Historian Deborah Lipstadt on Inspiring the new Film Denial

Deborah Lipstadt's History on Trial: My Day in Court with a Holocaust Denier recounts a deadly serious farce: Almost two decades ago, the Emory University professor found herself in a London court, defending herself in a libel case brought by David Irving, a self-styled historian whose books take a pro-Nazi view of World War II and the genocide of Europe's Jews and other victims. The book was recently republished under the title Denial, which is also the name of a new movie based on it.

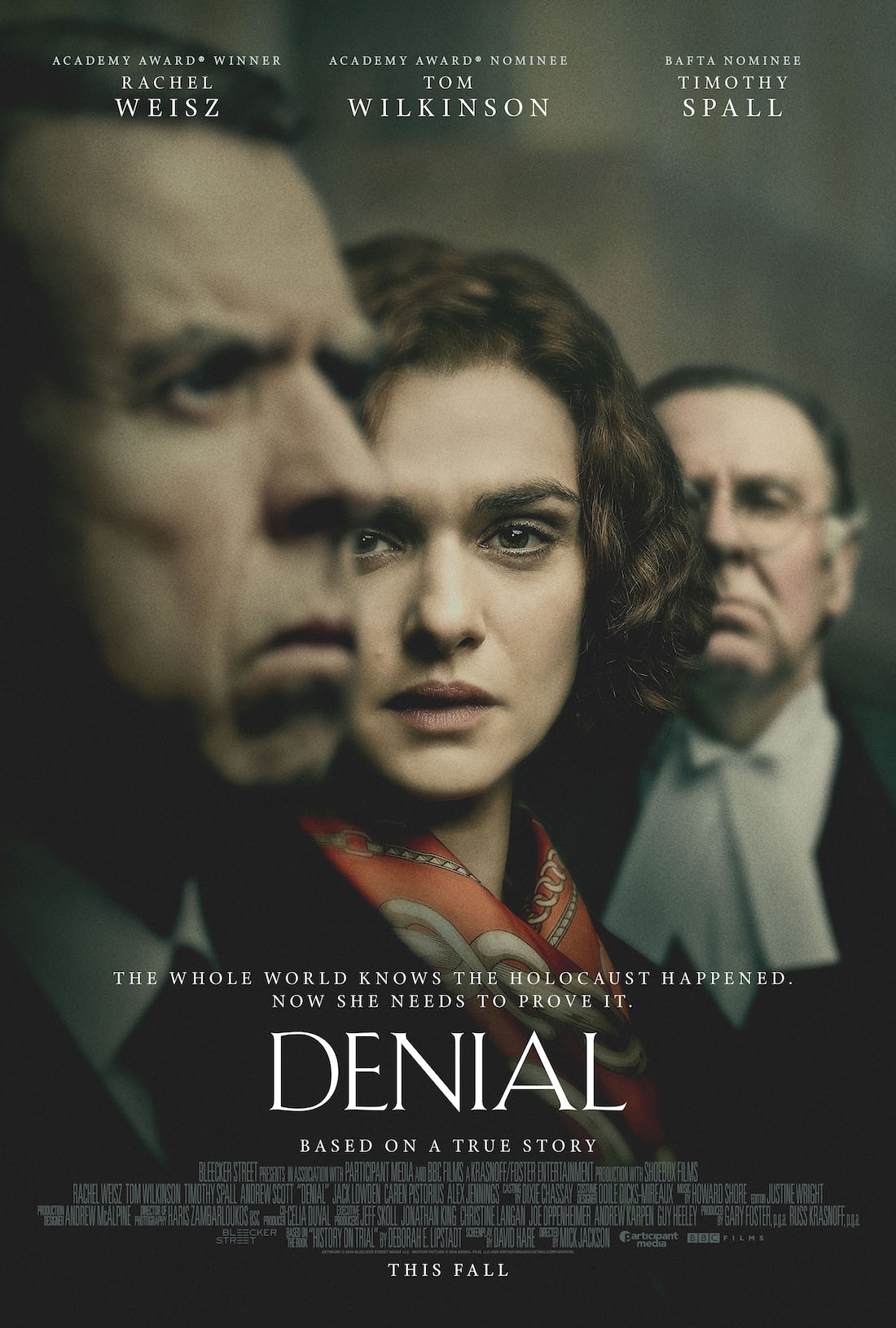

The drama was scripted by David Hare, who Lipstadt always identifies by his full name to distinguish him from David Irving, and directed by Mick Jackson. Rachel Weisz plays Lipstadt, a slimmed-down Timothy Spall is Irving, and Andrew Scott and Tom Wilkinson have the roles of Lipstadt's British lawyers, Anthony Julius and Richard Rampton.

