WHYY’s Dave Davies we played with a little bit. Originally, he was introduced as a fully fledged character, the way all the others are. Then we figured out that there was a way of using him that’s almost like a play-by-play announcer for most of the film, and then kind of introducing him toward the end. Little things like that helped with running time. Other than that, it was just losing moments here and there.

Were there more news-media characters in the mix originally?

No. We tried to get [Infowars.com’s] Alex Jones. But that didn’t go anywhere.

What’s most important thing to you in what you’re showing?

It’s the individuals, and an opportunity to spend time with a diverse cross-section of Americans behaving as they would if the cameras weren’t there.

Making this movie, I was watching all that footage — and having this weird one-sided conversation where people were talking to me and I wasn’t able to respond, which was often maddening, What I learned was there’s value to listening without being able to respond. While speech is obviously an important right and freedom in our country, it’s a little overrated as an obligation. Especially with social media, I think we’re all *expressing* ourselves constantly, 24-7. Sometimes it’s valuable just to sit back and digest what other people say. Not ceding the floor in any way, but just so they can feel heard and you can properly understand where they’re coming from.