Cinematographer Crescenzo Notarile on his Emmy Nominated work on Gotham

Whether you’re a fan of movies, television, or music videos, Crescenzo Notarile’s award winning cinematography has permeated nearly every medium of entertainment. Notarile has worked with some of the most iconic directors, musicians and brands in the industry for more than 30 years. He was there at the very beginning of the CSI series, helping to shape it into one of the most watched television programs in the world.

Notarile is now nominated for an Emmy in Outstanding Cinematography for transforming New York into a pre-Batman Gotham. Fox has received critical acclaim for the high quality drama that shows the seedy underbelly of comic fans’ favorite corrupt city, when Bruce Wayne was just a child and Commissioner Gordon was just a detective. Notarile’s work on the series is gritty, imaginative and visually stunning.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6G60EtEo6kM

We spoke with Notarile about the grueling Gotham filming schedule, drawing inspiration from comic books, the irony of advances in TV technology and more.

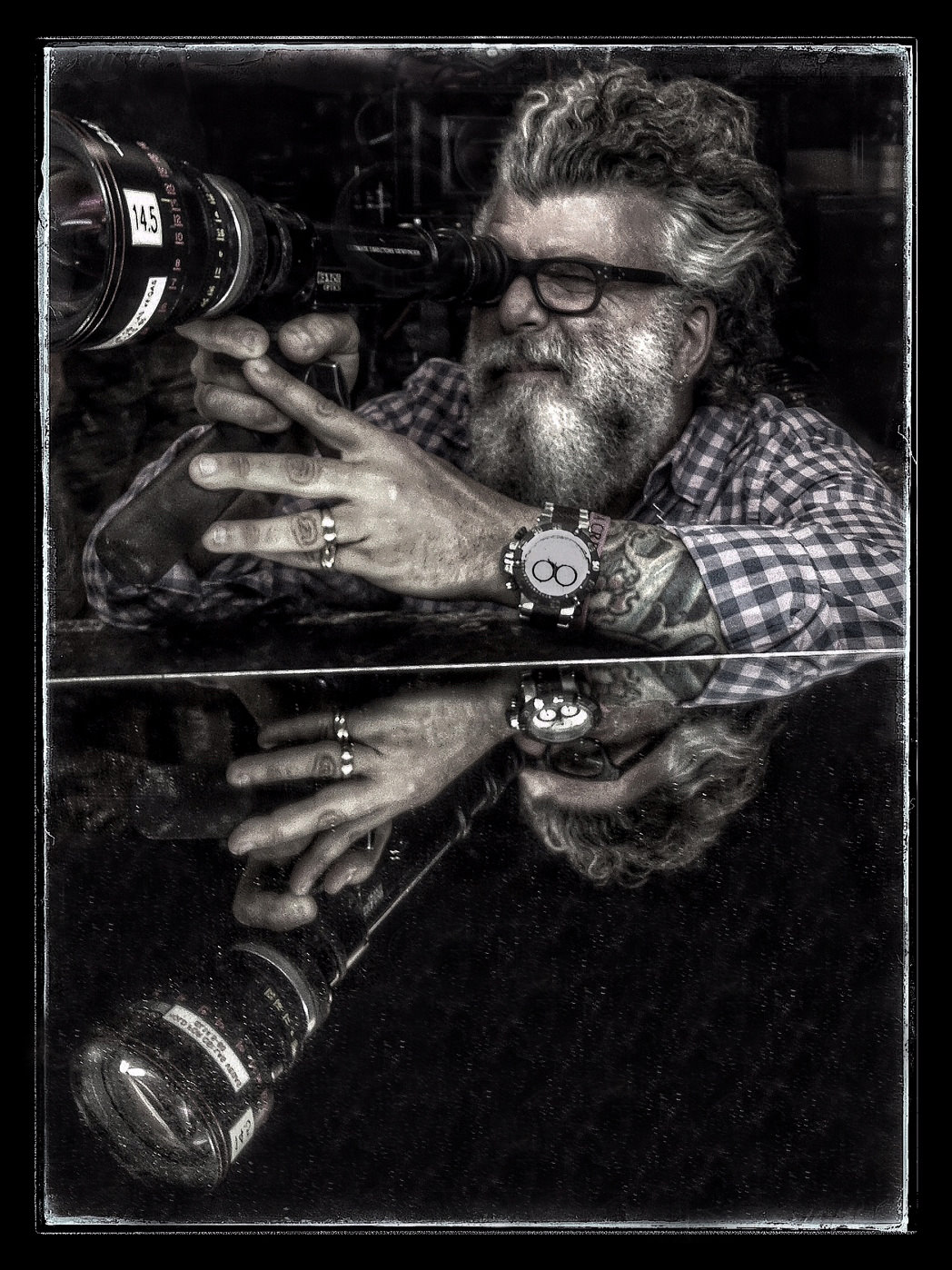

Crescenzo Notarile

Congratulations on your latest Emmy nomination!

I appreciate that. It’s nice to get a little pat on the back from such hard, arduous work. It feels really thrilling, thank you.

You clearly have an incredible body of work having been in the business for over 30 years. What draws you to a particular project?

Being a cinematographer, if it attracts me in a visual way, that’s the first thing that entices me. In the television genre, the most important thing is the story, the content, or the premise of what the show is about. Obviously with a show like Gotham for a cinematographer, it’s very juicy. It’s very appetizing because it’s a world unto itself. It’s not a real world. I’m not lighting things that are very literal or natural. We’re creating our own world. As a result of that, we have an opportunity to think outside of the box and to bring things to the table that we would not normally have the opportunity to do. That’s very exciting. You don’t get projects like that too often. When you’re working in a television genre of course, it’s the story, it’s the prep, it’s all of that that gives you the opportunity to take that project first and foremost. It’s a very juicy project for a cinematographer to