Under British libel law, the burden of proof is on the defendant, not the accuser. Lipstadt's attorneys devised a strategy that kept both her and any Holocaust survivors from testifying. Lipstadt had to sit and watch other historians make her case. It's a curious premise for a courtroom drama: The central character never gets her big speech on the witness stand.

Lipstadt recently visited Washington to discuss her book, her experience, and the film. Her interview with The Credits, which has been edited for length and clarity, began with her explanation of why she decided to promote Denial.

"I'm very pleased with the movie. I would not be here otherwise. I would not be doing this for the fun and the glory. Look, the movie I would have made would have been four hours long. Maybe the short version would have been three-and-a-half hours. There are portions of the story that I would love to have been in there that aren't. But I think they did a terrific job. I think that David Hare wrote a brilliant screenplay. Mick Jackson hewed very close to the truth in presenting what went on. And I think Rachel Weisz's depiction is just — beyond words."

You commend Hare's script. But the courtroom dialogue is entirely verbatim.

Right. It comes directly from the transcripts. David Hare did that for a number of reasons. First of all, that way you couldn't be accused of putting words in David Irving's mouth.

But he saw a bigger issue, and that's what convinced me he was the right person to be doing this. This is a story about truth. And if you're telling a story about truth, you can't then say, "It's sort of like what went on in the court. We had to change it a little for dramatic license." Then it's not about truth. He understood the constraints.

We have a video of what happened at the press conference, and I gave that to both David Hare and Rachel. Rachel watched it very closely. It happened. So if it's in there, it happened.

If David Hare were here, he'd look at that poster for the movie and ink out "based on." Because he says, "It's not based on. It is a true story." Of course, when I got the call from Anthony about the verdict's coming down, I wasn't out jogging with my dog. I was inside my office. But the movie is very much close to the truth.

The first time, you had to sit there and watch. It was all about you, and the most important subject in your life, and couldn't say anything. And the second time through, you had to do it again.

That's very astute. It dawned on me one day when I was on the set. Everybody was running around. Everybody had a job. When Mick yelled "cut," everybody ran to check Rachel's hair, Tom Wilkinson's tie, or whatever. And I would sit there watching. I had nothing to do. And then I said, "This is a metaphor for the trial. It's my story, but I'm an observer."

It was an interesting experience in that way. It was act of denial. I think that if I hadn't had so much faith in what they were doing, it would have been much harder. They were happy to have me there. Rachel in fact wanted me on the set, especially at the beginning. She said, "I like your energy. I like having you there." She would turn to me and ask, "Tell me you how you say certain things." She would e-mail me and ask me to record certain scenes, so she could get my inflection right.

As the filming went on, and she more and more got into the role, she would think she was me. She said to me, " I would look up and I would say, 'Who's that redheaded woman over there? That's not Deborah Lipstadt. I'm Deborah Lipstadt!"

Rachel Weisz stars as acclaimed writer and historian Deborah E. Lipstadt in DENIAL, a Bleecker Street release. Credit: Laurie Sparham / Bleecker Street

How did she become you?

It wasn't just a matter of copying my accent. And of wearing some of my scarves and a copy of the ring I'm wearing now, and which I wore at the trial.

It was, "How were you feeling before this moment?" In fact, on the day she filmed the scene where Irving interrupts my lecture, I was in Barcelona at a conference. She called me early in the morning, and she said, "Tell me what you were feeling." And I told her, "I was like a deer in headlights. Because I was totally blindsided. And I'm not used to being blindsided. I didn't want to get into a shouting match with him. But I saw these students sitting there, thinking, 'maybe there's something to what he says.' So it was a very distressing moment."

So she said, "OK, thank you." And then when I saw how she played those scenes, there is that deer-in-headlights look.

There's a discussion in the film of which accent it is, Brooklyn or Queens.

Here's what the story is. I started out on the Upper West Side. When I was about five years old, we moved out to Queens. I spent the next 12 years in Queens. Then we came back to the Upper West Side. So it's a mix of the two.

Before I first spoke to Rachel, she had just signed on, and she had listened to hours of me on the Internet. She said, "David Irving says you have a Brooklyn accent. Sounds to me more like Queens." So I said, "You're right." So that's how it became Queens.

