“Playing the Palace”: A History Of Motion Picture Palaces

Today’s motion picture exhibitors treat the movie going public to the most technologically advanced presentation in the history of the medium. We take a look back to see why this has always been so.

In 1914, Mitchell Mark and his brother Moe, opened what many consider the first movie palace, the one-million dollar Mark Strand Theater in Times Square, New York City. Mitchell Mark hired Samuel “Roxy” Rothafel to manage the theater and bring in the crowds. Earlier in his life, while working as a tavern barkeep in Forest City, PA, “Roxy” organized and managed the tavern’s backroom nickelodeon – a small room with row benches and a white screen tacked to the far wall, in which patrons could watch short movies for a nickel. He ordered films from distributors, advertised screenings in town, set up the benches, cleaned up after screenings, and of course, collected the nickels.

Quick success in the tavern’s backroom led him to try his hand at managing an actual theatre, the Alhambra, in Milwaukee, and success there led him to make his way to New York where he managed first the Regent, and then Mitchell Mark’s Strand. What was Roxy’s managerial secret? He brought to movie theaters such things as uniformed ushers with courtly manners; regal draperies and plush carpeting; soft, colorful lighting in the hallways, lobby and even the theater; orchestral musicians that played musical accompaniment to the silent movies—in short, he made the projection of a motion picture an event that elevated them into the same realm of cultural importance as seeing a production of Shakespeare’s Hamlet or Verdi’s La traviata. Roxy also made sure that on opening night the seats of The Strand were filled not just with the working class that had made the movies so successful in the nickelodeons of the previous twenty years, but also with the upper and middle classes that were lured to the movies by the new upscale amenities, which matched those of the refined cultural events they were already used to. A whole new audience was discovered for an already immensely popular entertainment, and soon other theater owners were following suit.

Roxy followed up his NYC success at The Strand when the owners of the new Rialto Theatre hired him as managing director. This NY movie palace opened in 1916 and included all the amenities found at The Strand plus the introduction of a Wurlitzer pipe organ for movie accompaniment and also for the vaudeville stage shows that now played backup to the more popular motion pictures. The same owners hired Roxy for their next theatre The Rivoli, which opened in 1917. Roxy capped off an extraordinary six year run when he became managing director of NY’s Capitol Theatre. Opened in 1919 as one of the largest movie palaces in the country, with seating for 4,000, the theatre nearly went bankrupt due to poor management, but was saved in 1920 by Roxy when he was brought in and took it over. In 1924 the Capitol was acquired by the Loew’s theater chain, which had just purchased the production companies that would become MGM, and it soon became MGM’s flagship theatre.

With The Capitol Theatre ownership changing hands from an independent exhibitor to an emerging motion picture conglomerate within five years of opening, we see the beginning of the consolidation of the motion picture business at the dawn of the 1920s. By the end of the decade the “Big Five” movie studios – Fox, Warner Brothers, Loew’s/MGM, RKO, and Paramount – had acquired most of the country’s large theatre chains, and dominated the industry by owning the production, processing and distribution of motion picture films.

