Talking to Documentarian Randall Wright About Hockney

Filmmaker Randall Wright has documented painters Lucian Freud (Lucian Freud: A Painted Life) and David Hockney (2003’s Secret Knowledge) which Wright made for the BBC. But his latest, Hockney, which opens April 22, is a far more in-depth and personal look at the artist, now 77, known for his sun-drenched California pools and domestic scenes. Hockney gave the director access to his personal archive of photographs and films; along with interviews with friends and art experts, the result is an immersive, revealing study of one of the most important and unique artists of his generation.

David Hockney's "A Bigger Splash." Courtesy Film Movement.

Hockney traces the artist’s roots in working-class Bradford, in Yorkshire, England, where he developed a deep and lasting love for movies, through art school, and to his move in the 1960s to Hollywood, California where in the region’s pools and palm trees he found his lasting subjects. The film examines Hockney’s outsider status, his gayness at a far less open time, and how the AIDS epidemic ravaged his most intimate circle. Now 78, Hockney, with his trademark large glasses and mop of hair, emerges as a hardworking, introspective, witty subject offering insight into not just his own art but what it means to be an artist.

The Credits recently had the following interview with director Randall Wright.

Why did you want to revisit David Hockney after making Secret Knowledge in 2003? What about him or his art did you want to explore in a deeper way?

What is more fascinating than someone who can make great pictures? That’s enough motivation to make a film, which of course is also a picture. David is a glamorous and loveable person, exciting to be with and talk to, but at the same time a much more complex and paradoxical person than he first appears. So, what he does is fascinating, and how his pictures act as evidence for who he is, is fascinating too.

Clearly you had Hockney’s trust and were able to get him to open up. Was that from working on the first film or did you have to earn his trust by spending time with him as you prepared for this one?

I did spend quite a lot of time with him which was a pleasure, and yes I believe we do trust each other, but to make the film was more about making sure it didn’t get the way of what he lives for – making his art.

David Hockney, circa 2007. Courtesy Film Movement.

The archival footage was amazing. Can you talk a bit about how you uncovered it and the condition of the home movies/archival material? Was it all supplied by Hockney or did you have to seek it out?

A lot of it was in the BBC archive and other television network archives, and the rest was in David’s and his brother’s archive. We did spend a lot of time and money transferring it to digital formats at a very high standard and regrading the colors back to what was intended. What I fell in love with in the archive was the consistent wit in David’s various pronouncements, and his incredible clarity of expression.

How long did it take you to make the film? Was David cooperative from the start? You assembled so many interesting friends and art experts; was getting any of them a particular challenge or were they all very willing?

I think they were all very willing. There is a lot of love for David. I did spend a long time finding the witnesses, some of whom had become quite poor and lived obscurely. David was cooperative but the truth is that like many artists, he is so caught up in his current project that he just left me to get on with it.

Hockney in the pool. Courtesy Film Movement.

The film has such a strong sense of place in both Los Angeles and East Yorkshire for Hockney personally and creatively. Can you talk about conveying the importance of both LA and Bradford in Hockney’s life and therefore in the film?

David is essentially an optimist, and playful. ‘The future is exciting’ he says, but at the same time, the need to search, to keep looking at the world afresh, implies a lack of satisfaction with his lot. Having two or more studios always gives him an alternative place to explore or to hide (as Ed Ruscha says ‘LA is a good place to hide’, but that would be equally true of East Yorkshire). So the importance of LA and East Yorkshire is to reveal the core of Hockney’s activity – a constant search, and keeping an open mind, which has produced work which is fundamentally about looking, and which, as I say, is optimistic but tinged with sadness and the feeling of being alone. David makes me aware of the state of being a human being – as we engage with the world, ironically we become overly conscious of ourselves and so paradoxically feel detached. We don’t know whether to follow our heart or our head.

For me the defining quality of Hockney is his never ending energy and desire to keep true to his heart. Despite the problems he has – the love life that fails, the death of his friends from AIDS etc – he is still looking, still deeply committed to experimentation and full of hope.

