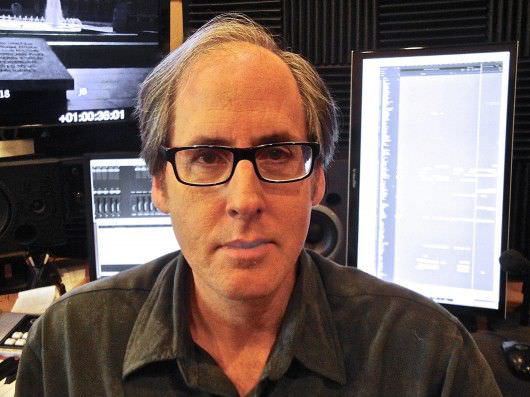

House of Sound: Composer Jeff Beal Talks David Fincher, Scoring Netflix’s Breakout Hit, and Jazz

When composer Jeff Beal heard that director David Fincher was involved in an intriguing television project with Netflix, he wanted in. That project was House of Cards, an original series starring Kevin Spacey as House Majority Whip Frank Underwood, a vengeful political animal with scores to settle. Fincher asked Beal to submit some musical sketches, and what Beal created ended up becoming the basis for the show’s theme, and Beal himself became the show’s composer, with the two-disc score of his album available on April 9 on Varèse Sarabande Records (we’ve embedded it for your listening pleasure below).

Cards, which debuted in February, is Netflix’s first original series and was instantly the talk of the entertainment industry. Releasing all 13 of season one’s episodes simultaneously, Netflix was essentially turning the TV production model on its head. There was a lot of talk about what it meant for the future of the television industry, and as valid and interesting as those questions are, we were just as curious about what the all-at-once delivery method meant for creatives and audiences alike. Beal expounds on this below.

Beal’s work has earned him awards and the respect of peers in the film world such as the aforementioned Fincher, Al Pacino (he scored Pacino’s Wild Salome, in 2011) Ed Harris (he scored Harris’s Pollock) and a slew of independent directors and documentarians (he scored three films that premiered at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, Blackfish, The Battle of amfAR, and When I Walk.) Beal’s work in TV includes HBO’s Rome and Carnivále, and ABC’s Ugly Betty.

We spoke to Beal about Fincher’s ‘composer-friendly’ method of working, why documentaries are a composer’s dream, and how literacy in jazz is a film composers secret weapon.

The Credits: How’d you get involved with House of Cards?

Beal: I knew David Fincher, we’d actually done a Super Bowl commercial together [you can read about Fincher’s ad work here, the spot he and Beal did was for Motorola], about five years ago, and it was also around the time I was finishing working on Rome for HBO. When I saw the press release for this new project he was working on, I was very intrigued, so I reached out to him about it. We met last year around this time, and before he started shooting the first two episodes, we talked about concepts and ideas for the music. And because of the way he works, he actually asked me to create some sketches for him before he started shooting. Which was fun for me, because I knew from his previous work with Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross that he liked to work that way sometimes. He’ll take materials from them and use them in his editing process, or even in his shooting process.

Tell us about working on the score before the show was actually shot, which is not the typical way it works.

Aside from just loving David’s work, I think the way he uses music in his films is always so smart, and he really understands the power of music. And I was intrigued by the opportunity, being a more traditional model type composer, who usually always writes to picture. I loved the idea of writing music before it was shot. I got about four scripts to work off of, and David’s notes, and that’s how I started. I think one of the things that working that way does for you as a composer is it gets you out of the tyranny of a scene, where you go, ‘Okay, I’ve got a minute and a half, and this happens, that happens, I’ve got to connect these dots,’ it tends to drive the compositional process in a certain way, whereas when you’re just writing a pure musical idea or theme, you’re sort of free in a way to imagine and conceptualize. Out of that first batch of pieces I sent him, three of those became major themes in the score, one of which became the main title of the show.

What kind of sound was Fincher looking for?

When David and I first met he shared with me one piece by this band Supertramp called ‘Crime of the Century.’ It’s something I really didn’t know that well, but the end of it has this sort of vamping sound, this really strange mixture of classicism and something much grittier. And I think that’s what spoke to him. What we tried to do is create this sense of the political underworld with more electronic sounds and definitely the bass, which became one of the most important sounds for Frank’s character. It had this predatory energy, which was really good for his character.

There’s also a lot of piano and electronic music in the score, too.

We also had the ambient electronic part of the palate, but then on top of that we had piano, which serves multiple purposes dramatically. It can be emotional, it can be reflective, it can be noir-ish, but it can also be precise and very intellectual and smart in a more minimalist rhythmic way. And then I’d say the third major element was the string orchestra, which I used throughout the show, I had a group of about seventeen players and the strings gave a connective element to the score. It was able to play size and play mood and also play the world of Washington.