be on a show like Gotham because we’re creating our own particular world. As a result there’s no right or wrong. It challenges your imagination to come up with ideas, to come up with looks, to come up with premises that are very different, very eye candy to the audience, in a very unique way that we’re not used to seeing. That’s very difficult in this day and age because the content of television is so enormous and so brilliant out there. To stand out above the few that are around you that are nominated and that are out there in that kind of caliber is very difficult. It’s very rewarding for me to be nominated for such a show at this time, what I call the “platinum age of television.”

You are dealing with characters and a setting that are so iconic to audiences. How do you make the world of Gotham look familiar but unique?

Interestingly enough, it was very intimidating to come onto the project at first because that world of Batman has been created for such a long time in a very wonderful fantastic way that we’re all very accustomed to seeing already. What unraveled a few knots in my stomach was that this was pre-Batman when Batman was a small boy. As a result, we were able to create our own world but with integrity of what has already been done. When you’re doing a project like this and you’re coming onto such a high caliber sort of genre – the comic strip genre which is so large right now. Obviously you try to bring your own personality to the show. So even though there was a history of it, when people come on you have your own personality of look and your own way of approaching matters.

Obviously the world is not created by one person. There are many talented people that we have on our particular team, led by [executive producers] Bruno Heller and Danny Cannon. They created the show by planting those seeds. We as a crew took those seeds and we try to water it everyday in our own particular unique way from our production designing, to our costume designing to our hair and makeup. Now of course our locations. Our location is a character in itself. We shoot here in New York in all of the five boroughs and there’s a reason for that. The character and the texture of all the architecture that we have here to offer. As a cinematographer, we take all of those ingredients and I try to capture that to put it on film.

Why is New York the perfect place to film Gotham?