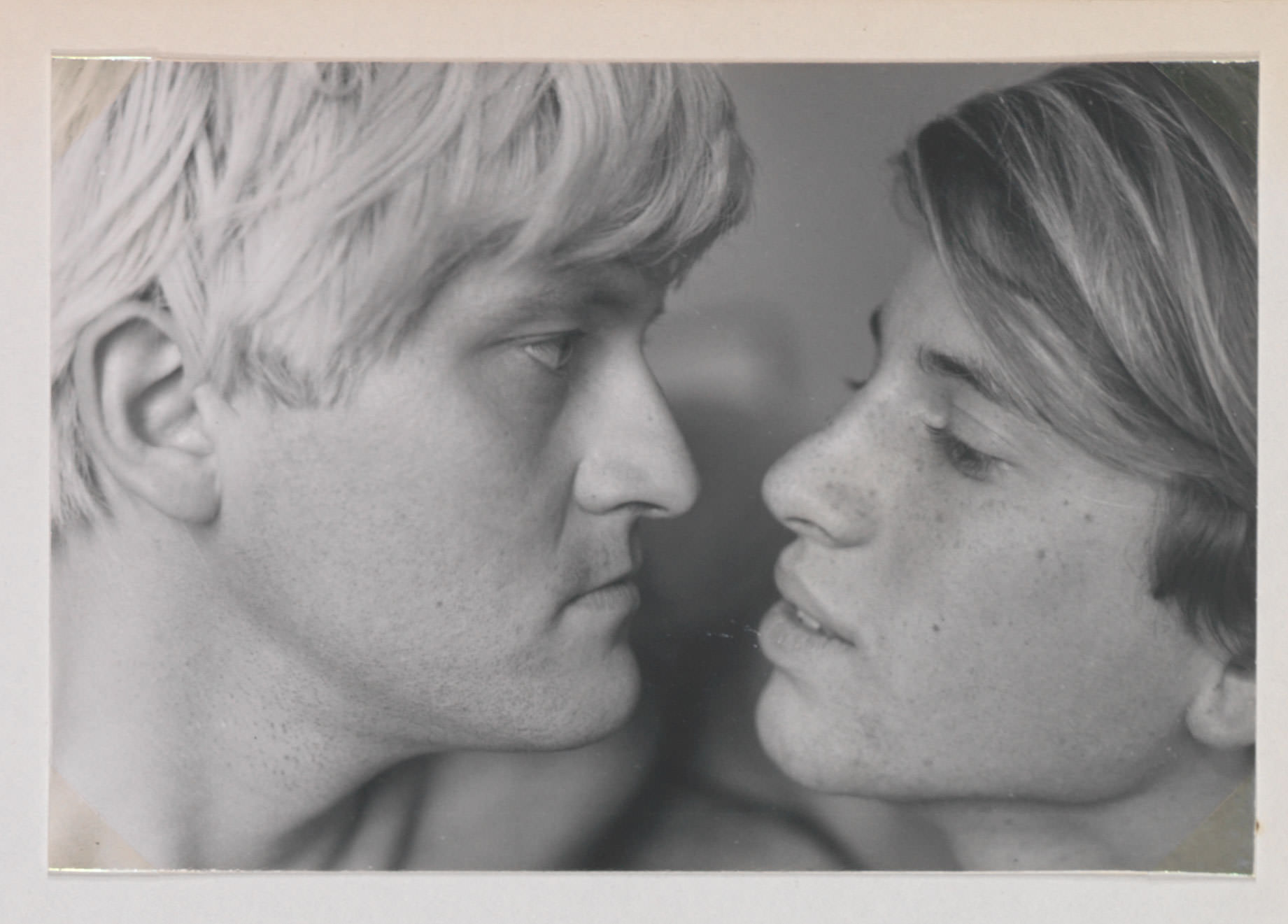

David Hockney and Peter Schlesinger. Courtesy Film Movement.

I really enjoyed David’s stories of going to the “pictures” as a boy and the influence that cinema had on him. Did you consciously try to make a connection between his painting and cinema and how did you try to convey this visually in the documentary?

Well, the whole film is a picture, so a film about painting is already making connections between cinema and painting. What David liked about the cinema was that as a child it was a window on the world – and allowed him to discover the delights of a bright sunshine in Hollywood/ California, which was a contrast with the cold and rain of East Yorkshire. Later of course he saw great beauty in East Yorkshire, but as a boy, cinema was big and thrilling picture of the freedom of America.

Having made a documentary about Lucian Freud and now two on Hockney, I’m interested to know why you are attracted to artists as film subjects and how you approach making a private pursuit (making art) so cinematic?

Fascinating complex characters make good films! Artists often work with their private material but they aim to make pictures transparent to their emotions (or at least romantic artists do). So in a way films about painters have the double benefit of having a fascinating person at the centre and strong visuals. I guess that is why so many films have been made about Van Gogh. I do make films on other subjects too though!

Please tell me a bit about your working relationship with editor Paul Binns who also worked with you on Secret Knowledge. The film flows so seamlessly and the use of David’s artworks is so beautifully presented. It must be a very special collaboration.

Paul is a close friend and hugely talented. We work long hours in the cutting room together, challenging ourselves to tell stories visually and with emotional stepping stones; trying to break the conventions of ‘serious’ documentary, by revealing serious underlying emotions playfully. By amazing coincidence Paul went to the same school as David Hockney, and had some of the same teachers. He and I also love music and work closely with John Harle, another close friend who composes the scores for our films, and like Paul is a big talent. Some sections of the film are carried by music and pictures alone.

Hockney opens in select theaters this Friday.