Was there any difference for you as a composer to work on House of Cards because of the way it was released all at once?

You’re always thinking about your audience, and we had a sense in which once you finish an episode, they might just push play and go right into the next one. So I would say, creatively, it was much more like scoring a really long movie. It was similar to the kind of experience I had doing HBO’s Rome and Carnivále, where the scripting was very linear and operatic. This was especially fascinating because the source material was so unique. Another aspect was there was virtually no temp music used in the show, so for me that was an incredibly liberating process. There have been a few projects that I’ve done that didn’t use any temp music, like Pollock, which I scored for Ed Harris. I always think of those projects, where I didn’t have the extra ‘paint-by-numbers’ template laid down for me, as incredibly liberating and fun.

So is temp music the composer’s enemy?

It’s a good tool. Editors often use it, for example; they’ll cut their films with temp music from other movies. Part of the reason why temp music is used is that early cuts need to be sent to a studio, and you don’t want to send something to a studio without any music in it, because a lot of times they’ll think, ‘this is crap!’ [Laughs] Whereas if you have some temp music, it’s a crude way of showing the dramatic arc and the tempo of a scene, and those are all great things. The danger of temp music, though, is that it becomes a straight jacket…you get used to it, once you’ve heard music in a situation, there’s a typical syndrome called ‘temp love,’ which is when a certain piece of temp music fits so well that no matter what you write, you can’t better it. So it can create a same-ness, and certain famous scores have been over-temped, over emulated, so they percolate and create a regurgitated feel in scoring, which is very much against my personal aesthetic.

You’ve done a lot of documentaries recently, from 2012’s critically acclaimed The Queen of Versailles to four that are coming out this year. Has that been a conscious decision?

I tend to try to tell young composers it’s not just about getting a job, but getting the right job, and finding things that have the right fit for you. And for some reason, I think I’ve had a lot of success and creative ‘fits’ doing documentaries. For composers, docs are wonderful because directors and viewers are embracing the idea of music as a character in a documentary. I think compositionally, the role of the score in a documentary is usually huge, because you don’t have a lot of the artifice of scripted performances—a lot of times documentary scores have a much bigger role to play in a sense in terms of telling the story, which I particularly enjoy.

You come from a jazz background playing the trumpet—how has that informed your work in film and TV composing?

It’s funny, when I look at a lot of my colleagues from my generation, like Mark Isham, and also John Williams and Jerry Goldsmith—all of them started in jazz, as well as one of my favorite concert composers, John Adams. Jazz is almost a required literacy in terms of being a composer today. It gives you a facility and ability to conceptualize music in a way you can’t get in any other discipline. As I got more and more film projects I realized that I was sort of transferring the same skills I was using when I was improvising with the band. It’s not just about what you’re doing—playing jazz is very much about listening to what everybody else is doing. And that’s very much what I love about being a film composer, it’s intensely collaborative, it’s reactive…it’s about how what you’re doing is amplifying what somebody else is doing, like the actor or the screenwriter or the director.

You’re now the fourth composer we’ve talked to in our composer series. John Debney, John Ottman, and Christopher Lennertz all had a lot to say about the effect of film piracy on composers, and, ultimately, on the entire film industry. Your thoughts?

It’s a huge problem. We have a teenager and there’s an educational gap when it comes to infringing on copyright and intellectual property–unfortunately the Internet created a sense in which doing that was okay. I think there’s an interesting generational shift, and I actually think companies have a responsibility to educate and provide ways for people to obtain things that is easier than stealing it. And I think we’re actually getting there, I’m more optimistic than I was maybe a couple of years ago. One of the things I’ve found in my dealing with fans that want music is that most people want to pay, they’re happy to pay for something. I think we’re still looking for the model in film that’s going to do that. Netflix is actually on the cusp of that. For a very small fee you can have access to a huge library of content. I think as companies innovate and expand their ability to reach consumers and make it easy and enjoyable for them, hopefully that tide will turn.

What would you tell aspiring composers?

Persistence. Just the ability to persevere is half the battle. But I’d also encourage young composers to, aside from studying music, really study film. One of the things that’s important to understand as a film composer is that film is really a form of literature, and the better you can grasp the vocabulary of film, the history of film, and just the way filmmaking is done, the better you’ll be equipped to dive in.

Featured Image: Kevin Spacey and Robin Wright as Frank and Claire Underwood in 'House of Cards.' Photo Courtesy Netflix.