It’s probably the only place that we could film Gotham because you can see all the ornate and old world architecture that is here. All the bridges and the tunnels and the alleyways. All the night time photography with all the gritty texture that we have here. The hustle and bustle of cobblestone streets, the wonderful early 1900s architectures that we have here. The mansions and the government buildings and places like that. That’s a great pot of ingredients that we have to create our own particular world. It’s interesting when you look at Gotham, no one can really pinpoint where Gotham is. It’s not New York, it’s not Chicago, it’s nowhere in particular. But we use the ingredients from there and embellish it in our own way with production, cinematography and visual effects. We don’t really have iconic buildings in any of our shots, such as the Empire State Building. We try to stay away from those iconic architectures, but we embellish it to give it that texture of our particular world of Gotham.

How do you maintain consistency of the look and feel as you work with different directors on the series?

Each script is a different project in itself. Each script is a different entity, a different beast. The script always drives the project, but it is very important to have a consistent look of what the show is about because of the audience. You don’t want to be too distracting from week to week to the audience because it is like a thread. Like reading a novel chapter to chapter. The look is very consistent and that look is underneath the hands of our two creators. They make sure we maintain a certain look of what Gotham is about. We as cinematographers and crew members follow that look. Of course we put our own personal thumbprints and personalities into that look. That’s why we’re hired in the first place is to bring something of our own hearts and minds to the table. But we’re all together as a family and that’s a beautiful thing. We have 22 episodes per season so theoretically you could have 22 directors. They come in and direct and then they leave to go onto another show. They go in and out. A cinematographer is a constant every single episode.

I imagine you can't be the DP to every single episode.

I do rotate my episodes with a rotating DP because I can’t do them all. One is prepping while the other one is shooting and vice versa because the prepping is so involved and it’s so arduous. It’s as arduous as shooting. There are so many moving parts in doing a show like this that you have to be involved directly with your director to prep the episode. But we have many talented people sitting at a table during the preparation process communicating our visual language to create our own singular vision. That’s what working in television is all about.

Gotham has a very cinematic look. Is it difficult to maintain that level of quality on a TV series?

I’m very proud of that, actually. I’ve been around the block a very long time, shooting for 30 years in this industry. I’ve done everything. I’ve done documentaries, public service announcements, commercials, music videos, motion picture films. The television genre is probably the most arduous genre of them all. When you’re working 14-17 hours a day every day for nine months, you’re doing mini-movies every nine days. An episode is nine days of shooting, seven days of prep. And then the next one starts – seven days of prep, nine days of shooting. You’re doing that for nine months. You can’t slack off at all because of the ratings and the audience, you’re losing all of that. It’s very difficult. It takes a lot of mental, physical, emotional stamina to maintain good work in this genre. It takes a good family around you, good leaders ahead of you. Obviously not everyone is cut out for it. You need a very strong heart. You need to be very strong physically, mentally, emotionally, creatively.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PpTXrddjk54

That sounds exhausting.

The hardest thing about this genre is to maintain that for 22 episodes. That’s why it becomes an extremely arduous genre because it is very difficult to maintain that. There’s no way around it. You have to maintain that because once you slip, the ratings can really drop. They could pull the plug immediately and the show could be canceled just like that. You could be on top one day and the very next day you’re on the bottom. The television genre is so competitive right now that you can’t afford to do that. It takes a lot of great minds and great leaders to keep that thrust. It takes a lot of discipline. It’s very difficult day to day when you’re grinding that hard because it’s not just a technical job. My job can also be very emotional. It’s a very creative medium. You’re dealing with emotions. You’re dealing with feelings. You’re dealing with your own personal forces. Each day you wake up, how you’re feeling and you’re trying to bring that to the table and that’s what becomes very difficult. A lot of television does not have the cinematic look but in this day and age, there’s an enormous amount of television that has that cinematic look. The barometer is so high right now and to create that so called “look” that the audience knows so well is very challenging.

How did you create the visual style that we now see on Gotham?