Then I was having coffee with Rachel after the movie was finished, and I told her my family was mad at me that I said Queens and not Upper West Side. And she said, "Why? Is that more aspirational?" And I said, "No, it's more intellectually interesting." We laughed at that.

What convinced you that this team was right for the adaptation?

In the last conversation I had my with the two producers who originally optioned my book, Russ Krasnoff and Gary Foster, before I gave them the green light, I said, "This story can't be fictionalized. You can't have, during the ninth week of the trial, someone go up to their grandfather's attic, find the plans for the Holocaust, and bring them in, and say, 'Look! We found the plans.' It didn't happen. They said, 'We get it.' Then when they brought in Participant Media and BBC Films, I was further encouraged. Because they are two companies with great reputations.

Then they brought in David Hare. I met with him four or five times in London before he decided to do the script. Then he came to Atlanta and followed me around for several days to see my house, my friends, where I taught, my office.

He wrote a summary of the issues. He was obviously beginning to conceive how he would construct the screenplay. On the cover, he put a quote about truth from Bertolt Brecht's Galileo. Before I even read the document, I said, "He gets it."

Mick Jackson comes out of documentary film. He's done lots of feature films, L.A. Story, The Bodyguard. But he also did Temple Grandin, the biopic with Claire Danes as the autistic woman who became a successful scientist. That's what sold me. Not only did I know Temple Grandin, but I really liked the film.

That's what really sold me. But I liked Bodyguard.

You've said that the Holocaust is one of the most documented atrocities of all time. That makes it a strange subject to attempt to deny.

I say to my students sometimes, when I'm talking about Holocaust denial, "For deniers to be right, who has to be wrong?" Well, the people who would be wrong are the victims. They all vary their story, but as Salman Rushdie quoted a British policeman in his book about his time in hiding, "If everybody has the same story, it's not true." So survivors tell slightly different versions.

But we have the survivors. We have the bystanders. The people who saw the trains going into the camp day by day, and coming out empty. The people who knew their neighbors disappeared, never to reappear again.

And we have the perpetrators. No perpetrator who's been on trial has ever said, "It didn't happen." Even Adolph Eichmann, who was on trial for his life, and if he could proved it didn't happen it would have saved his life. But he didn't say it didn't happen. He said, "I didn't do it. I had to follow orders."

Plus the fact that there are all these documents. Perpetrators describing how they put the gas in the gas chambers.

But along come the deniers and say, "It didn't happen." They turn it into a seemingly logical argument. "We're scientists. We're just trying to revise mistakes in history." Hence they call themselves revisionists. But at its heart is antisemitism. And antisemitism, like any form of prejudice — whether it's racism or homophobia, whatever it might be — is irrational. Don't confuse me with the facts.

It's completely irrational, it's delusional, and it's stupid. These are people who starting with an antisemitic view of the world, and then fitting the facts into that. Their version of the facts. Or they'll take the facts and they'll change them.

You're a historian. And this book is a work of history in a sense, but it's your story. Was that easier or harder to write?

It was the book in which I entered the story. And that was very hard to write. My editor had to keep pushing me — "How were you feeling?" Not so it would become this soppy kind of book. But I couldn't write more of just the history of Holocaust denial, because I'd already written that. It was challenging, but on some level it very satisfying. When it was published, I thought of it as the culmination of this battle. "OK, I got sued. We fought. We won. I've written my book. On to other things."

A couple of years later, it all got woken up again, but I'm very pleased, because it will bring the story to millions of people who had never seen it.

If there's a takeaway for this film, I would say it's three things. One, there's fact, there's opinion, and there are lies. What Holocaust denial is, are lies parading as opinion, wanting to be considered facts. That's what David Irving was all about. "I have a document, and I can show you." When you looked at the document, it never showed what he said it showed.

The second takeaway is, you can't fight every battle, but there are some battles you can't turn away from. And a message to young people — and not just young people — about the need to stand up and challenge things.

The third thing, which really grows out of that, is, if you see something wrong — someone taking a lie and turning it into opinion and citing it as fact — say something. But you gotta do your homework. And on some level this trial was all about doing your homework. Doing that research. Tracing the facts. Showing the misstatements of truth, showing the perversions of truth. And showing it to the judge not once or twice, but approximately 30 times. Making our case with the facts.

Featured image: Rachel Weisz and historian Deborah E. Lipstadt on set of DENIAL, a Bleecker Street release. Credit: Laurie Sparham / Bleecker Street