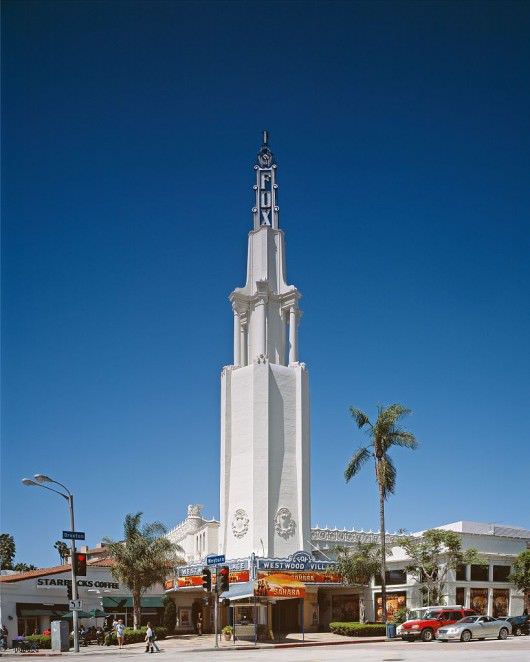

Fox Studios built many incredible movie palaces under its Fox Theatre Chain banner. The Fox Wilshire Theatre in Beverly Hills, designed in 1930 by architect S. Charles Lee in the Art Deco style, today survives as The Saban Theatre. The Fox Village Theatre opened in 1931 in Los Angels, in the Westwood Village development, which was designed in the Mediterranean style. Still open today, it’s known as the Regency Village Theatre, operated by the Regency Theatre chain. It’s striking 170-foot tall, white Spanish Revival tower, on top of which sits an art deco “Fox” sign, is one of the most iconic sights in LA. In the southern U.S., Fox built the breathtaking 4,678-seat Fox Theatre in Atlanta, designed by architect Oliver Vinour in both Islamic and Egyptian architectural styles. Today it’s a performing arts center. The Fox Theatre of Detroit was the studio’s midwestern flagship movie palace, built in 1928 at the dawn of sound films; it was the first theatre to include a speaker system.

Among the glories of the Warner Brothers movie palaces are the Warner Hollywood Theatre, built in 1928 and today known as the Hollywood Pacific Theatre. It seated 2,700 and was one of the few theatres in Hollywood large enough to be converted for the widescreen Cinerama process in 1953. The Warner Grand Theatre opened in San Pedro, Los Angeles in 1931, one of three movie palaces designed for Warner Brothers in Southern California by architect B. Marcus Priteca in the Art Deco style. Today it shows both current and classic films and hosts live performances. The Grand Vision Foundation organizes its continued restoration. Across the country the Warner Bros. Hollywood Theatre opened on Broadway in 1930. It seated 1,600 and was a showcase for the new talkies, which was ushered in by Warner Brothers’s 1927 feature The Jazz Singer starring Al Jolson.

Loew’s Theatre Chain was dominant on the east coast and the Midwest. Founded in 1904 by Marcus Loew as a chain of nickelodeon theaters, it quickly grew, as Loew both bought and built first small theaters, and then large movie palaces. In 1924 he arranged the merger and acquisition of the independent movie production companies Metro Pictures, Goldwyn Pictures, and Louis B. Mayer Productions, forming MGM, so as to provide his theatre empire with product. That same year Loew acquired Roxy’s Capitol Theatre movie palace in New York, making it the MGM flagship. Over the next few years Loew built five flagship movie palaces, dubbed “Loew’s Wonder Theatres,” in the New York City area, all of which screened MGM movies: Loew’s Paradise Theatre in the The Bronx, Valencia Theatre in Queens, Jersey Theatre in Jersey City, and Loew’s King’s Theatre in Brooklyn, all opened in 1929. Loew’s 175th Street Theatre in Manhattan opened in 1930. The King’s Theatre in Brooklyn is set to reopen in 2014 after a complete renovation by ACE Theatrical Group, which will also operate the theatre.

The RKO movie production company was the last to be formed out of a series of mergers in 1928. When the new RKO Radio Pictures absorbed the Keith Albee Orpheum Theatre Chain as part of its merger, it inherited the Hillstreet Theatre in Los Angeles and the pre-eminent vaudeville Palace Theatre in New York City (vaudevillians knew they made it when they “played the Palace”). Both soon became premiere RKO movie theatres.

Paramount Pictures’s New York headquarters is still located at 1501 Broadway in the Times Square district, where it first opened in 1926. The Paramount Building, where founder Adolph Zukor kept an office until his death in 1976, housed The Paramount Theatre, a 3,600 seat movie palace and the studio’s flagship theatre, which exhibited films through 1964, when the theatre was converted into more office space. On the west coast Paramount took control in 1929 of Grauman’s Metropolitan in LA, which had opened in 1923, and also built in 1931 the luxurious art deco Paramount Theatre in Oakland, CA, seating 3,000. Still open today, it presents live dramatic and music events, and exhibits classic Hollywood films.