The seed of the look and that kind of tone and texture was already planted before I walked in. My job was to embellish that and interpret that. My job was to put my personal ingredients into that pot of flavor and to take it that much further. I was on a show called CSI, the original mother ship one in Las Vegas. That had a whole totally different look in itself. That was a beast in itself. When I took this particular project which was the polar opposite, the first thing I did was to pick up a few comic books from the bookstore and just to flip through to see what that world was about. I wasn’t so much of a comic book fan before this show, but now I am because the first thing I noticed when I looked through the comic books was the compositions. The compositions were very unique, strong, angular. They were very artistic in the compositions. They were very graphic, very exaggerated.

As a photographer and a cinematographer, looking at that was very thrilling for me to see. I try to bring that kind of flavor into my personal signature when I came onto the show. Working with the camera operators who are fantastic artists in themselves. I tried to bring a lot of that composition into my work. It was trying to bring in certain colors, certain compositions, certain approaches that were very distinct to the show and thinking outside of the box. I work with a lot of talented crew members who bring a lot to my table to make me look good as well. We’re all one family and have our own unique approaches of looking and our own personal ingredients as artists to bring to the table. It’s not just me, but I work with a lot of talented people. In this particular genre, it’s a very collaborative medium. I work with a lot of talented people and we put all those ingredients into the pot as a singular vision. My job is to execute that.

I bought a big flat screen TV this year, and sometimes it is so clear that it can be distracting. Has changing technology over time affected your work?

Yes, it has. It is very daunting. I think it’s probably why the television genre is so high right now. People are indeed watching a lot of content, a lot of movies, a lot of shows on their giant home HD screens with the surround sound. They can have the opportunity for luxury to sit at home with their personal time to watch these particular shows. Obviously it’s very daunting. The quality and sharpness is magnificent right now and when you’re dealing with your actors, especially your actresses, you’ve got to be very careful as to how sharp and how clear all of that becomes because every wrinkle, crevice and blemish of the face becomes very magnified. As a cinematographer, my job is to protect my actors. To make them look beautiful and larger than life.

When you’re dealing with this kind of technology that we have, it becomes that much more magnified. I mentioned that Gotham has a very cinematic look and one of the reasons is I’m shooting with old vintage Panavision lenses which are a little softer than the lenses that are out there. They’re a little more old world softer lenses. And that’s one of the reasons why this show has a particular look. In terms of my lighting, I’m working with the fusion gels, I’m working with the softer bounce lighting to protect the actors and to be a little kinder to their faces and to give it a little more cinematic, creamier feel as opposed to that hard, harsh 6 o’clock TV news feel where the HD is so sharp that it just doesn’t seem real. It’s very important that we try to keep that cinematic look the way that film once looked. Now that we’re in the HD world, we try so hard to make our HD world look like the film world. It’s so ironic that when you’re working in HD you want it to look like film. We as cinematographers say to shoot film. We all prefer to shoot film. Film has a much more organic quality to it. It’s nice to feel grain, the chemical grain of film as opposed to the electronic pixel of HD. Organically whether you’re aware of that or not, it feels different to the audience, the cinematic look vs. a TV hard look. Cinematographers, we’re not just technicians. We’re also artists. We try to hybrid the two together in our own particular way to create our own cinematic world on this particular show.

How did you decide to become a cinematographer? What film or TV show inspired you to pursue your career?

Very simply, my father was a famous art director in the world of advertising. One of his photographers was the famed Richard Avedon. When I was a small boy aged 4-9, my father often took me to his studio at the advertising agency. I used to watch my father work and these photographers work as well. Whether it was tabletop photography, portrait photography, I used to watch these photographers work. I knew from a very young age. I knew I wanted to become a cinematographer from about five years old. I was taking pictures since I was five and I was developing pictures in my parents’ bathroom. I had a little semi-dark room and I knew I wanted to become a photographer. I was going that route all the way through the beginning of high school and one class, a communications art class, the instructor showed a short film. It was a Twilight Zone episode – “Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.” And this short just totally blew my mind because of the story. I did not expect the ending to be so strong the way it was. For the first time I said, “Wow, this is very interesting. I want to be a cinematographer. I want to get into the movie business.” That was the first thing in terms of changing my love for photography into wanting to become a cinematographer. I guess it all started back then when I was a child watching my father work in the advertising field.

