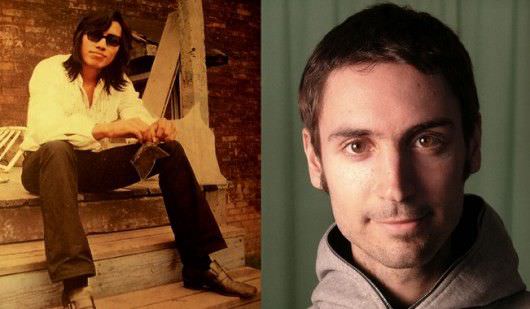

Talking With Malik Bendjelloul, Director of Oscar Nominated Documentary Searching for Sugar Man

A surprise hit at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival, where it won both the Audience Award and a Special Jury Prize for Best International Documentary, first time filmmaker Malik Bendjelloul’s Searching for Sugar Man opened last summer to strong critical reviews and robust commercial success. The story of singer-songwriter Rodriguez, from his late 1960s emergence from the streets of Detroit; his startling and strange success in South Africa during the waning days of Apartheid in the 70s and 80s; his sudden disappearance from the music scene; and his startling re-appearance in the mid 90’s, this story is definitely stranger than fiction. We spoke with director Bendjelloul about how he first learned of Rodriguez’s story, the long struggle to make the movie, his relationship with Rodriguez, and the film’s Oscar nomination for Best Documentary.

The Credits: How did you learn about Rodriguez’s story?

MB: I was working for Swedish National Television for a number of years, doing 60 Minutes type of stories—short stories about spectacular subjects—traveling around a lot. After a while I thought the travel was the most fun aspect of the job. I wanted to travel for a longer time, so I quit my job and bought this really cheap around-the-world ticket. I flew to sixteen countries with a bad camera of my ex-girlfriend’s, looking for stories. And this [story of Rodriguez] was one of the six stories that I found on that trip in 2006.

In the film, the audience first learns of Rodriguez’s story from Stephen Segerman, the record shop owner in Cape Town, South Africa. Is that how you first heard the story?

No. Before I went on that trip I was sitting reading articles from the places I knew I was going to visit. I found six stories in different newspapers and this was one of those six stories. It sounded remarkable.

When you decided you wanted to focus on this story, how did you go about starting to film?

I started in 2006, using that bad camera of my ex-girlfriend’s, that I couldn’t really use in the real film, and I met Stephen, and I met Eva [Rodriguez’s daughter, who lives now in South Africa]. And then it took another two years until I started with the actual film, for real. Already in 2006, Eva said “Malik, don’t you think this could be a longer movie?” And I said, “Yeah, maybe you’re right.” And that’s kind of where the idea started to make a longer film about it [rather than a short news story]. Then in 2008 I started to do the [longer] film for real, and I started meeting all the other people, I met Craig [Craig Bartholomew Strydom, a music journalist] in South Africa, and then I went to America and I met the producers [of Rodriguez’s 1970 debut album Cold Fact, Dennis Coffey and Mike Theodore], and then Rodriguez was almost the last one I met. He hadn’t promised to be in the movie. He just said we could meet and chat, and we can see what’s going to happen, but he said he probably was not going to be in the movie, because he doesn’t like cameras. And I already knew that – his daughter told me he was not going to be in the movie.

So over time you were able to convince him?

Yeah, but again—very, very slowly. But the first time we met we didn’t do any interviews, and the second time we met, because we kind of became friends, was actually in Sweden, he came and visited me at my home, and then the third time, back in Detroit, that’s where you see that interview by the window that’s in the movie.

When we first see Rodriguez as he is now, the camera is outside on the street in front of his home, and you have him open a window and lean outside it, that’s such a wonderful reveal. Did you think ahead of time that was the way you were going to introduce him?

Yeah, when I first met him, I said to him, “Rodriguez, to be able to make this movie we have to do some kind of trailer, and I think the last shot of the trailer is going to be you opening a window, to give it some kind of hope for the future.” And he said, “Yeah I can do that, I don’t really need to talk if I do that. Ok, I can open a window.” And it was for the trailer but it wasn’t supposed to be in the film. I didn’t know how to use that in the film, but then it worked.

When you were shooting did you already have the idea of how you were going to structure it, starting as a mystery story?

Well that’s the way I heard the story from Stephen, and the article I first found was also Stephen’s story. From the very beginning I knew I was going to tell it from the South African perspective of these two fans [Stephen and Craig] and how they wanted to find out what happened to this musician, who they thought was dead, and then they find him alive! It was incredible.

On the short “making of” documentary on the Blu-Ray, there is an outtake from your film, of Steve Rowland’s [the producer of Rodriguez’s second album, 1971’s Coming From Reality] surprise upon learning of Rodriguez’s subsequent success in South Africa from the mid 1970s onwards. Did Rowland and others in the US not realize the big success Rodriguez was having over there?

He didn’t actually know anything about Rodriguez’s South African success, I told him about that, he had no clue about that. And their love for Rodriguez is real; they really do think he is the greatest artist ever.

How do you feel about being nominated for an Oscar for Best Feature Documentary?

It’s awesome, it’s crazy, and it’s fantastic. It’s surreal, to have the word “Oscar” associated with yourself, it’s just ridiculous!