Strong willed independent exhibitors would not be left behind, nor swallowed up by the majors. Two of the most famous were Samuel “Roxy” Rothafel in New York and Sid Grauman in Los Angeles. “Roxy” was finally able to open his own movie palace in 1927, calling it, aptly, The Roxy. Seating 5,900, it was billed as “the cathedral of the motion picture,” and its amenities included a rising orchestra pit for its permanent 110-member symphony orchestra, a Kimball theatre pipe organ, and a projection booth recessed into the rear of the balcony rather than higher up behind the rear wall, which cut down on soft focus due to steep angle projection. Thus Roxy’s Theatre had the sharpest picture in town. To round out the extras, it also had a male chorus, a ballet company, and a line of precision female dancers called The “Roxyettes.” Later, when Roxy moved on to help open The Radio City Music Hall in 1932 with owners John D. Rockefeller and RCA (which helped create, and had a stake in, RKO Radio Pictures) the “Roxyettes” went along and were redubbed the Radio City Music Hall Rockettes.

West Coast theatre impresario Sid Grauman created three of the greatest movie palaces in the world, all of which are today still in operation. Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre opened in Hollywood in 1922, seating 1,770. It included an Egyptian courtyard, which patrons walked through to enter the theatre, and ornate Egyptian inspired interior designs. Its success inspired the subsequent creation of up to 100 Egyptian style movie palaces around the country in the years following Grauman’s original. Today The American Cinemateque owns and operates the original Grauman’s Egyptian, having split it into two theaters. Grauman next opened The El Capitan Theatre in Hollywood in 1926, as a dramatic theatre. It presented plays through the late 1930s, when the Great Depression caused it to scale back to the comparatively less expensive business of movie exhibition. It’s independence from the studio theatre chains in the early 1940s allowed it to screen the world premiere of RKO’s controversial Citizen Kane in 1941, after director Orson Welles could not secure a willing studio theatre owner to present it. Today the El Capitan is owned and operated by The Walt Disney Company. In 1927 Grauman opened his Chinese Theatre on Hollywood Blvd in Hollywood, CA, which today is still one of Tinseltown’s richest and most enduring symbols. Designed by the architectural firm of Meyer & Holler, who had also designed Grauman’s Egyptian, the exterior resembles a Chinese pagoda. Just as renowned as the theatre are the concrete blocks in the forecourt, which contain 200 handprints, footprints, and autographs of Hollywood legends.

With the forced separation of the Hollywood studios from their theatrical exhibition businesses due to a 1948 U.S. Supreme Court ruling, plus the growth of television in post WWII America, both the studios and these newly independent theatre chains struggled through the 1950s and 1960s.

The economics of operating single screen movie theaters and movie palaces hit home in the 1960s with the continued influence of TV. Theater owners like AMC’s (for American Multi-Cinema) new president Stanley Durwood, realized they could double their revenue by building and operating two theaters while keeping the same size staff –hence the “multiplex” grew out of new management concepts and greater organizational and economic discipline. Durwood’s AMC opened the two screen Parkway Twin in a shopping mall in Kansas City Missouri in 1963. In 1966 AMC opened a four-screen theatre, and in 1969 it opened a six-screen theatre. Continued expansion of this new business model led AMC to open the first North American “megaplex,” a twenty-four-screen theatre, in Dallas in 1995. Other chains followed suit.

Today AMC Theaters with 339 North American locations sits behind Regal Entertainment Group, with 540 locations, and ahead of Cinemark Theatres, with 298 U.S. locations. All provide top of the line theatrical motion picture exhibition, with plush stadium style seating, multiple concession stands, continued conversion to all digital 4K projection, and ever higher quality sound systems. Once again as at the beginning of the last century, the world seems wide open for an exciting future.

Featured Image: Roxy Theatre New York, courtesy the Library of Congress