Was that the episode where the gentleman was being hung and he fantasized the rope broke and he got away?

Yes, the beginning of the episode the noose was around the person’s neck. He was ready to be hung and all of a sudden he escapes and you have the entire episode of him escaping and then at the very end of the short, the film, you come back to the very first shot and there he is with the noose around his neck and he gets hung. So you realize the entire episode took place in his mind as he gets hung in a matter of a split second. That concept really rattled me. I would never forget that. I knew I wanted to take my work as a photographer at the time, as young as I was, that much further. Now you’re dealing with stories and actors and that kind of emotional roller coaster as far as the storyline and the premises. I thought I wanted to become a filmmaker, a cinematographer and that’s how it started.

Many of our readers have an interest in cinematography and pursuing a career in the field themselves. Do you have any advice for aspiring artists?

I get this question asked to me all the time and I have a very simple answer. And I feel very strong about this answer. In order to become a cinematographer, you have to become a photographer first. I suggest young people to carry a still camera on their waist, on their shoulder, around their neck, in their pocket every single day. Whether it’s an iPhone, a pocket camera, a small DSLR that you can put around your neck. When you carry it with you all the time, it’s like having an extra limb on your body. When you start taking pictures every single day, your sensibility starts to shift. It starts to strengthen in terms of your visual sense. You can see the development and growth. It’s not just an innate sensibility. Each one of us can develop it in very personal, unique ways. When you’re taking pictures every day, before you know it you’re starting to take photographs.

So there's a difference between a picture and a photograph?

Everyone takes pictures, and not everyone can take a photograph. The difference is with a photograph, you feel and you imagine the narrative. Whether it’s inside the four lines of your composition or you imagine that narrative outside that box of the composition. There’s a narrative there, there’s an emotion there. It’s not just a quick picture and you press onto the next picture and you’re enjoying the visual aspect of that and you’re pressing on. With a photograph you’re feeling something much more. Your eye is opened much longer before you go onto the next photograph. You’re starting to imagine a story. You’re starting to imagine a narrative of what that particular person is feeling inside of that picture. What’s happening outside of that frame, is there a ride, is there a circus, is there an accident? Is there a love interest? Whatever the narrative may be. Before you know it, your sense of geometry in terms of composing a picture starts to shift. You no longer are standing at a normal height taking these pictures.

You start putting yourself in different vantage points to get the photograph?

All of a sudden you’re climbing on ladders or you’re climbing on top of fences or you’re lying down on your back looking up to give something a little more strength and power. So you’re finding yourself placing in different positions to accentuate the picture that you’ve taken to become a photograph. Your sense of artistic composition starts to shift and change. That’s what a cinematographer does is to take something that’s very normal and bring some sort of life to it whether it’s conscious or unconscious. When I watch film at my leisure or when I’m on an airplane and you’re watching a movie, I watch it without sound. I never watch it hearing the words or hearing the music, which can affect your emotions. I watch it in silence. Being a director of photography is to be able to tell that story visually. When you watch a film in silence, you should be able to know what’s going on and be able to know what that story is about without hearing any words or hearing any music to affect your emotions. It’s a very powerful thing we do as cinematographers because it can be a simple little camera move where someone is standing still and the camera pushes into a close-up of their face. All of a sudden, you’re not conscious of it, but you’re inside that actors head and it draws you in. All of a sudden they could have one little emotion or gesture in their face and you’re pushing in on it. All of a sudden you start to cry – you don’t know why – but you just started to cry for some reason. Your heartstrings just raveled into a knot for some reason. That’s the beauty of what we do as cinematographers and filmmakers is we manipulate the audience’s hearts and emotions that way. It’s a magical art form that we execute.